All that drinking. All that smoking. All that free love and those bohemian goings-on, all that Nietzschean nonsense, the symbolism and the expressionism, all that madness and early death. These are the reasons we seek out the company of laugh-a-minute, devil-may-care bon vivant and man-about-town Edvard Munch, a selection of whose portraits are now at London’s National Portrait Gallery. Sadly, little of the drama we expect of his art is in evidence here. Most of it is in the catalogue and on the wall labels, in the things the paintings here don’t tell us.

Where are the sickroom scenes and the fights, the houses on fire and the shootings, the breakdowns and suicides and murders, never mind the woozy sunsets and the screaming? You can’t, I suppose, have everything. This selection of Munch portraits takes us from one of his earliest self-portraits (a priggish little oil painting on cardboard, from 1882-3, that has not worn well) to a loose, lithographic crayon profile of British composer Frederick Delius, enjoying a concert while taking a cure (Delius was syphilitic) in Weisbaden in 1922. This exhibition is as much about Munch’s associations, his family and milieu, his collectors and patrons as it is about stylistic or intellectual development. It is all very patchy and uneven.

In 1888, Munch’s elder sister Laura sits gazing out at who knows what, outside a house the family had rented on the coast. She seems to have a very great deal on her mind, as people in Munch’s paintings often do. Suffering mental illness since adolescence, Laura was eventually diagnosed as schizophrenic. Her hands are clasped together, and her gaze and expression fixed, beneath the summer hat planted on her head. It feels an oddly intrusive painting. Even the house behind her feels like it is looking for a way out, sidling off towards the premature vanishing point. A ghostly figure can just about be discerned among the indeterminate smudgy greens that fill the centre of the painting, though I think Munch didn’t mean us to see it. He often painted things out in his early work. But who knows? Munch didn’t seem to know what to do with the landscape, with its low hills, the glimpse of a little inlet, with the man and the woman getting off a small boat. Only Laura’s gaze into the distance matters in this awkward, unconvincing composition.

There’s a lot of family and painting trouble in Munch’s early work, as he found his way in fits and starts in 1880s Kristiania (Norway’s capital wasn’t renamed Oslo until 1925). Here’s the artist’s melancholic, reclusive father, a doctor given to bouts of religious anxiety, looking down and smoking his pipe. And now Munch’s younger brother Andreas, also studying to be a doctor, with a skull grinning up at him from his desk. Andreas was to die from pneumonia soon after his marriage in 1895, while his wife was pregnant.

The same year that Munch painted his rather dutiful portrait of his father, he depicted fellow painter Karl Jensen-Hjell full-length, standing in brown gloom, a flash of light reflecting from his glasses. He’s teetering a bit, cigar in one gloved hand, cane in the other, as though we’ve encountered him a bit worse for drink outside some bar. Later, we meet another of Kristiania’s bohemian stalwarts, Hans Jæger, looking like the sort of bloke you’d detour to avoid as he lounges in the Grand Cafe, affectedly louche in his misshapen trilby and rumpled coat, staring down the painter (and us, while he’s at it) from a sofa.

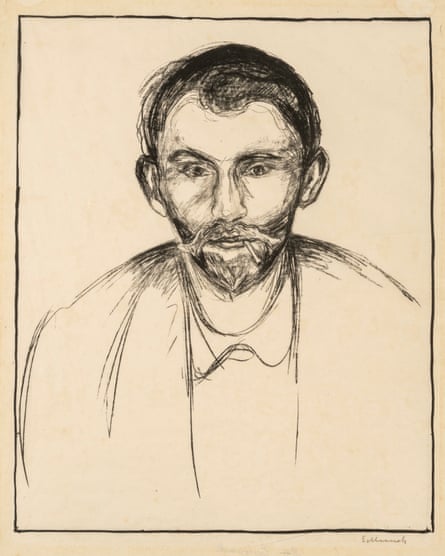

It is difficult to warm to lot of Munch’s subjects. The smug, the arrogant, the faintly creepy. Or very creepy in the case of Polish writer and “rational satanist” Stanislaw Przybyszewski, who, as well as appearing as a disembodied, floating head in Munch’s 1895 painting Jealousy, is depicted here, cigarette in mouth and with a slightly crooked smile, in another of Munch’s lithographs. Przybyszewski married and divorced Norwegian artist Dagny Juel, who had had affairs with both Munch and August Strindberg, and who was murdered in 1901 – in front of her five-year-old son – in Tbilisi in Georgia, possibly as part of a plot devised by her ex-husband.

As soon as a story begins to be told, we are off again. Here’s Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, sister of the philosopher, standing in a voluminous blue outfit, perhaps with a fan in her hands (it is hard to tell – it could just as well be a truncheon). Apparently, Munch kept up a barrage of talk while he was painting Förster-Nietzsche, so he wouldn’t have to listen to her odious antisemitic opinions. He obviously didn’t hate her company that much, as he painted two versions of the portrait.

And now Ludvig Karsten, in a pale suit and wide-brimmed hat, one hand in his pocket, the other holding his pipe, presumably painted before the drunken incident when Karsten threw a bottle at his fellow painter and Munch went and fetched his rifle. We constantly need more detail, and more dirt, especially as Munch dramatised the pair’s fight several times over the years. But all we have here is this fairly anodyne portrait of an entitled young man in a summer suit, some complication simmering away beneath the surface.

In 1909, Munch suffered a breakdown caused by his excessive drinking, and was admitted to a private “nerve clinic” in Copenhagen, run by Dr Daniel Jacobson. Munch painted two full-length portraits of his doctor, standing legs apart, hands on hips, beard trimmed, watch chain in his waistcoat, flouncy cravat at his neck. The painting’s background seethes and roars behind him. Someone took a photograph of Munch and the good doctor standing in front of one of Munch’s two versions of the portrait. What Munch’s painting does not capture, but the photograph does, is Jacobson’s magnificently overbearing posture, his elevated chin, his hauteur. Jacobson reputedly observed “Just look at the picture he has painted of me, it’s stark raving mad!” Which, I suppose, is medical terminology for whatever it was that ailed Munch at the time.

In 1925-6, Munch went on to paint another doctor, Lucien Dedichen, looming over seated art critic Jappe Nilssen, who had championed Munch throughout his career. The dingy, cramped room feels too small to contain the doctor. The painting was once called The Death Sentence, as if it depicted one of those difficult chats in which a doctor delivers an ominous prognosis. As it was, Nilssen lived for another five years, though the longer you look, the smaller the seated man seems to shrink. Years earlier, in 1909, Munch had painted Nilssen in a flaring, cobalt violet suit, standing before a green wall. I have no idea if Nilssen ever owned such a suit, whose colour fizzes and pops with life, the very image of vitality (though Nilssen never liked this portrait, any more than Strindberg liked his, feeling that Munch should have given him the gravity of Goethe. But you get what you get.

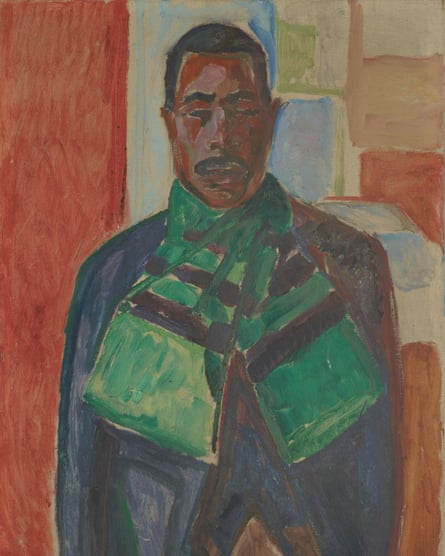

Walking the room where all these portraits hang, we meet symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé and playwright Henrik Ibsen, who told Munch: “Things will go for you as they did for me: the more enemies, the more friends.” It is difficult to know what friends Munch might make here. One portrait in particular stands out. Munch’s 1916 Model With a Green Scarf depicts the artist’s only Black subject, Sultan Abdul Karem, who had arrived in Kristiania as part of a German circus troupe, and was hired by Munch as chauffeur and odd-job man and occasional model. Wrapped in a green scarf, eyes closed, he is the most static of Munch’s models. He is being painted, but there’s no sense that he is engaged, unlike Munch’s other subjects, in any sort of active collaboration with the artist. Apparently, Munch never named Karem in his original title for this portrait.

Writing in the catalogue, Knut Ljøgodt tells us that Karem also appeared in another painting by Munch which was ‘‘given the rather problematic title Cleopatra and the Slave, in which he appears in the nude, standing next to a reclining, naked woman”. There’s a point at which the creepy and the weird stops being entertainment. I have seen enough.

1 month ago

24

1 month ago

24