Bird migrations rank as one of nature’s greatest spectacles. Thanks to GPS tracking, scientists are uncovering extraordinary insights into ancient and mysterious journeys – and new threats that are reshaping them.

Bird migrations rank as one of nature’s greatest spectacles. Thanks to GPS tracking, scientists are uncovering extraordinary insights into ancient and mysterious journeys – and new threats that are reshaping them.

As storm-chasing seabirds, Desertas petrels seek out hurricanes that draw deep-sea creatures to the surface. Only about 200 pairs remain, although the population is stable.

Each bird is no bigger than a pigeon and they all breed on a single deserted island off the west coast of north Africa, fanning out across the Atlantic Ocean to forage.

Among the 35 birds that have been tracked by GPS is “Marlo”, which was born on Bugio Island and tagged after returning there in 2019. Males and females are virtually indistinguishable, so researchers do not know the sex of Marlo but we will refer to him as “he”.

Marlo is part of a pair bonded for life, and he and his partner reunite with a flurry of excitement after months apart, preening and calling to each other. The parents raise one chick as a tag team, doing long shifts at sea for up to three weeks at a time, covering distances of up to 7,400 miles (12,000km). They gorge on seafood and regurgitate it as oil for their chick.

Francesco Ventura, from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, says: “The routes they take are some of the longest collected for any animal during breeding season. It’s like travelling to the other side of the Atlantic for a food shop.”

Once his chick successfully fledged, Marlo departed Bugio on 2 November 2019, and did not touch land until June of the following year. Like all Desertas petrels, Marlo spends the majority of his life soaring above international waters.

Typically, the young spend the first few years of their life out at sea without touching land. No one knows where they go. If they survive these early years, they typically live for decades.

In September 2019, Marlo flew out over the Atlantic Ocean and came across the cyclone that was developing into Tropical Storm Gabrielle. Researchers tracing their migrations have discovered that petrels actively steer into storms, perhaps reading changes in air pressure, cloud patterns and the swell of waves to find them.

“To me, this looks like intentionality,” says Ventura, who was part of the first team of researchers to track this behaviour in Desertas petrels.

For 19 days, Marlo chased the tropical storm’s wake, covering nearly 7,000 miles and reaching speeds of 41mph (66km/h). Hurricanes churn up cold, nutrient-rich water, which draws deep-sea squid and crustaceans to the surface where birds can catch them.

Climate change threatens the prey these seabirds depend on because the marine creatures are so sensitive to changing temperatures, sometimes shifting northwards and deeper as the ocean warms.

Marlo covers as much ground as possible to maximise his chance of catching something, hunting at night and using smell to locate prey in the darkness. “They don’t flap,” says Ventura. “They surf the wind.”

Weighing no more than a large strawberry, the nightingale manages to cross the Sahara twice a year as part of a 6,000-mile round-trip between its spring breeding grounds in England and overwintering ground in west Africa.

But their journey is becoming increasingly fraught and their destination less welcoming.

“Berkeley” is a one-year-old nightingale tagged near Alton Water, a nature reserve a few miles south of Ipswich in the UK. He was caught on the 31 May 2023 in a dense patch of bramble and blackthorn, and fitted with a GPS tag the weight of a paperclip.

During the summer Berkeley would have tirelessly gathered beetles, ants, flies and caterpillars to feed his young. Once his family had flown the nest, he was ready to migrate south.

Berkeley waited for the perfect night in late August before leaving: mild, clear and still. He crossed the Channel and flew down the west coast of France to Spain where he spent three weeks recuperating and putting on fat before tackling the Atlantic Ocean and Sahara.

Some nightingales may make this crossing in a couple of days straight; others will stop during the day, resting at a desert oasis if they pass one.

Climate crisis-driven droughts and wildfires in southern Europe, however, mean more birds are dying over the Sahara as they are forced to continue their migration without getting into prime flying condition.

Bad weather can also throw them off course, and they are hunted by the giant noctule bat over the mountains of the Iberian peninsula. Berkeley flew high over the desert at about 5,000 metres to stay cool, and managed to dodge all these threats.

On 26 September, five weeks after leaving Alton Water, he arrived in Senegal. “Before leaving they should have a nice chunky body and rounded chest. By the end, it’s an emaciated thing,” says Chris Hewson, who tracks these birds for the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO).

After a gruelling journey, the vast majority of nightingales winter in Senegal, the Gambia and Guinea-Bissau, but this area has become increasingly threatened since the 1960s due to severe droughts, less rainfall and a bigger human population, collecting firewood and grazing livestock. This has led to irreversible changes and reduced the quality of their habitat.

The birds’ habitat in Britain has also been very degraded, with increased numbers of deer, reduced scrub and woodlands. The nightingale population documented in Britain has fallen by 91% over the past 50 years, and the loss of suitable habitat at both ends of their migration is driving that decline.

Understanding exactly where the birds are by using more precise GPS tags will help ecologists do more focused conservation work in the areas of highest importance.

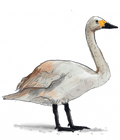

Bewick’s swans are one of the heaviest long-distance migratory birds. Their migration of nearly 2,200 miles takes so much energy they have to refuel every few hundred miles.

They were once dependent on aquatic plants but since the 1960s – when agriculture intensified across northwestern Europe – they have switched to feeding on grass and crops, and can eat throughout north-west Europe.

“Mary” was caught and tagged on 20 December 2016 in North Brabant province in the Netherlands. She was at least four years old and caring for a cygnet.

By the following spring, she had embarked on a long journey north, arriving in the breeding grounds in the remote and wind-swept Malozemelskaya tundra, an area of the Arctic in northern Russia dominated by bogs and wetlands. In September, she set out from the tundra on her autumn migration south, flying to western Latvia, then to Lower Saxony in northern Germany for the winter.

As Europe warms, Bewick’s swans are making much shorter journeys to ice-free wetlands and agricultural areas in the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark and Poland – known as short-stopping. Britain has lost an estimated 43% of its Bewick’s swans in five years.

About 60 swans are carrying GPS collars on their necks. Tracking data shows that swans adjust their autumn journeys on a daily basis. On colder days, the birds travel bigger distances but if it is warm, they sometimes do not move at all.

“If they spend their winter closer to the breeding range, the distance that they have to go for the next spring is also shorter, which also enables them to migrate faster,” says Linssen.

The Bewick’s swan population is rapidly declining, but this might have more to do with illegal hunting than climate change, says Linssen. Up to a third of Bewick’s swans in the UK have lead pellets from shotgun shells or fishing weights embedded in their bodies.

Other potential pressures include competition with other species such as whooper and mute swans on spring migration stopovers, and predation of eggs and hatchlings in the Arctic as predators such as red foxes shift farther north.

Illustrations by Tina Zellmer, graphics by Heidi Wilson and Harvey Symons

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow the biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield in the Guardian app for more nature coverage

Methodology

Global temperature data came from CHELSA’s daily mean air temperatures measured from hourly ERA5 data, spanning from 1981 to 2010. Global vegetation data came from Nasa’s Terra/Modis monthly vegetation index, NDVI 2024. The world map borders, relief, and land-use colours are from Natural Earth.

For the flight paths in the Americas, we used the migrations of 30 of the 118 species tracked in this study. European flight-path tracks were from this 2016 GPS tracking dataset in northern and eastern Europe.

Desertas petrel migratory flight paths were part of this study, while the detailed hurricane-hunting flight path was plotted from data provided by Francesco Ventura and his colleagues. Wind and speed direction data was taken from the Copernicus ERA5 dataset, and the hurricane track comes from NOAA. The audio was recorded by Ben Metzger.

The nightingale’s journey was built from the GPS tracking of two birds in 2023. The tracks and suitability map data was supplied by the BTO’s Chris Hewson and Máire Kirkland from their study on migratory connectivity. The audio was recorded by Grzegorz Michalski.

The Bewick’s swans’ migratory paths were provided by Hans Linssen and used in this study on how migratory swans adjust to a warming climate. The audio was recorded by David Darrell-Lambert.

With thanks to Joanne Morten from BirdLife International for her guidance on seabird migration data and paths, and to Jon Carter from the BTO for sourcing information at the start of the project.

Bird facts about the nightingale and Bewick’s swans came from the RSPB; information about the Desertas petrel was from the Madeira birds website.

Citations:

Climatologies at high resolution for the Earth land surface areas

DN Karger; O Conrad; J Böhner; T Kawohl; H Kreft; RW Soria-Auza; NE Zimmermann; P Linder; M Kessler; 2017

Convergence of broad-scale migration strategies in terrestrial birds

FA La Sorte; D Fink; WM Hochachka; and S Kelling; 2016

GPS tracking of Storks, Cranes and birds of prey, breeding in Northern and Eastern Europe

K Adojaan; U Sellis; Ü Väli; I Ojaste; K Denac; A Lõhmus; J Ķuze; BirdMap Data – GPS tracking of Storks, Cranes and birds of prey, breeding in Northern and Eastern Europe. Data accessed via GBIF.org

Oceanic seabirds chase tropical cyclones

Francesco Ventura; Neele Sander; Paulo Catry; Ewan Wakefield; Federico De Pascalis; Philip L Richardson; José Pedro Granadeiro; Mónica C Silva; Caroline C Ummenhofer; 2024

Extreme migratory connectivity and apparent mirroring of non-breeding grounds conditions in a severely declining breeding population of an afro-palearctic migratory bird

Máire Kirkland; Nathaniel ND Annorbah; Lee Barber; John Black; Jeremy Blackburn; Michael Colley; Gary Clewley; Colin Cross; Mike Drew; Oliver JL Fox; Vicky Gilson; Steffen Hahn; Chas Holt; Mark F Hulme; John Jarjou; Dembo Jatta; Emmanuel Jatta; Kevin Leighton; Ernestina Mensah-Pebi; Chris Orsman; Naffie Sarr; Roger Walsh; Leo Zwarts; Robert J Fuller; Chris M Hewson; 2025

Migratory swans individually adjust their autumn migration and winter range to a warming climate

Hans Linssen; E Emiel van Loon; Judy Z Shamoun-Baranes; Rascha JM Nuijten; Bart A Nolet; 2023

3 months ago

105

3 months ago

105