As you enter the galleries you can’t avoid the slobbish giant. Maybe it is drunk or drugged as it towers and slumps, a red and brown creature with a demonic face and sagging stomach. If the cord suspending it from the ceiling snapped it would just be a pile of hemp on the floor.

This monster has all the qualities that make the art of Mrinalini Mukherjee, who was born in Mumbai in 1949 and died in 2015, funny, fascinating and surreal. She created it in 1985, making it, like many of her works, with tightly woven, intensely coloured natural fibres. It is called Pakshi, meaning bird, and now I see it, the feathery flanks and floppy wings. Mukherjee’s sculpture is a hallucinatory but sharply observed response to nature, full of echoes of the Indian landscape and, in this case, India’s skies. If a bird can become an ogre in her fantastic imagination, a flower can grow into a fat, sprawling, bloodied excrescence and a tree transmute into gold. So why does the Royal Academy try to suffocate her exhilarating works in an incoherent show that surrounds them with mediocre stuff by much less interesting artists?

The grand title is A Story of South Asian Art, but no story is told here that excites or even makes sense. A simple, traditional retrospective – artist is born, starts career, work develops – would give you a nice linear framework but oh no, that would be too simple. Instead this meander “traces a century of south Asian art” as the wall text at the entrance says, setting Mukherjee within a “constellation of mentors, friends and family”. But why? Any gain is negligible compared with the loss of energy and urgency.

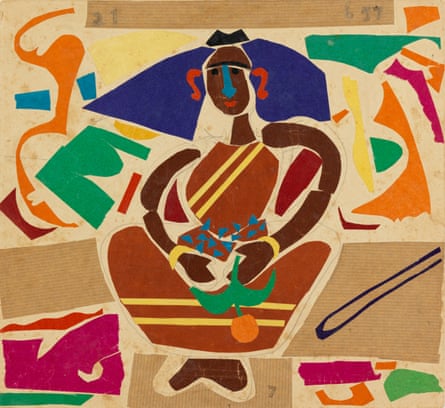

It starts out nicely enough. Mukherjee’s parents were artists and her father Benode Behari Mukherjee struggled with visual impairment, eventually becoming blind. Maybe that is why his Matisse-like collages are so electrically bright, loving colour like it’s life. But if you want to pursue this idea of exploring Mrinalini Mukherjee’s affinities, she seems to have got her gift for sculpture from her mother Leela, whose carved wooden figures have a chunky totemic energy.

Of course context is important, but why not go deeper? Mrinalini Mukherjee’s sculpture has ancient and marvellous, and clearly self-aware, roots in Indian art – or south Asian art as is pedantically insisted on here – with its history of natural observation, hooded cobras, elephant-headed gods, dancing bodies and abstract freedom, most mysteriously in the representation of Shiva as a cylindrical lingam. Mrinalini Mukherjee’s woven hemp sculpture Adi Pushp II reminded me of a lingam, probably because they both take inspiration from the stamen of a flower. This sculpture, whose title means “First Flower”, is a grossly shaped, triffidian plant that blossoms with erotic suggestiveness. It’s consciously, smartly rooted in India’s religions and art and leaves all the other artists in the deep shade it casts.

This is how it goes. At first, the inclusion of Mrinalini Mukherjee’s friends and family sort of sets her early development in context. But as soon as you see her sculptures from the 1980s onwards you just want to see more of them and less, and soon none, of the watercolours by her “circle” that clog up the gallery like slow traffic. It’s as if she is forced to make endlessly polite chit-chat about what everyone else is doing.

Her art is international, not local. Given her rise to brilliance in the 80s, it’s tempting to see her as a magic realist. She mingles modern India’s history with surrealism, dreams and fantastical images of an intense national landscape. From this she produces an enchanted, bubbling cocktail of birds and flowers, gods and monsters infused with desire and dread. Night Bloom II, which is owned by the British Museum, has the shape of someone sitting in the lotus position, yet it is another festering flower of the mind, made of sloppy, sliding green ceramic, some of it glazed blood red.

The wall text says the figure looks female, but to me it evokes statues of seated Buddhas and sages that are beyond gender. It is full of contradictions, both spiritually calm and sensually violent, possessing the tension that makes a work of art not just impressive but enduring.

Mrinalini Mukherjee’s art drew deeply on her culture but transcended the local. It is as meaningful now as in her lifetime, and accessible to everyone. What’s so bad about that? Banging contemporary art is banging contemporary art – but no, this exhibition keeps throwing a wet blanket over it. Here’s another so-so landscape painting, another tedious figurative screen.

How clever of the Royal Academy to give this great modern artist a show. How stupid to muffle her in second-rate surroundings. I suspect she knew exactly how much better she was than her family and friends.

-

A Story of South Asian Art: Mrinalini Mukherjee and her Circle is at the Royal Academy, London, 31 October to 24 February

3 months ago

51

3 months ago

51