His luminous colours and sensual brushwork adorn countless mugs, posters and tote bags as well as blockbuster exhibitions. But the commodification of Pierre-Auguste Renoir and his fellow impressionist painters has been missing something.

Renoir was an accomplished draftsman who produced a distinguished but largely unheralded collection of drawings, pastels, watercolours and prints.

More than a hundred of these works are now on display in a new show, Renoir Drawings, at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York. Tracing the entire arc of the artist’s life and career, it is the first exhibition in more than 100 years devoted entirely to Renoir’s works on paper.

“Because they are works on paper, they are not exhibited permanently in any institution,” says Colin Bailey, director of the Morgan and curator of the show. “Having access to watercolours and pastels and red chalk and white chalk expands your knowledge of the artist. While these will seem very Renoir-esque, they will be less familiar.

“Also, because we are showing his work decade by decade, you get a real sense of how he develops and the different stylistic moments in his career.”

Born in Limoges in south-western France in 1841, Renoir grew up in Paris and began his career decorating porcelain. He fell under the influence of Gustave Courbet and met fellow artists such as Claude Monet and Alfred Sisley – figures who would later help define impressionism. By 1869, Renoir was painting alongside Monet on the banks of the Seine, experimenting with a brighter palette and a lighter touch that hinted at the new style to come.

The oil painting La Loge (The Theatre Box), shown at the first impressionist group exhibition in Paris in 1874, and Luncheon of the Boating Party (1880-81) have become star attractions of the Courtauld Institute of Art in London and the Phillips Collection in Washington, respectively.

Bailey, one of the world’s leading Renoir scholars, says: “It was a struggle at the beginning. They all had a language that now is so beloved and familiar but it was initially highly transgressive: the high tone, the visible brushwork, even the subject matter from contemporary life.

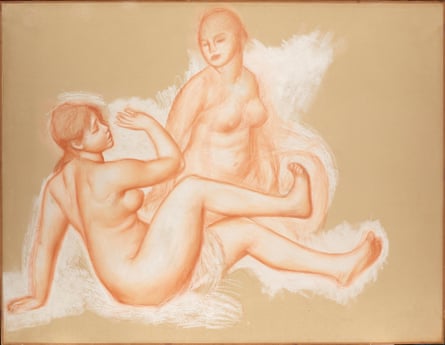

“At the same time we see in the show, after he’s able to travel to Italy and returns in the 1880s, he becomes less interested in Parisian social life, more interested in the female nude, where he is undoubtedly one of the great exponents, and this comforting world of young women, of families, his own family, where it’s a very Arcadian image of a world detached from the struggles of urban life. That is one of the reasons why he is so appealing to an audience.”

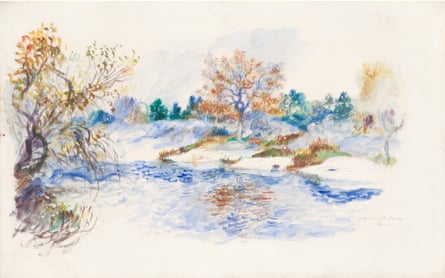

But works on paper lie at the heart of his artistic practice, influencing the paintings for which he is best known. Renoir Drawings, presented in collaboration with the Musée d’Orsay in Paris – where the exhibition will travel next year – brings together early anatomical sketches, lively glimpses of Parisian and rural life, refined pastel portraits of his circle and illustrations made for literary works such as Émile Zola’s L’Assommoir.

Bailey explains: “As the show developed, we were trying to both represent the range of his works on paper in different media – not only pencil and crayon, but also pastel and watercolour – then also to try and do this as a chronological survey, from the early few academic drawings as a student to the late works, and then finally to make constellations around certain major pictures for which preparatory and related drawings exist.”

At its core, the exhibition explores a pivotal moment in Renoir’s career – his renewed engagement with preparatory drawing – when he developed extensive series of studies that laid the groundwork for his ambitious, large-scale compositions. Dance in the Country (1883) and The Great Bathers (1886-87) are featured alongside their related sketches and figure studies, providing a rare chance to see painting and preparatory material reunited.

Indeed, this is the first time the painting The Great Bathers will be shown in New York. Its loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art was made possible by a recent change in lending restrictions.

Bailey says: “Until now, if you wanted to study the gestation and the growth and the genesis of that large, important and beautiful painting, you had to go to Philadelphia. This is extremely generous of the Philadelphia museum. But it’s now lucky for us that a change of restrictions has allowed us to bring all of the large drawings around The Great Bathers, including the drawing that was given to us in 2018.”

It was The Great Bathers that proved the catalyst for the show. In 2018, when the Morgan trustee Drue Heinz died aged 103, the museum was invited to choose a work from her collection. It selected Renoir’s monumental red-and-white chalk preparatory drawing for The Great Bathers. “Her estate was very happy for us to have this and this spurred the possibility of doing a full-scale retrospective of his works on paper,” Bailey says.

Among other standout works in Renoir Drawings are delicate pastel portraits such as Portrait of a Girl (Elisabeth Maître) (1879), borrowed from Vienna’s Albertina museum. There are also intimate late-period studies of Renoir’s wife, Aline, and their young sons, capturing familial warmth with characteristic sensitivity.

For Bailey, mounting his first exhibition as a curator since becoming director 10 years ago, a personal favourite is Renoir’s pastel portrait of his friend and fellow artist Paul Cézanne. He says: “With Cézanne, he’s deeply connected from the beginning. Renoir travels to L’Estaque to work with Cézanne. He admires him.

“He and [Edgar] Degas are very good friends as well, except at one point because Renoir sells a pastel that had been given to him by Degas because he’s in need of some money. Degas is so angry that he returns a Renoir to Renoir and they don’t speak for a couple of years. These artists are very close in the late 1860s and 1870s and some of them remain close throughout their careers.”

The exhibition concludes with the plaster sculpture The Judgement of Paris (1914), created in collaboration with sculptor Richard Guino after arthritis severely limited Renoir’s use of his hands, which he was forced to bandage. For Bailey, it is a demonstration of Renoir’s resilience and resourcefulness.

“Arthritis doesn’t stop him from painting ambitious large nudes and landscapes and the mastery in some of these late drawings is complete. In a way, like Monet’s cataracts and Degas’s blindness, artists have a sort of muscle memory and they can continue to create.

“In Renoir’s case, he certainly couldn’t model plaster or marble but through his designs and his guidance for Guino, he was able to create very beautiful sculpture. We have a suite of drawings that relate both to the sculpture and the painting that is also part of that series. In some ways drawing for him almost transcends media at the end. He can work in sculpture, he can work in paint, he can work in chalks and it’s the same world.”

The last comprehensive exhibition devoted to Renoir’s drawings was at the Galerie Durand-Ruel in Paris in 1921. Bailey believes there will be much to learn. “Drawings help you see the germ of ideas,” he says. “They also help you see the artist at work and because they’re fragile, because they’re either in museum storage or in private collections, they’re not constantly visible.

“I’m hoping that this chance will amplify people’s understanding of Renoir’s productivity and they will see what an interesting and accomplished artist he is in different media on paper, not just charcoal but also these beautiful watercolours that will come as a surprise to people because they seem like very much like Matisse and Bonnard before their time.”

-

Renoir Drawings is on display at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York until 8 February

3 months ago

74

3 months ago

74