I am a Krapp collector. Since my late teens I’ve returned time and again to Samuel Beckett’s brief but monumental one-act play in which a purple-nosed, “wearish old man” spools through reels of memoir recorded each year on his birthday. Although performed by a single actor, Krapp’s Last Tape is not quite a monologue. It becomes a kind of dialogue between the 69-year-old Krapp and his recorded 39-year-old self, who in turn reflects on how he behaved in his late 20s.

It is, then, a tale of three Krapps. I’ve sailed past two of those ages: next stop, 69! Beckett’s play has endured partly because it bottles the nature of regret – it asks us all to consider what could have happened if we had made other choices in our lives, how things might have turned out differently. Two current productions – starring Gary Oldman at York Theatre Royal and Stephen Rea at the Barbican in London – not only invite audiences to consider such questions but also give the actors a rare opportunity to reconnect with their past.

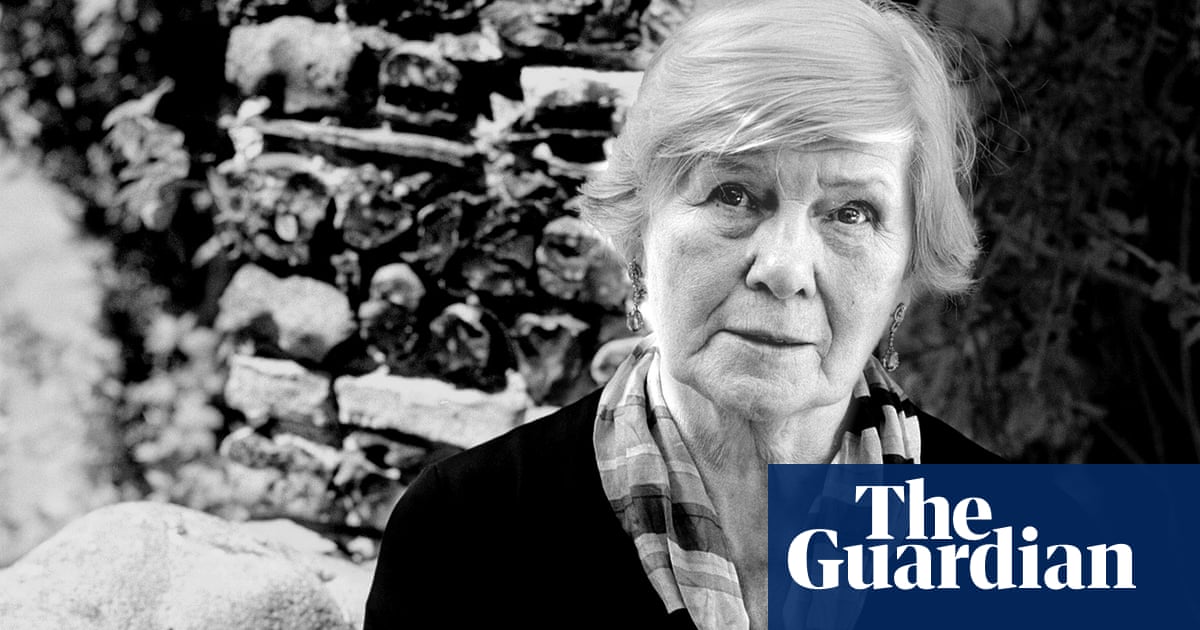

“Perhaps my best years are gone,” says Krapp towards the end of the play. The Crying Game’s Rea, who is 78, disproves any such suggestion with an acutely moving performance, boosted by the use of his own archive recording of the younger Krapp’s lines – done on a whim by the actor in 2009 and stowed away for future use. Rea worked with Beckett on Endgame in 1976 (and did a film of it in 1991) and brings to bear the great writer’s note on that play, “It’s always ambiguous”, with his interpretation of Krapp.

Oscar winner Oldman, at 67, is two years too young for the older Krapp yet seems wearier than Rea as he creaks around the set in York, where he began his career in 1979 and played roles including a pantomime cat. Oldman, who recorded the younger Krapp’s voice in the months before this production, has not acted on stage for 37 years – more than half his lifetime. In a programme note he uses a Krapp-like image to explain theatre’s impact on his screen career, saying he always draws on his “mental museum of theatre references”. The production, which he also directed and designed, honours past Krapps by featuring the same machine used by Michael Gambon and John Hurt in the role.

When I talked to Hurt about his memories of Krapp’s Last Tape, I said I’d seen it in the West End, the year after its 1999 run at the Barbican’s Pit. He instantly replied that he wished I’d seen it in 2013, by which time he had withdrawn the anger from his portrayal. The recording of the younger Krapp that he made for the Barbican run was used for all his subsequent productions. Hurt was similarly critical of that audio performance. However, he acknowledged: “The more I come to dislike what I did on the tape, the more it plays into the hands of the present Krapp.”

In depicting a man who is frustrated – even deflated – by his past, both personally and professionally, Beckett’s play taps into the self-critical actor’s quest for the perfect performance. This gained an unexpected charge on the night I saw Robert Wilson’s thundery expressionist production, featuring immense projections, at the Barbican in 2015. It left me cold, but I was nevertheless shocked when, at the curtain call, a nearby theatregoer was so unimpressed that they booed Wilson, who took his bow seemingly still in character as Krapp, and cast a hurt expression our way.

Rea’s Krapp, directed by Vicky Featherstone, twice looks over his shoulder at the pitch-black that surrounds him, which his younger self says, unconvincingly, makes him feel less alone. The spartan set, designed by Jamie Vartan, is more like a cell than Beckett’s “den” and brings an air of confession or self-interrogation. Krapp’s desk comes with comically deep drawers, concealing his beloved bananas.

Playing Krapp comes with high potassium levels: you usually see this number of bananas eaten by tennis players not actors. Krapp berates himself for tucking into them and keeps the fruit under lock and key – it’s a rigmarole to reach them, much like his system for storing away memories that bring a similarly peculiar mix of pain and pleasure. Rea seems to inhale the scent of his first banana before taking a huge bite that leaves its stringy bits dangling from his lips. Malcolm Rippeth’s sepia lighting for Oldman’s cluttered set evokes a bruised banana; Oldman slings his skins to the floor and gives a sly grin before biting into his second one. Recognising that every sound matters in Beckett, Oldman fills the theatre with the sound of laborious masticating.

Both actors excel at the comedy of Krapp: Rea skittering on and off stage with the reels, Oldman affecting a light and airy voice as he draws out the word “spooool”. When Rea reads from the dictionary a description of the “vidua bird” with its black plumage, the humour is increased by the actor’s own mop of dark curls. Rea turns the memory of a “bony old ghost of a whore” into a cantankerous standup routine, adopting the voice of Fanny, and dourly mocks his younger self. Each actor nails the self-satisfied 39-year-old’s grand proclamation to be at the “crest of the wave”; both emphasise how the older man has not changed as much as he might have wished in the decades since.

Acting is reacting, so they say, and the relationship between the three Krapps is pivotal to the play, as suggested by the on-the-nose choice of We Three (My Echo, My Shadow and Me), a song about being “all alone, living in a memory”, as introductory music for Oldman’s production. His set accentuates the clutter and resembles an attic as he seems to emerge from beneath to potter around boxes, crates and old furniture that form a lifetime of precious detritus. The set, which also suggests he is shored up on an island, even implies a connection between Krapp’s ramshackle belongings and the fragmented scenes and gestures that Beckett wrote for the character.

It’s a play that really needs a much smaller stage than either the Barbican or York’s Theatre Royal. Of all the productions I’ve seen, the venue that suited it best was the subterranean Jermyn Street theatre in London’s West End, which has an impressive record with Beckett. Trevor Nunn directed it there in 2020, in a triple bill with Eh Joe and The Old Tune, recognising that Beckett’s lonely souls gain a haunting collective force when presented together (as in Jermyn Street’s Footfalls and Rockaby the following year). Nevertheless, even the passing references to other characters in Krapp’s Last Tape emphasise its themes – like Old Miss McGlome who sings “songs of her girlhood”.

The first Krapp I saw was soon after reading it at university. That performance was memorable for being halted when an acrid smell wafted off the machine and the theatre’s tech team were called in to investigate. I recall feeling cheated that they resumed at the same point and didn’t do the 50-ish minute play once more from the top. I saw that show with a friend who died at the age of 41 – I now realise that the only tapes I own, boxed away in the attic, are compilations he made for me over the years. I have nothing to play them on, but will always keep them.

A trip to Krapp’s Last Tape in my 20s rekindled a romance that I would come to replay with my own sense of regret. The most striking lines of this singular play – where even the stage directions are longer than the speeches spoken live – are about a breakup. In the 39-year-old’s recording, he recalls it like this: “I said again I thought it was hopeless and no good going on and she agreed, without opening her eyes.” It occurs on a punt on a sun-kissed afternoon, a wretched business tenderly evoked. In Rea’s performance, he perfects the agitated state in which Krapp searches for the section – capturing Hurt’s belief that Krapp is an addict.

Addicted to what, exactly? To a hit not of nostalgia but of emotion – no matter how painful – for a man who has shut himself off. (In a fascinating new documentary, Rea says of Krapp “there’s a very sad life occurring”, that passive verb capturing exactly the loss of control the older Krapp seems to have.) Future Krapp-like characters might be rabbit-holing on Facebook or Instagram instead, grasping for the right photo or phrase to stitch together a memory.

Krapp is a play about memory-making: about stockpiling the moments that define us, not unlike assembling a mix tape or organising your iCloud. It’s what the younger Krapp, an aspiring writer, calls “separating the grain from the husks” – about as good a description as you could use for Beckett’s precision as a playwright. But it is also about self-deception and not facing down the difficult episodes, such as the death of Krapp’s mother.

As you get older, and see new productions of familiar plays, you gravitate towards different characters. The last few times I’ve seen Romeo and Juliet I have been far more interested in the parents than the young lovers. Krapp presents us instead with one man’s range of ages to reflect upon or anticipate. Like Lear, it’s a role that actors and audiences grow into. So it was a masterstroke by Seán Doran, artistic director of Arts Over Borders, to ask Samuel West and Richard Dormer to each record the part of the taped Krapp when they were 39. For the Beckett Biennale in 2036, by which time West will have reached the correct age, he will perform using his recording; two years later, Dormer will do the same with his when he hits 69. (“Extremely early bird tickets” are available now.) This forward planning is fitting. In the opening line, Beckett tells us the play is set in the future – his masterpiece acknowledges the weight of what may lie ahead as well as what has passed.

11 hours ago

12

11 hours ago

12