Although he was the youngest of the Liverpool trio that launched the popular poetry revolution of the 1960s, Brian Patten was arguably the catalyst whose enthusiasm and single-minded dedication did most to bring the whole phenomenon into being.

Patten, who has died aged 79, was first linked with Roger McGough and Adrian Henri when, early in 1962, as a 16-year-old pop journalist, he wrote about them in his column in the Bootle Times. He had met McGough, a Hull University graduate, and Henri, a painter and jazz musician, on the Liverpool club scene, and was already taking their poems for Underdog, the little Xeroxed magazine he edited, to sell in clubs and pubs and at a few sympathetic bookshops.

At a time when pop, comedy and poetry went naturally together, they rapidly became a well-known group – later categorised as the “Liverpool poets” – and two, or all three, of them would join to read their poems to audiences at every opportunity, in Liverpool or anywhere else they were invited. Tenderness and melancholy ran alongside the sad jokes and fantasies in the poems of Patten, the secondary modern boy from, in McGough’s phrase, an “awful deprived background”. This work related to the mood of the young in Liverpool in a way that the more sophisticated range and humour of his colleagues did not attempt. But the warm appeal of all three as skilled performers ensured their success.

And Patten was no slouch with Underdog: as well as publishing McGough, Henri and numerous other British poets, he circulated it in the international world of foreign poets he admired. Soon he was featuring work by the Americans Allen Ginsberg and Robert Creeley, and by Andrej Voznesensky, celebrated and controversial in the Soviet Union.

Born in Liverpool, Brian was the only child in a desperately poor family. He never knew his father, Frederick, and had no interest in finding out about him. His childhood was spent in a tiny house in Wavertree Vale with a mother, Irene (nee Bevan), in whom he took years to discern any genuine affection, a formidable aunt, and grandparents who did not speak to each other. If Lawrence Road junior school (where he was reported to have been the last to read and write in his class) or Sefton Park county secondary school for boys (which he left at 15) were happier places than home, he acknowledged only one form teacher at Sefton Park, Harry Sutcliffe, for recognising some school work impressively done, and the headteacher, AT Woolley, for giving it special praise.

But no one detected any particular gift in the young Brian, or inspired him to be creative. A loner then, as he continued to be all his life – “There’s something of the cat in him,” said McGough – he seems to have discovered both his wide reading and his writing talent for himself.

After their encouraging start, the three Liverpool poets lived and worked in separate places from the mid-1960s, Patten and then McGough moving to London and Henri remaining in Liverpool. But the firm friendship continued, as did their collaboration in popular, well-attended tours.

By 1967, observant cultural critics and alert publishers had spotted a definable “Liverpool scene” (exuberantly put on record in the book of that name by the poet and critic Edward Lucie-Smith), and Penguin published The Mersey Sound, which became its bestseller in their already flourishing Modern Poets series. Patten’s teenage poems there, drawing largely on his simultaneous debut volume, Little Johnny’s Confession, anticipated what he was to become: a rebellious romantic for whom poetry was never to be conventional or easy.

In Prose Poem towards a Definition of Itself, he concluded: “It is the monster hiding in a child’s dark room, it is the scar on a beautiful man’s face. It is the last blade of grass picked from the city park.”

Parallel with this went McGough’s success with his own poetry and his Top of the Pops fame in the late 60s with the Scaffold, the music, poetry and revue group. When the Scaffold fused with the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band to form Grimms in 1971, working with figures such as Viv Stanshall and Neil Innes, Patten was invited – Henri soon came in as well – to join this larger group. Patten’s association lasted almost throughout the three years of its anarchic touring existence, as reader, occasional presenter and contributor to its albums, with a voice described by the poet Adrian Mitchell as having “all the colours of a melancholic alto sax”. Henri died in 2000.

A succession of individual volumes from Patten that commanded impressive sales, including Vanishing Trick (1976), Grave Gossip (1979) and Storm Damage (1988), culminated in 1996 with Armada, a collection in which, after her death, he came to terms movingly with his relationship with his mother and his painful childhood, in a deprived neighbourhood he nevertheless felt betrayed to see “pulled down and replaced / And my background wiped from the face of the earth”.

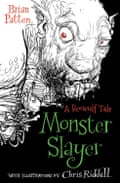

Armada proved to be his most notable book for adult readers and it arrived in a period of his life when he had already turned his talent towards producing poetry and fiction for children. The titles (and the illustrations accompanying them) of Gargling with Jelly (1985), Thawing Frozen Frogs (1990) and, later, Juggling with Gerbils (2000) suggested that they might be no more than run-of-the-mill light verse ventures. Not so. Patten’s resource with rhyme and plotting and his clever updating of traditional wisdoms – see Winifred Weasel or Mr Ifonly (“I could really have lived if only I had tried ...”) – revealed him to be a children’s poet of distinction.

As early as 1975 there had been a strange and remarkable prose fantasy, Mr Moon’s Last Case, in which the eponymous police inspector tries to track down a dwarf, who could be a leprechaun. No one except Patten had, or has, written anything quite like this eerie allegory of powerless authority pursuing an imaginary creature in which many people (but all children) actually believe.

The sheer number of his love poems, and their popularity at readings, encouraged the publication of ample collected editions. Part of their appeal lies in their apparent intimacy and authenticity in treating the subject of love in a modern world; but they in fact belong to an older tradition, which saw love as energising and revitalising and at the same time the creator of confusion and chaos: “Nothing can be pinned down or fully explained. / You are afraid. / If you found the perfect love / It would scald your hands ... ” he wrote in And Nothing Is Ever As You Want It to Be.

Though Patten was not the equal of Robert Graves (whom he had visited at his home in Deià, Majorca, when young) as a love poet, his long exploration of love in all its moods and changes at least makes the comparison possible.

There is much sadness and loss in the love poetry, and in later years his poetry included moving elegies to departed friends. But in the end, what Patten says about the tramp who befriends the little figure in Mr Moon’s Last Case could be said to apply not only to these poems but to all his endeavours as a writer: “He moved, spoke, gestured and breathed as if he knew for certain that behind the drab winter clouds a different kind of sky was waiting, and that beneath the exhausted and frost-bitten ground lurked every imaginable flower.”

In 1970 he developed a passionate connection with Mary Moore, daughter of the sculptor Henry Moore, who was the dedicatee of his 1971 book, The Irrelevant Song; it gave him crucial encouragement in his writing for children. This relationship lasted until 1975 and was until then his longest and most important one. In 1994 he formed a lasting partnership with Linda Cookson, a travel writer, with whom he lived in Dittisham, Devon, and whom he married in 2015. She survives him.

Brian Patten, poet and author, born 7 February 1946; died 29 September 2025

2 months ago

69

2 months ago

69