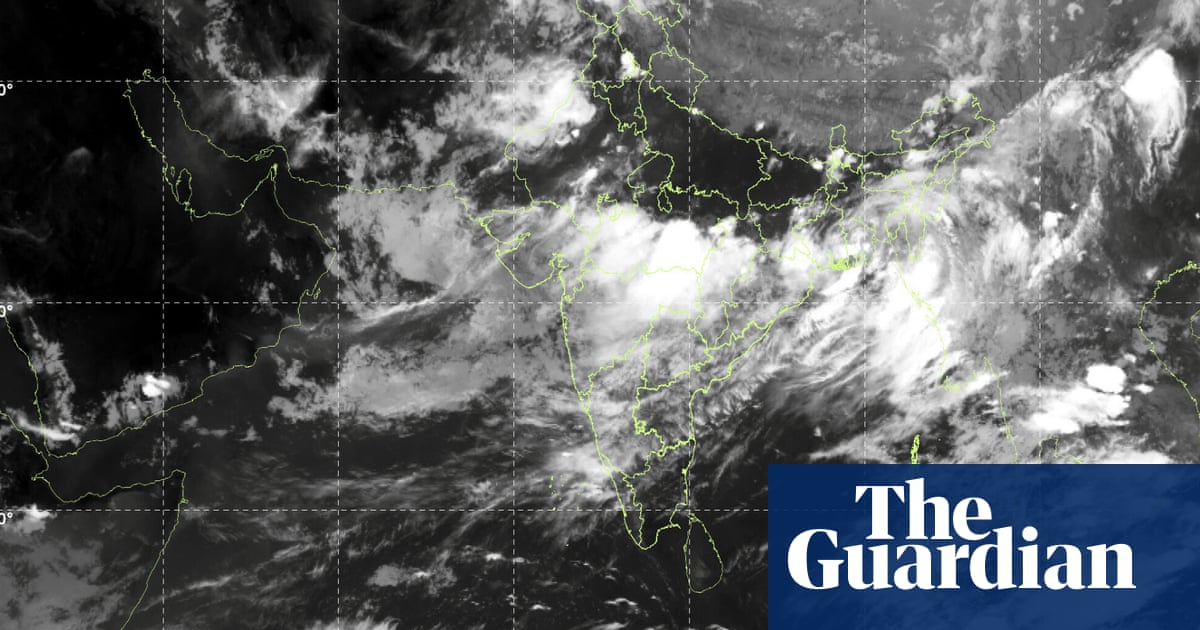

Most people in Brisbane were battening down the hatches ahead of the arrival of Tropical Cyclone Alfred. For a few, though, it was one of the most exciting natural events of their lives.

Over the course of the weekend and into Monday, throngs of birdwatchers lined the shores of Bramble Bay in the bayside suburbs of Shorncliffe, Sandgate and Redcliffe, telescopes and cameras at the ready.

But the excitement of seeing birds that usually spend their lives at sea up close as they were pushed up against the coast – some flopping into suburban back yards, barely able to walk – was tempered by sadness and pity.

While seabirds are highly evolved to survive in extreme environments, cyclones cause mass casualties.

Unable to land or find food in the churning ocean, they become exhausted and quickly lose conditioning. Many are carried hundreds of kilometres inland, where they invariably perish. The lucky ones are found and taken into care.

For Twinnies Pelican And Seabird Rescue, a bird rescue charity run by identical twins Paula and Bridgette Powers, the weeks after a cyclone are hectic, with dozens of birds transferred to their rehabilitation centre in Landsborough on the Sunshine Coast.

“I’m so glad we never got hit like Brisbane and the Gold Coast, but we were worried about these seabirds out there copping it,” they say.

A conversation with the twins is a unique experience. They don’t just finish each other’s sentences; they speak in unison and in stereo. But they are united by a love of all creatures great and small.

They tend to a masked booby, a gannet-like bird lucky to survive the night. It’s in a bad way, waterlogged, shivering and infested with bird lice. At one point, it rocks back and forth.

“His waterproofing is not the best,” they say. “When they come in not waterproof, it takes a while to get them ready for release.”

Seabirds have an oil gland at the base of their tail, which they first rub their heads against, then over their feathers for waterproofing. As their condition deteriorates, they lack the energy to administer this routine self-care.

Its prospects look grim. “It’s a bit too early at the moment to say, because he’s so exhausted anything can happen,” the twins say. “Their little hearts can just give in. But at least he’s in a nice warm bed, not in the ocean. We’ll give it our all, won’t we darling?”

A pelican – recovered after being pushed up against the rocks at Golden beach, Caloundra – is looking better, despite suffering from botulism. “It can be caused by many things, like a carcass in the water, but all this rain stirs up everything,” they say.

“He’s been standing and sitting, which is a good sign. His eyes are a lot more moist – they were really dry and closed when he was brought in.”

Prof Richard Fuller, from the School of the Environment at the University of Queensland, says such storms are “incredibly disruptive”.

after newsletter promotion

“Suddenly these birds are on a coastline with which they have no familiarity or real concept of what to do, their usual food sources are gone and the weather conditions are atrocious. So it’s really kind of a perfect storm,” he says – no pun intended, of course.

But, he says, such events also present a rare opportunity. “Many seabirds are declining dramatically all around the world. We’ve noticed that here in Australia too, so these events give us an insight into what’s happening out there in the ocean, and gathering that information is really useful.

“To track seabird populations we need to monitor them, and that’s usually done at breeding colonies, but this gives us a window into what’s happening at sea when birds are away from their nesting areas.

“We had a shy albatross, for example, which is incredibly rare in this part of the world; this record shows that there are still some of those birds here.”

Some are even rarer. At least two Leach’s storm petrels were photographed over the weekend – a species recorded only once previously in Queensland, with fewer than 10 confirmed nationwide.

“Storms of course are natural events, and mass mortality during storms is part of the biology of seabirds,” Fuller says. “It’s a massive event, so a lot of birders were awestruck by what was happening.”

For 23-year-old Kye Turnbull, it was a lifetime thrill. He spent the entire weekend at Bramble Bay standing in the teeth of the gale, prompting one online friend to inquire jokingly whether he required food drops.

“It’s the most awesome birding event I’ve ever experienced,” he says. “After [Tropical Cyclone] Oswald in 2013 – which I missed out on for being too young, I’ve been waiting for this to happen, and it’s finally happened. Yesterday was probably the best birding experience ever for me.”

For some it was an expensive experience too, as their equipment was buffeted by wind and torrential rain. “I saw quite a few cameras die yesterday.”

3 months ago

34

3 months ago

34