Helen Chadwick, who died unexpectedly in 1996 at the age of 42, has long been an artist more name-checked than exhibited. Her devotees include the lauded feminist mythographer Marina Warner, for whom she’s “one of contemporary art’s most provocative and profound figures”. Yet she is habitually relegated to a footnote within British art: one of the first women to be nominated for the Turner prize in 1987 and an outstanding teacher of YBAs such as Sarah Lucas, Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst.

She remains best known for Piss Flowers, her white bronze sculptures whose stalagmite protuberances are phallic inversions of vaginal recesses, cast from the holes she and her husband made by peeing in thick snow. (The artist’s hotter urine went deeper, creating larger cavities. She described the work as “a penis-envy farce”.) It’s easy to see how her transgressive interests might have quickened British art’s pulse. Yet her meditations on the sacred and profane, sex and death, were expansive, propelling diverse experiments across installation, photography and performance.

Now, her prolific if all too short career is getting its first major showing in more than two decades. At a time when gender binaries are being dismantled, Laura Smith, curator of a retrospective at the Hepworth Wakefield, Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures, and editor of the accompanying book, hopes to make Chadwick’s relevance to a fresh generation clear.

“She was trying to disrupt societal conventions, including gender normativity,” Smith says. “She was really pioneering and she wasn’t afraid of art being sexy or funny, either.”

The exhibition opens with the decidedly fluid Cacao, one of Chadwick’s most affecting evocations of how opposites such as desire and abjection entwine. It’s a huge chocolate fountain set to be filled with 800kg of Tony’s Chocolonely, which will gush from a central liquid erection. Needless to say, this brown pool evokes more than confectionery. “It’s joyous and kind of gross,” says Smith. “It bubbles like a swamp. Basically, it farts.”

Chadwick was also an inveterate craftsperson. The images of her MA graduation show of 1977, In the Kitchen, where she’s encased in sculptural costumes of white goods, are often used to represent feminist art of that decade. What the pictures can’t tell you is what went into those creations, including performances with wearable beds and latex nudity suits cast from their wearers’ bodies. According to Errin Hussey, who’s overseeing an exhibition in Leeds of her archive, “the costumes really show the dedication she had. The intricacy of detail and planning that went into the textile and metalwork on just one shoe is amazing.”

For her first major work, Ego Geometria Sum, she devised a novel way to embed shots of herself on to the plywood surfaces of sculptures by painting them with photographic emulsion. The Oval Court, part of the exhibition that led to her Turner nomination, took the experimentation further. She created its dreamy blue-and-white collage with a photocopier, making direct images of her own body alongside an apparent cornucopia of flowers, fruit and dead animals including lambs and a swan.

Complementing this lusciously libidinal work is Carcass, a glass tower that, when originally shown at the ICA in 1986, was filled with dead animals’ bodies, plus weeks of kitchen waste. When the gases generated by its live decomposition caused its glass to crack, and the gallery attempted to remove it, the lid blew off, spraying rot across the art space. (At the Hepworth, its vegetarian recreation features a gas valve so it can be “burped like a baby” each night.)

In what would be her final decade, frustrated by the heat she was getting from fellow feminists about her use of nudity, she abandoned depicting her outer body and looked within instead. Moving on from questions around objectified gender towards a polymorphous, fluid sexuality, in these works things are forever collapsing into their opposite, like Piss Flowers’ erect recesses. As Smith reflects: “In her thinking nothing was black and white.”

The ins and outs of it: five pieces by Helen Chadwick

Viral Landscapes, 1988-89

In this work created after Chadwick stopped depicting her outer body, photography of Pembrokeshire’s coast is overlain with images of cells taken from her urine, blood, cervix, mouth and ear.

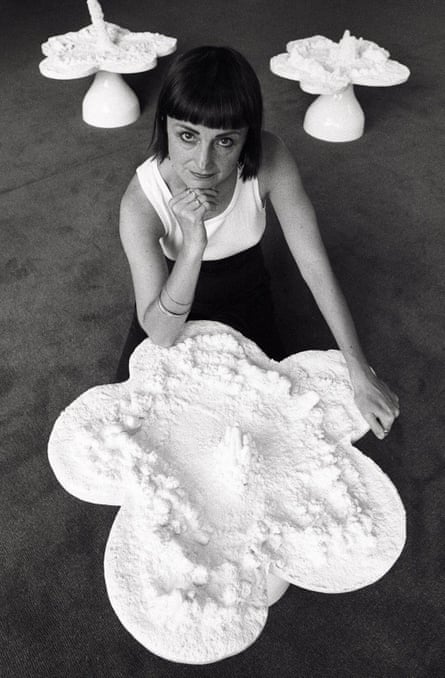

In the Kitchen, 1977 (main image)

Chadwick’s earliest works hinged on feminist concerns about constructed identity. For her MA degree show she and her performers donned sculptural costumes of white goods and made a tongue-in-cheek speech about “kitchen lib” to a soundtrack of clips from daytime radio aimed at housewives.

after newsletter promotion

Piss Flowers, 1991-92

Chadwick’s Piss Flowers first made a scatalogical twosome with her chocolate fountain sculpture Cacao at her exhibition Effluvia at the Serpentine Gallery in London in 1994. The press had a field day but the show attracted record numbers to the venue: 54,000 visitors in six weeks.

The Oval Court, 1984-86

In this sculptural installation featuring collage on a large, low platform, the artist created a vision of baroque excess using blue-and-white images of her own body, flora and fauna made with a photocopying machine. Unlike the finger-wagging Vanitas paintings Chadwick drew on, its vision of life’s transient pleasures mixed with death has a luxuriant, unbridled energy.

Loop My Loop, 1991

Chadwick had a genius for evoking the slippage between desire and disgust. Here, she entwines the age-old lover’s keepsake, a lock of golden hair, with pig intestines. Airy romance meets bodily urges; the human entwines with the animal. Where does one begin and the other end?

Helen Chadwick: Life Pleasures is at Hepworth Wakefield, 17 May to 27 October; the book of the same name is published by Thames & Hudson (£30); Helen Chadwick: Artist, Researcher, Archivist is at Leeds Art Gallery to 4 November.

6 hours ago

9

6 hours ago

9