Columnist at the Guardian US and a contributing editor at the New Republic. He is based in Baltimore

Five years after 2020’s historic wave of racial justice protests, the US is very obviously a country much changed, though not in the ways that activists and reformers had hoped. Many pundits have interpreted Donald Trump’s re-election in November and the culture war he’s waging against the kind of diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives that flourished in response to BLM’s activism as the products of a broad public backlash against the movement’s goals. On DEI in particular, that backlash is not much in evidence – a CBS poll in October, for instance, found 64% of Americans agreeing efforts to promote racial diversity and equality were going either about right or not far enough. But perceptions matter more than realities in politics.

It should be said too that realities on the ground have been disappointing for police reformers lately. While the protests of 2020 led to the drafting of thousands of reform bills in state legislatures across the country, momentum has long since stalled. Civilian oversight boards are struggling to make an impact. Cities that initially cut police budgets wound up increasing funding above pre-protest levels. And federally, a few executive orders aside, hopes for major action fizzled completely under Joe Biden – whose 2020 campaign, researchers have found, was probably aided by the political engagement and shifts in public opinion the protests induced.

We may not see protests of this scale again, but one never knows: 74 unarmed people, mostly people of colour, were killed by US police officers last year. And well beyond killings and confrontations, criminal justice in the US is riven with extraordinary inequities, racial and not, that affect millions. With the right spark or the right case, the country could return its attention to those inequities sooner than we expect.

Journalist and author based in Recife, Brazil

I will never forget when the first protest after the murder of George Floyd was called in my city, Recife, in north-eastern Brazil. A neighbour soon appeared in our building’s WhatsApp group sharing the poster of the call and saying: “Be careful, it will be near the building.” The idea that anti-racist movements are something to be scared of is deeply rooted in Brazilian society.

The killing of Black people has been part of the Brazilian social landscape for centuries. In fact, our infamously lethal police force is a source of pride for many. In São Paulo, the high number of killings in the outskirts of the city is celebrated, and there had been attempts to refuse body cameras on police uniforms. The state governor, Tarcísio de Freitas (Republicans party), a supporter of the former president Jair Bolsonaro, is a likely candidate for president of Brazil. Though he has seemingly reversed his position on body cameras, the thinktank Afrocebrap still warns that Freitas is committed to “the populist notion that ‘a good criminal is a dead criminal’”.

Unfortunately, the record for leftwing administrations is also grim. In the state of Bahia, which has a Workers’ party governor, 752 people were killed in 662 violent incidents involving military police in less than one year in 2023. Another statistic about the Bahian police is even more stark: in that state, of the 616 people killed as a result of military police intervention in 2021, 603 were Black. This number represents 97.9% of the cases. Five years on from Black Lives Matter (BLM), there is little sign of reform or progress – in fact, the US is exacerbating the issue as they provide funding and training to Brazilian police.

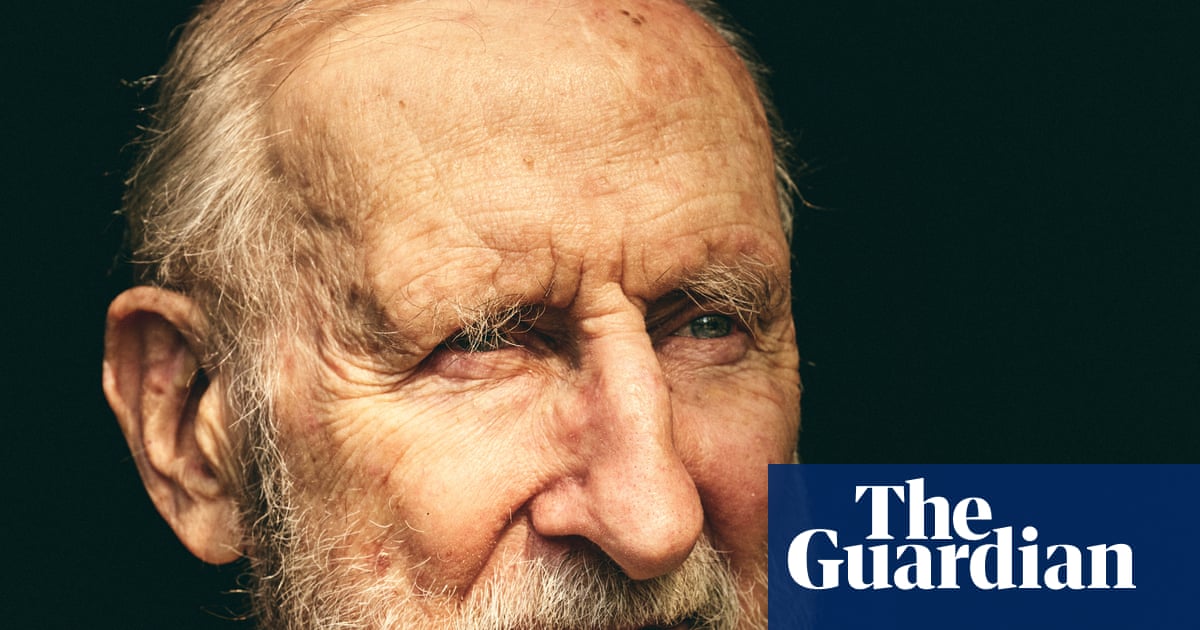

Researcher and writer based in London. He is the author of Black Resistance to British Policing and a member of Black Lives Matter UK

2020 was a hugely significant moment for our movement. BLM UK as an organisation received more than 36,000 individual donations, amounting in total to an incredible £1.2m. We didn’t see this money as “ours” but meant for Black anti-racist struggle in general, so we decided to redistribute 50% of the funds to other groups. It was described as the largest redistribution of funding to Black groups since the 1980s.

This mean £570,000 went towards to dozens of grassroots, Black‑led collectives. This was part of our goal to uplift Black organising both in Britain and internationally. We dedicated the remaining funds towards building a Black-led, antiracist movement that can face the challenges ahead. Some of this key work is represented at our Festival of Collective Liberation, an annual national event in central London, and Project Timbuktu, our Black liberation political education programme.

Hundreds of thousands of people in Britain took to the streets chanting “Black lives matter”, and forced institutions to confront colonial legacies, remove racist symbols and adopt (often imperfect) DEI initiatives. These modest and largely symbolic gains were short-lived, as the growth of anti-immigrant sentiment and recent race riots reveals the tenacity of racism in Britain. The return of Donald Trump and the rise of Reform, in the context of Labour’s austerity economics, declining living standards and the hostile environment, makes antiracist solidarity and resistance more urgent now than ever.

Writer, investigative journalist and podcaster based in Johannesburg, South Africa

In June 2020, South Africans marched through Johannesburg. We had taken to the streets the year before over the rape and murder of 19-year-old Uyinene Mrwetyana, a watershed-moment in our problem with gender-based violence. And we are no stranger to state killings – notably there was the case of Collins Khosa, who was beaten to death by soldiers in Johannesburg during South Africa’s Covid-19 lockdown enforcement. This time, we were marching in solidarity with BLM.

But I noticed something: the US-based BLM organisation and its leaders offered little reciprocal support to our and other African struggles, such as Nigeria’s #EndSars protests against police brutality. It seemed that some Black lives mattered more than others.

BLM’s insularity benefited US corporations more than Black communities worldwide. Brands rushed to declare solidarity, launching DEI initiatives and partnering with prominent Black figures. But their investment in representation didn’t translate into lasting systemic change.

Meanwhile, “digital nomads” fleeing the Trump presidency’s erosion of human rights and DEI gains have flocked to South Africa, driving up the cost of housing and other necessities (conversely, Trump is inviting white Afrikaners to seek “asylum” in the US citing false claims of “white genocide”). Among them are Black Americans who seem to ignore local Black South Africans’ pleas for them to consider the impacts of their “lifestyle neocolonialism”. Wealthy, western Black lives matter most of all.

Multi-disciplinary artist and academic from Trinidad and Tobago

When I sat opposite the US Embassy in Port of Spain after the killing of George Floyd in 2020, I knew why I had been moved to join the protest. It was about recognising the injustice of racism and anti-blackness not just in the US but here in Trinidad and Tobago, where a considerable percentage of Afro-Trinbagonians face disparities in income, education and opportunity, and are victims of extrajudicial killings that are excused by a desensitized wider society.

Trinidad and Tobago has seen few truly meaningful changes regarding the betterment of Black lives and our interactions with state apparatus. There have been amendments to school policy as it pertains to Afro hairstyles. This in a nation where more than 40% of our population is, in fact, of African descent. But our education system remains unequal, and government schools face the scourge of limited resources. The caveat of the new hair policy is that despite the new amendments being ministry policy, enforcement is at each school board’s discretion.

Extrajudicial killings undertaken by the police continue largely unchecked. The Police Complaints Authority continues to fight an uphill battle against “rogue” elements in the service. And the population vacillates between apathy and support for these killings in the face of feeling helpless with regard to white-collar-funded gang violence. There continues to be outcry, however, in impoverished “hot spot” communities where these murders take place. Many times their pain is met with wider public castigation and ridicule.

We now have the further complication of a new government that is extremely sympathetic to Trumpian policy. The United National Congress administration was elected on a manifesto that promised easier access to firearms for citizens and stand-your-ground home invasion laws. These potential developments do not bode well for us, a society with issues of distrust along racial lines.

Chair of Each One Teach One

In Berlin, Black African people have been marching under the banner of Black Lives Matter since the Ferguson unrest of 2014. But 2020 felt like a turning point – the first time that we were joined by a cross-section of German society, to confront this global phenomenon of anti-Black racism. There was a sense that things in Germany might actually change. The German government presented a list of 89 measures to fight racism and extremism. But five years on that change has not come, the measures long forgotten.

In April 2025, a young Afro-German man, Lorenz A, was killed by police in Oldenburg. He was shot at least three times from behind. This has made Afro-diasporic communities feel incredibly vulnerable and unsafe, and the government has said nothing. Even the most basic demand – to refer to a current UN effort to protect the human rights of people of African descent in the new coalition agreement’s priorities – has not been taken up.

Such disappointment has meant that antiracism activists have restrategised. Though we still agitate for change, we are focusing more on building our own institutions and infrastructure to sustain our movement. To take one example: Each One Teach One is a Black empowerment organisation based in Berlin – we recently published the Afrozensus, a data-gathering project that aims to fill in the knowledge gaps about the 1 million people of African origin in Germany. Though the rise of the far right threatens these gains, we are building confidence, and durable empowerment infrastructure not beholden to political moments.

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a response of up to 300 words by email to be considered for publication in our letters section, please click here.

3 months ago

261

3 months ago

261