How do you reckon our political system works? Perhaps something like this. We elect MPs. They vote on bills. If a majority is achieved, the bills becomes law. The law is upheld by the courts. End of story. Well, that’s how it used to work. No longer.

Today, foreign corporations, or the oligarchs who own them, can sue governments for the laws they pass, at offshore tribunals composed of corporate lawyers. The cases are held in secret. Unlike our courts, these tribunals allow no right of appeal or judicial review. You or I cannot take a case to them, nor can our government, or even businesses based in this country. They are open only to corporations based overseas.

If a tribunal determines that a law or policy may compromise the corporation’s projected profits, it can award damages of hundreds of millions, even billions. These sums represent not actual losses, but money the arbitrators decide the company might otherwise have made. The government may have to abandon its policy. It will be discouraged from passing future laws along the same lines, for fear of being sued.

Record numbers of cases are being brought, as corporations learn from each other, and hedge funds finance suits in return for a share of the takings. The result? Sovereignty and democracy are becoming unaffordable.

The process is known as “investor-state dispute settlement” (ISDS). The reason it is allowed to override domestic law and the decisions made by parliaments is that this provision has been written – without public consent, and often in conditions of extreme secrecy – into trade treaties.

A year ago, Friends of the Earth won a great victory at the high court. The judge ruled that plans to dig the first deep coalmine in the UK for 30 years, at Whitehaven in Cumbria, had been unlawfully approved by the Conservative government, which had accepted the bizarre claim that the mine would have no impact on our carbon budgets. The Labour government then withdrew the permission the Tories had granted. Now this victory could be compromised by an offshore tribunal answering to no one but the corporations petitioning it.

In August, a company whose ultimate owners are based in the Cayman Islands lodged a claim against the UK government. Last week a tribunal in Washington DC was set up to hear it.

The company is suing the UK for the money it might have made if the mine had been allowed to go ahead. We have no idea how much this might be. Who is representing it against the British government? The MP for Torridge and Tavistock, and former attorney-general in the Conservative government, that great patriot Geoffrey Cox. The government makes a decision, the high court upholds it, then a foreign company challenges it through an undemocratic offshore tribunal, and a member of our parliament acts on its behalf.

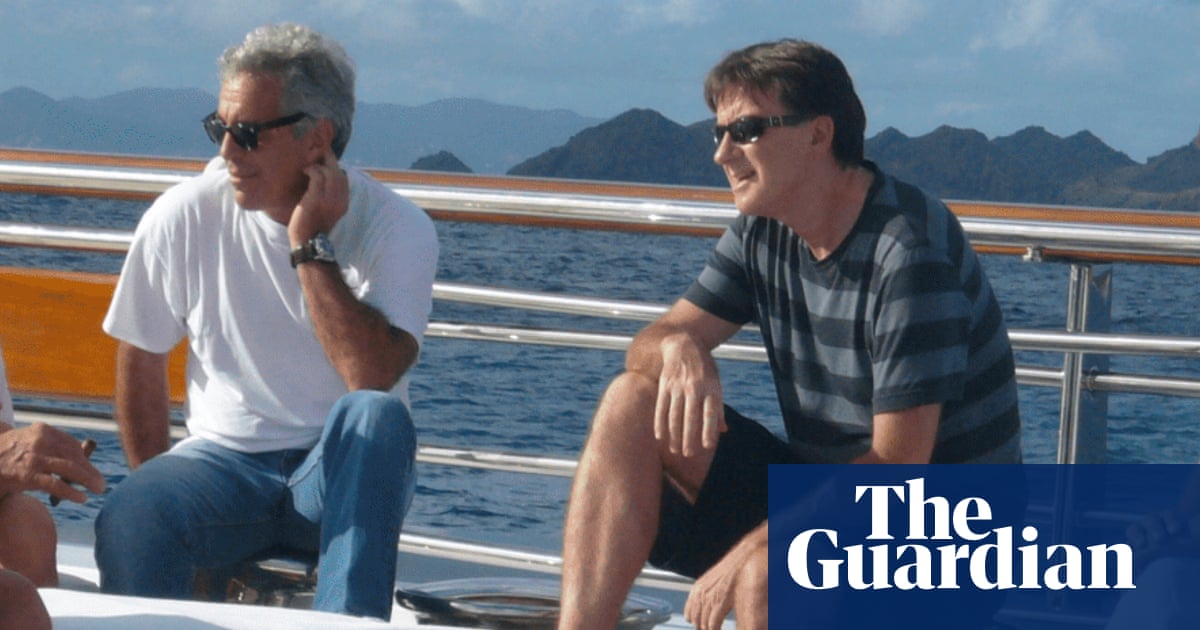

On the same day (18 November) that the tribunal on the coalmine case was appointed, we learned from a parliamentary answer that the UK is also being sued under ISDS by a Russian oligarch, Mikhail Fridman. We know nothing of the case so far, but it seems likely that he’ll use the tribunal to challenge the sanctions the UK levied against him after the invasion of Ukraine. He has already started suing Luxembourg for this reason, demanding $16bn (£12.1bn): half that government’s annual revenue. Among the lawyers representing him there? Cherie Blair, wife of the former British prime minister.

Legal experts believe the EU’s delay in using frozen Russian assets as collateral for its loan to Ukraine arises from Belgium’s fear that it could be sued in the offshore corporate courts, under the Belgium/Luxembourg-Russia bilateral investment treaty. This extraordinary, undemocratic power over elected governments could be blocking the money Ukraine desperately needs.

We were assured that such things wouldn’t happen. In 2014, David Cameron, promoting the biggest and most dangerous of all such treaties, told us: “We’ve signed trade deal after trade deal and there has never been a problem in the past.” The House of Lords adviser on this issue, Prof Dennis Novy, accused campaigners of “scaremongering … in reality, ISDS does not affect the UK much”. The overall message seemed to be that only poorer nations needed to fear these lawsuits. I warned, to general mockery, that “as corporations begin to understand the power they’ve been granted, they will turn their attention from the weak nations to the strong ones”.

That threat has now materialised. This year, fossil fuel and mining firms have lodged a record number of suits against nations rich and poor, challenging – as in the case of the Cumbrian coalmine – government attempts to stop climate breakdown. Corporations have so far won $114bn (£86bn) through ISDS, of which fossil fuel companies have secured $84bn (£64bn). That equates to the combined GDP of the world’s 45 smallest economies. The average payout these companies have received is $1.2bn (£910m). In some cases they threaten to suck the poorest nations dry. This is climate finance in reverse: huge payments to fossil fuel corporations from governments with the temerity to try to stop an existential crisis.

after newsletter promotion

These suits also exert a major chilling effect on governments that would like to go further. France, Denmark and New Zealand have all curbed their climate ambitions for fear of lawsuits, and there are likely many more.

We gain nothing from these treaty provisions. A meta-study in 2020 found that, when it comes to encouraging foreign investment, the “effect of international investment agreements is so small as to be considered zero”. A report commissioned by the UK government in 2013 found that ISDS was “highly unlikely to encourage investment” and was “likely to provide the UK with few or no benefits”.

Yet Keir Starmer’s government shuts its ears. It has reportedly been trying to push an ISDS mechanism into the investment treaty it is negotiating with India, and into the other trade treaties it is working on. We cannot know for sure, because they’re being negotiated in total secrecy. You could almost believe there were things the government didn’t want us to see. It refuses to talk to campaigners or to offer more information.

We have twice beaten attempts to extend ISDS, through vast popular movements against the multilateral agreement on investment and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. Now we will need to mobilise again: this time against our own government, which seems to care more for foreign corporations than it does for us.

-

George Monbiot is a Guardian columnist

2 months ago

63

2 months ago

63