Confident in his popularity, the Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet called a plebiscite in 1988 asking the population whether they approved extending his 15-year-long bloody rule for a further eight years.

A young José Antonio Kast, then a 22-year-old law student, joined the yes campaign, saying in a TV advert that he was convinced the regime was acting “for the direct benefit of all of us young people”.

Pinochet ultimately lost and left power in 1990, but Kast never stopped openly supporting the dictator, both as a congressman and in the three presidential bids he made before being elected last Sunday.

The president-elect – whose older brother, Miguel, was a prominent figure in the regime, serving as a minister and president of the central bank – once said that if Pinochet were alive “he would have voted for me”.

A majority of today’s Chileans did, and the victory of the first openly Pinochet-admiring candidate has left many around the world asking why the country chose as its next leader a defender of a brutal regime under which an estimated 40,000 people were tortured and more than 3,000 killed.

“The truth is that support for Pinochet among part of Chile’s population never disappeared,” said Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, a populism researcher and professor at the Institute of Political Science at the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

He noted that although the dictator lost the 1988 plebiscite, he still secured 44% of the vote. Since then, that support has shifted to rightwing parties, notably the Unión Demócrata Independiente (UDI), which, over time, became more “moderate” under the leadership of the two-time president Sebastián Piñera.

“But there were always some leaders who were bothered by that moderation, and one of them was Kast, who decided to break with the UDI, arguing that the right had lost its way and needed to return to much more authoritarian roots,” said Kaltwasser.

Although stressing that other factors, such as populist public-security proposals and the promise to expel undocumented migrants, played a role in his election victory, Kast managed to “reactivate that dormant Pinochetism”, said Kaltwasser.

A recent opinion poll showed that about a third of Chileans agree that Pinochet was one of the “best political leaders in the country’s history” or that, if politicians followed his ideas, the country would “regain its place in the world”.

“The fact that a Pinochet admirer won shows that the current generation has forgotten or does not know enough about the horrific crimes committed during the dictatorship,” said Katia Chornik, a research associate at Cambridge University’s Centre of Latin American Studies.

Her parents were political prisoners and raised her in exile, between Venezuela and France. Years later, as a teenager returning to Chile in the 1990s, Chornik learned that they had been held in a torture centre in the capital, Santiago, cruelly nicknamed La Discothèque by secret police agents because of the loud music they used to torture detainees.

“When I first learned this, I was already studying music, and the idea that it could be used for very negative purposes really affected me,” said Chornik.

She later conducted a decade-long research project, interviewing dozens of survivors, former prison guards, and convicted perpetrators from the higher echelons of Pinochet’s regime, and launched the digital platform Cantos Cautivos (Captive Songs), which features 168 of those testimonies.

Her research was published on Friday as the book Music and Political Imprisonment in Pinochet’s Chile, in which Chornik provides examples of how music was also used as an act of resilience among political prisoners.

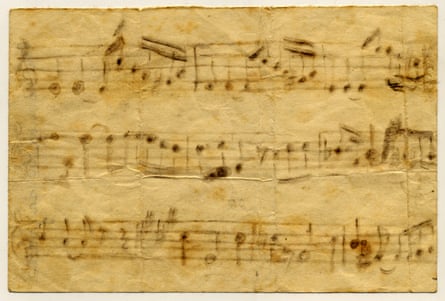

She recounts the case of Jorge Peña Hen, a respected Chilean conductor and pedagogue, regarded as the founder of the first children’s orchestra in Latin America, who was detained shortly after the 1973 coup.

While held in the Cárcel de La Serena, Peña Hen wrote an unfinished 10-bar melody on a scrap of paper, using burnt matches. He was murdered soon afterwards. Ten years later, his children found the manuscript: “Without opening it, I brought the paper to my nose. Closing my eyes, I breathed in deeply, and I felt my father’s scent permeate my soul,” his daughter, María Fedora Peña, told Chornik.

Chornik is now working with Unesco on a project to bring her research into classrooms across Latin America and the Caribbean.

“With Kast’s election, it’s clear that people have forgotten or don’t have enough information about the horrors of the dictatorship, so education is absolutely key,” she said.

1 month ago

53

1 month ago

53