The future of the youth minimum wage will come under review as part of a major inquiry into rising inactivity among Britain’s young people by the former health secretary Alan Milburn.

The social mobility expert said that unless the government tackled some “uncomfortable truths” about the labour market there was a risk of creating a “lost generation” of young people.

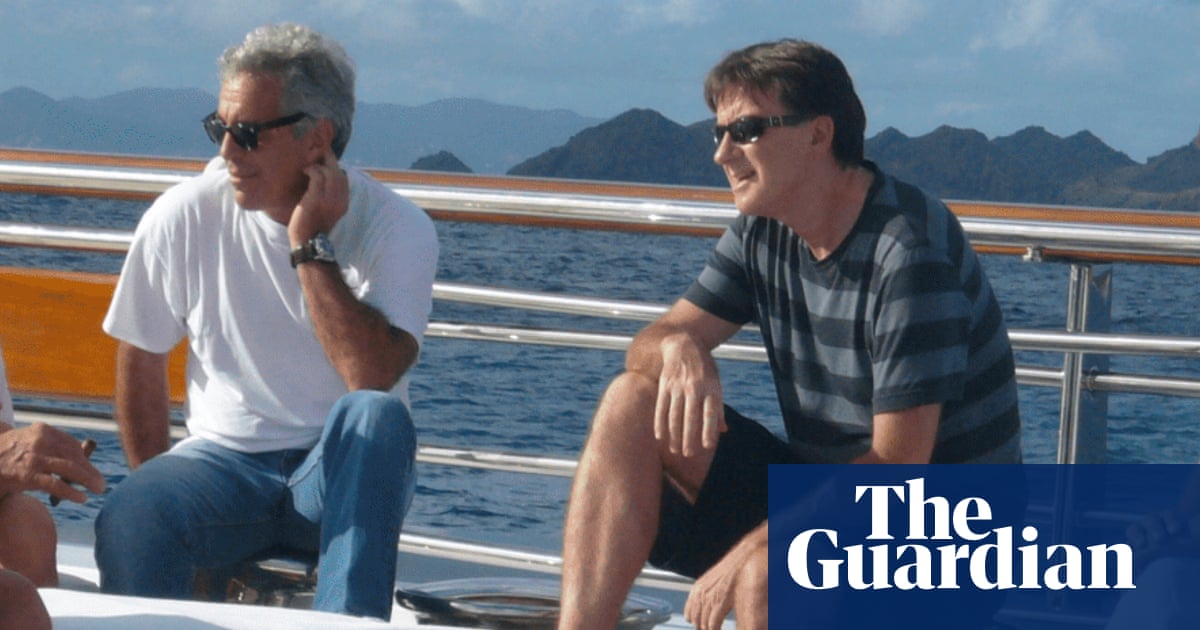

In an interview with the Guardian, he said the rising overall welfare bill was “unsustainable fiscally and economically” but insisted that any reform of the system had to focus on righting social injustices first.

Milburn’s intervention over the minimum wage echoes recent warnings from economists that the increase in youth rates – which the government is trying to equalise with the adult rate – could lead to some being “priced out” of entry-level jobs.

But it is likely to be greeted with dismay from some Labour MPs and unions after the party pledged to end “discriminatory” lower minimum wage rates for younger workers so that all adults would be entitled to the same legal pay floor.

In a warning to Labour on Friday, Andrea Egan, the incoming general secretary of Unison, wrote in the Guardian that she would “call time on our union’s inexcusable habit of propping up politicians who act against our interests, undermine our fundamental values, and make our lives worse”.

As Keir Starmer struggles against a backdrop of difficult poll ratings, Milburn, a veteran of Tony Blair’s government, suggested this one could still turn around its fortunes if it was able to generate hope for the future. He said transforming young people’s prospects could do that.

But he said that without substantive action, the UK was at risk of abandoning a whole generation to a life on benefits and could push them away from mainstream parties towards rightwing populism.

After launching his review of why a quarter of 16- to 24-year-olds are not in education, employment or training earlier this week, Milburn said they faced a “perfect storm” in the youth labour market after the Covid crisis, with systemic failures and policy neglect in education and welfare over decades.

“You write off a generation, you write off the country’s future,” he said. “You’ve got this sort of downward escalator: we’re plunging young people into a lifetime on benefits, rather than creating an upward escalator, with opportunities for people to learn and to earn.”

The former cabinet minister is not shying away from recommending radical reform of the system in his final report, due in the summer. He said he was prepared to look at pressure on employers and the steep rise in mental health claims.

Before the budget, Treasury insiders were among those who were concerned about the increase in youth rates of the minimum wage, amid fears they could be priced out of entry-level jobs.

“We’ve got to look very carefully at exactly that,” Milburn said. “We’ve got to make sure that in a fragile youth labour market, and it’s been fragile for very many years, that public policy is providing the right incentives for employers to employ more young people, rather than less.”

Asked whether he thought businesses had been squeezed too much by the government, which put up national insurance at the last budget, he added: “I hear that being said. I’m going to examine the evidence, and we will reach a conclusion.”

Milburn also wants to address sensitive issues around the mental health of young people, citing it as a reason for a sharp rise in sickness benefits in recent years.

“We’ve got to be careful that just because you’ve got anxiety or depression, that automatically puts you on to the downward escalator into the world of benefits,” he said.

“We’re at real risk in the debate that’s taking place sometimes, of a new currency developing which says that work is bad for people’s mental health, whereas the opposite of that is true, which is good work in particular, is extremely good for people’s mental health.

“When I talk about these uncomfortable truths that the review is going to have to confront, you know, this is one of them.”

The health secretary, Wes Streeting, has ordered a clinical review of the diagnosis of mental health conditions in England, which will inform Milburn’s review.

However, the Labour veteran said 16- to 24-year-olds were a “generation under duress”. They faced a different world from their predecessors, who had a “social transaction” with the state that no longer existed.

“It’s very easy to play the blame game ... but we’ve got a job to act as custodians, to make sure that young people have got the right opportunities in front of them,” he added, saying that the government and business needed to step up.

They had a responsibility, in particular, to prepare younger generations for “tomorrow’s potential tsunami” – the advance of technology – which could send further shockwaves through the youth labour market.

“You can’t simply say, King Canute-like, we’re going to resist the forward march of technology. That’s not possible. What we have got to do is equip people to be able to adapt, be agile enough, to have enough resilience, to be able to succeed in that labour market,” he said.

With Labour losing support among younger voters, many of them disillusioned by a political system they feel is entrenching generational inequality, Milburn said young people were deserting the mainstream parties.

“If young people start feeling society isn’t interested in me, to this question of how they’re thinking of potentially voting in future, then there’s an obvious quid pro quo,” he said, suggesting that they could turn to Reform UK instead.

“That should be something that people would want to avoid, particularly people who are concerned about progressive politics. It’s pretty obvious that that social contract is being broken”.

Milburn, who is close to Streeting – regarded as a potential successor to Starmer if he stands down – urged the government to be more optimistic about what it could deliver. “The centre-left of politics only wins when it creates a sense of possibility about the future,” he said.

“So my very strong advice would be generate hope for the future. This [review] is about saying the future can be better than the present and better than the past. It is about making sure that we’re investing in the future generation. The biggest deficit in the country is the shortage of hope.”

Pat McFadden, the work and pensions secretary, is planning to propose further welfare reform next year, after the government abandoned a significant part of its bill in June under pressure from Labour MPs.

Milburn, whose review is reporting to McFadden, said the government had “self-evidently” got its attempts to win MPs round on welfare badly wrong. “Framing welfare reform as a cost-out measure wasn’t a sensible approach to take, and it produced the inevitable result,” he said.

“If you want to reduce welfare bills, the only way of doing that is to provide more opportunities for people to learn and to earn first.”

1 month ago

72

1 month ago

72