In June 2024, an Israeli missile struck 13-year-old Mazyouna Damoo’s apartment in Nuseirat refugee camp in central Gaza, hurling her and her mother into the street.

Her younger sister, Tala, was pulled from beneath the rubble alive, but her other siblings – Hala, 13, and Mohannad, 10 – were killed instantly. Mazyouna survived, but half of her face was ripped off, leaving her jawbone exposed.

More than a year on, Mazyouna’s journey and ongoing recovery in a hospital in the US has become a rare story of hope from the two-year Gaza war that has now entered a ceasefire. But it was a recovery that almost never happened.

With Gaza’s hospitals overwhelmed and unable to provide advanced reconstructive surgery, her family’s pleas last year for evacuation became desperate. For months, her parents appealed to the Israeli body overseeing humanitarian permits to allow Mazyouna to leave Gaza for treatment. Each request was either ignored or rejected.

During this time, her wounds worsened, becoming infected, and fragments of shrapnel embedded in her face caused excruciating pain. After the Guardian reported on her ordeal, Israel finally permitted her to leave to get surgical care.

Last November, Mazyouna, her mother and her surviving sister travelled to the US for her medical treatment, settling in El Paso, Texas. It has been almost a year since they moved into a home on a quiet, tree-lined street with views of the Franklin mountains, and the family have tried to adjust to life in the US as best they can.

Mazyouna and Tala have started attending a local school, where they have made new friends and worked hard to catch up on the year of education they missed in Gaza after the war began. When Mazyouna first arrived, she didn’t know any English, but now speaks it with growing confidence, as well as some Spanish. She already has new dreams for her future.

“When I grow up, I want to be a doctor and help kids like me. I feel really lucky to have survived and gotten the care I needed. One day, I hope I can help others the way the doctors here have helped me,” she says.

Over the course of a year, Mazyouna has undergone multiple surgical procedures. Under the care of the El Paso children’s hospital, she has had her cheek and lips reconstructed, as well as the missing jaw bone that was destroyed in the blast.

“Our goal is to address the visible facial deformities and restore the basic structure and appearance of Mazyouna’s face,” says lead surgeon Dr Arshad Kaleem. “This is a multi-stage reconstruction process, which is still ongoing and we’ll need to plan and adapt as she grows to ensure the best outcome.”

Mazyouna will require dental implants and teeth once her current growth spurt stops. But in the meantime, the doctors have put temporary measures in place, including a partial, removable prosthesis to aid with chewing and tooth positioning. As a result of her surgeries, she is able to eat, drink and speak more easily.

after newsletter promotion

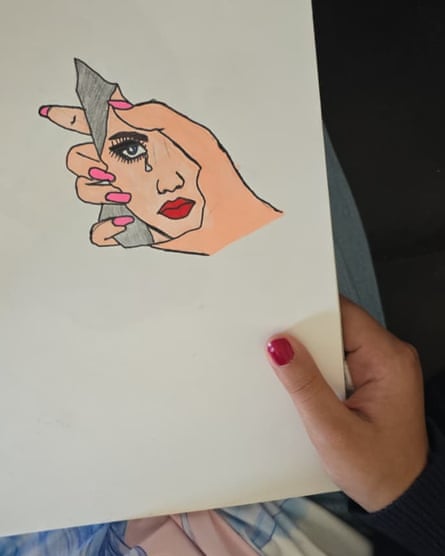

Since removing the bandages from her face, the young teen has also gained a new sense of confidence and self-esteem, says her mother, Areej Damoo. On an autumn afternoon, the girls dance around in thobes, long black robes, adorned with red, hand-stitched tatreez, a centuries-old embroidery technique passed down through generations and often used to tell the story of Palestine.

“Mazyouna and Tala love dressing up, especially in traditional Palestinian clothes, which they rarely get to wear any more. Mazyouna’s grandmother would sit and tell the children stories of our homeland, but she was killed during the airstrike,” says Areej. “It is important for me to honour these traditions and preserve our culture so the girls don’t forget who they are. Gaza is so much more than war and I want them to grow up proud of where they’re from.”

The girls’ father, Ahmed Damoo, was not allowed to join them in the US and remains in Gaza. In August, the US imposed sweeping visa restrictions on Palestinians, citing security concerns and a review of vetting procedures.

Ahmed hopes to be resettled in another country – somewhere his wife and children could one day join him so they can start rebuilding their lives. “The thought of being reunited with my girls is what has kept me alive for this long,” he says.

Last week, Kaleem returned from a medical aid trip in Gaza, during which he had the chance to meet Ahmed in person. “I had heard so much about Ahmed from his daughter and it was a real honour for me to finally meet him,” he says.

During their brief encounter, Ahmed thanked Kaleem for treating Mazyouna and asked him to watch over his wife and children. “He is such a gentle, loving man but I could see the weight of sorrow in his eyes as he spoke about the family he has cruelly been separated from for so long.

“No matter how much we do for her here, the best medicine for this little girl is to be reunited with her father.”

Back in Texas, Areej says the mental toll from the horrors of war is hard for the girls to escape. Sometimes they have trouble sleeping, she says, waking up in the middle of the night with tears streaming down their faces. Ordinary sounds, she says, like the rumble of thunder or the distant pop of fireworks, can suddenly transport them back, triggering anxiety and paralysing fear.

Mazyouna says her scars also continue to draw unsolicited attention and questions from curious classmates. “It’s still hard for me to talk about. I try not to think about all the terrible things that happened in Gaza, but it is difficult when that’s all people want to talk about.”

3 months ago

73

3 months ago

73