This haunted fairground of an exhibition has its heart in the right place. But that is not enough. Called The Delusion, it is a woolly mess of platitudes and phoney dialogue. Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley is worried about the polarisation of online discourse and 21st-century politics. Aren’t we all? But the remedies offered are confused, and the attempt to create a free, open discussion is stymied by its coercive tactics.

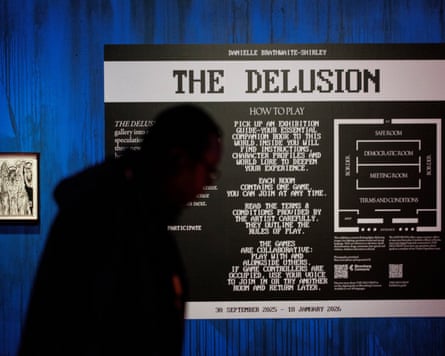

You can’t say you weren’t warned. A huge text at the beginning explains the artist’s “Terms and Conditions”, including the instructions to “Join others, experience this together”, and to “talk, share, listen and question out loud”. Do I have to? Yes. As I look at an arcade-like machine in a cabinet behind a glass door, someone asks me firmly, “Did you open the door? Well, you should open it.” So I open it, answer some questions in the negative and am told off again, this time by the machine, for holding back.

The Delusion uses technology as a cover for artistic paucity, and expects interaction instead of giving anything much itself. It confirms my suspicion that participatory art is a bit lazy, expecting the audience to do the heavy lifting. After reading the rules, you walk around a low-lit space with arcade-style machines among satin drapes leading to ouija-like tables. There are so-so cartoons on the walls in which multi-eyed monsters make comments about hate and oppression. They are the best bit – at least the artist sat down and doodled them.

Words such as “hate”, “polarisation” and “dehumanisation” are thrown around but their meaning is never spelt out. That is your job. One of Brathwaite-Shirley’s team, politely, tried to get me to discuss the question, “Why do we dehumanise people?” I said I can’t debate an abstract proposition, it needs to be more specific. For instance, I reckon Nigel Farage dehumanises migrants. Why? Perhaps because he hates them, but that’s merely my speculation: I don’t know his motives. He may be a completely cynical politician who doesn’t mean a word he says. The answer I got was something about community solidarity. It seemed inadequate and pre-scripted. And the conversation stopped there, as if we had been talking about different things.

As a physical exhibition, this isn’t all bad, but the more you do as you are told and interact, the less fun it is. At the press view, there wasn’t much sign of anyone else getting intensely involved in the games and stilted conversational starters – and if you can’t get journalists to mouth off, who will? I don’t think this is what anyone goes to galleries for, to debate with strangers as opposed to, say, being alone with their thoughts looking at art.

Another game asks if you need to be dehumanised to commit war crimes. But what does “dehumanised” actually mean? The guards at Auschwitz were still human beings. It’s a way of reassuring ourselves to say they were “dehumanised”. Such sterile use of language strips this art of meaning. Brathwaite-Shirley poses a series of supposed moral and political questions but they are all expressed in the same strings of predefined and loaded terms. “Hate” is a word that needs, to quote Lenin on power, the terms “Who? Whom?” to mean anything.

This artist, I fear, spends too much time online. The insults, aggressions and extremist views that fly on social media create false, ugly, limited world views. This exhibition wants to talk past those views but mistakenly conflates online verbiage with real life. “Hate” is used here in the way it’s used in online forums. You hate. I am hated. While The Delusion wants to combat the “polarisation” of today’s largely digital controversies, it chokes itself on the very rhetoric those arguments spew out.

Perhaps in this way it has something to teach. George Orwell argued in his 1946 essay Politics and the English Language that ideology was destroying our language with abstractions and evasions. He imagined this process taken to a totalitarian extreme as 1984’s “newspeak”. If you can’t talk about ideas clearly and critically, how can you have the open, democratic debates Brathwaite-Shirley aspires to unleash?

after newsletter promotion

It all seems a sad image of liberals tying themselves in paralysing knots of dead language that get in the way of persuading anyone. Meanwhile, avuncular Nigel uses plain words every Englishwoman and Englishman understands and stokes fires with the power to burn everything.

-

Danielle Braithewaite-Shirley: The Delusion is at Serpentine North Gallery, London, until 18 January

2 months ago

63

2 months ago

63