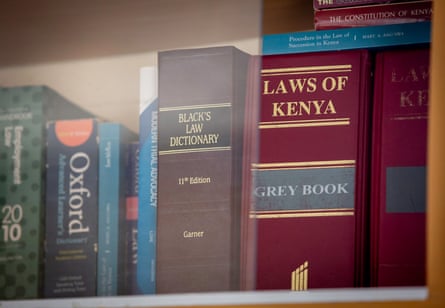

It is a cool, overcast morning in Nairobi, and Ruth Kamande is in front of a computer, deep in concentration. Next to her is a thick red hardback book entitled Laws of Kenya. Kamande, 30, a diminutive figure in a stripy black and white tunic dress, graduated with a University of London LLB law degree in 2024, and works with incarcerated women. Her office, a small light and airy room that she shares with about 10 others, is in Lang’ata maximum security women’s prison where she is serving a life sentence for murder.

“I used to admire lawyers very much,” she says. “It impressed me when I saw them in movies fighting big cases, but also for people in society who are marginalised. I didn’t know that one day, in very difficult and unusual circumstances, I would become one.”

In 2018, Kamande was sentenced to death after a court found she had stabbed her boyfriend, Farid Mohammed, 25 times at the home they shared in Nairobi in September 2015. The case was widely covered by the press in Kenya and abroad, and on social media. People expressed horror, shock and disbelief; how could such a softly spoken, petite and pretty 21-year-old woman commit such a brutal murder?

-

Kamande, a prisoner at Lang’ata maximum-security women’s prison in Kenya, has successfully helped other incarcerated women win cases

Kamande won’t talk in detail about what led her to stab Mohammed, 24, nor will she talk much about the events of that day. She has hopes of representing herself at a retrial, and doesn’t want to jeopardise chances of that happening.

The death penalty exists in Kenya for offences such as murder, robbery with violence and treason, though there have been no executions since 1987. Kamande’s sentence was changed to life imprisonment in 2023 as part of a broader commutation of death penalties in Kenya. As things stand, she will spend the rest of her life behind bars.

At trial, Kamande told the court she had acted in self-defence after discovering Mohammed’s HIV-positive status. After her conviction she filed an appeal but that was dismissed in 2020.

“Truth be told, I realised I was wrong,” she says. “It’s not good to take away someone’s life. Though I have my own reasons, and at that moment I felt so threatened and I was so afraid. I felt like it was my life which could have been taken instead. Everyone fights for their life. Even right now, if I stand and hold a knife at you, what would you do? You will defend yourself, but later on you will also say ‘maybe I shouldn’t have done that’.”

-

Kamande at her graduation ceremony in November 2024. She uses her law education to help herself and other women in prison.

In 2023, she appealed to the supreme court, asking whether she could defend herself on the grounds of battered woman syndrome, a psychological condition of individuals who have endured prolonged and severe abuse at the hands of an intimate partner. The appeal was dismissed in April 2025.

It was a desire to understand her own case that first pushed Kamande towards the legal system. Justice Defenders, a non-profit organisation working in prisons in Kenya, Uganda and the Gambia, held sessions on legal rights and one day in 2016, a representative announced he was recruiting people to become paralegals.

“That’s when I decided, ‘OK, let me try this, because I need that basic knowledge to help myself,’” she says. “I felt that my lawyers were not listening to me and I didn’t know anything concerning law. I was not in a position to convince them and tell them ‘this is what you have to do’. I was craving help.”

She began learning about the constitution of Kenya. At the same time, she realised that most of the women she was with in the remand section of Lang’ata women’s prison could not afford lawyers. She says: “I felt that if I had representation and was still anxious, how about this person who does not have a lawyer?”

In Kenya, 19,387 women are in jail, 9% of the prison population, according to the latest figures from Kenya’s National Bureau of Statistics. (Other sources say the numbers are as low as 5% but they may not include women on remand.) What is not in doubt is that numbers are increasing; in 2024 the daily average number of women in prison was 4,592, up from 2,915 in 2023. Most are arrested for petty offences under laws that criminalise poverty and penalise acts of survival such as hawking or brewing illegal alcohol. Unable to pay for legal representation or bail, they are kept in pretrial detention for long periods.

-

Justice Defenders, which enabled Kamande to receive an education in law, work with prisons in Kenya, the Gambia and Uganda (pictured).

“I started helping them,” says Kamande. “Trying to go through court statements with them, understanding their case and drafting cross-examinations. I would tell them the questions to ask witnesses and help write submissions [outlining legal arguments]. That’s how I began.”

The first woman she helped was acquitted for the crime of obtaining money under false pretences and from then on, Kamande was hooked. “It felt good,” she says. “And it gave me the zeal and morale to continue.”

There have been many other successes since, and she smiles as she recounts the time she requested free bail for one woman in prison and it was granted.

Kamande is cagey about her life before prison. She says she was brought up in Nairobi by a biological mother and a “foster” one. She has two brothers; one of their names is spelled out on a bracelet she wears. She loves football and used to play in a team at school as a defender. She met Mohammed at a friend’s party when she was 19, shortly after finishing school. She says she was close with his family. When she was arrested, she was working in telemarketing after having deferred her university studies in business information.

In prison, she reads – her favourite author is John Grisham, known for bestselling legal thrillers. She attends classes and writes; she wants to publish an anthology of her poems. She prays every morning.

She says she regrets what she did and, in 2017, contacted Mohammed’s family. “I realised I should go back to the family and seek forgiveness and explain my side of the story,” she says. At first, the family refused. “They were still grieving and I understood,” she says. But then, in 2021, Mohammed’s mother called the prison. She told Kamande she had forgiven her and that she should continue living her life. “I really cried,” says Kamande. “They deserved to be told sorry, like I know you cannot bring back life but at least just trying to accept your mistake and requesting forgiveness can heal a part of someone’s grieving.” Kamande receives visits from some of Mohammed’s relatives.

Lang’ata’s large gates are staffed by a small group of armed guards. Pass through them and a shop on the left sells arts and crafts made by prisoners. The odd warthog and sheep wander the grounds, which also house the remand prison and staff accommodation. The main prison is on the right: large dark-green iron gates with a horizontal strip across the middle in black, yellow and red (the colours of the Kenyan flag) have a small door. Directly outside is a flowerbed spelling out “Lang’ata max security” in brown and green shrubs.

-

Lang’ata is the only maximum security women’s prison in Kenya.

This is the only maximum-security women’s prison in Kenya. In charge is Fairbain Ombeva, wearing pink lipstick, her cropped hair highlighted with blond frosted tips. “We try to make it as homely and friendly as possible,” she says. “I like to call it Lang’ata girls high school, a palace of correction.” Rehabilitation is key she says, and points to the whiteboard on the wall with a list of programmes and activities on offer. On the first day the Guardian visits, she says there are 659 women and 39 children held here; under Kenyan law, children up to the age of four can stay with their mothers.

Inside the gates, manicured lawns and flower beds line concrete walkways, tended by prisoners watched over by guards. Large parts of the floor are covered with circular patterned tiles in creams, browns and grey.

On site is a counselling room, classrooms, an area called “industry” which is thronging with the noise of chatter, looms and sewing machines. There is also a bakery and library, funded by private foundations.

During their downtime, women mill about outside. They sit together and talk, do each other’s hair, or knit and sew. Today, Afropop is blaring from speakers and three women strut up and down, practising for the Miss Lang’ata beauty pageant. Kamande was crowned Miss Lang’ata in 2016.

Women sleep in dormitories called “wards”. Kamande is in ward 12, home to 45 women. Two rows of bunk beds face each other across a narrow corridor. The walls are painted cream, the ceiling is wooden; a calendar with pictures of the former pope hangs from the wall and there’s a television in the corner.

There are more intimidating areas of the prison where officers carry batons, and also one room rammed with beds where nine women nurse their newborn babies. One section holds women who owe money for up to six months, against international standards. Two women on death row are held in a dark, bare and gloomy cell block, with narrow slits for windows.

The cell where new arrivals spend their first night has a curtained off toilet and shower. There are four beds, some without mattresses. Up to 30 women can arrive in a day, according to one officer. What if more come that can’t fit in the room? There are never too many, comes the answer. In a storeroom on site is a shelf lined with black helmets with visors for when riots happen, which the Guardian is told are “rare”.

-

‘When you are convicted, it’s so easy for you to decide not to do anything,’ says Kamande

While two previous inmates at Lang’ata told stories of severe overcrowding and beatings from staff, Kamande has no complaints. On the two occasions the Guardian visited the prison, it was with the permission of Ombeva and in the presence of at least two officers.

When Kamande first arrived, her death sentence meant she was not allowed to interact with others and had to be accompanied by a guard at all times. “That tight security can destabilise your emotions and even how you think,” she says. “I was overwhelmed and at times I would space out. I would wonder why everything I did [in terms of my court case and appeals] failed.”

There was one officer, Madame Jackie, who Kamande credits for turning her life around. She pushed Kamande to attend anger management classes and counselling sessions, and then to study for her law degree, offered by Justice Defenders. She urged her to take any opportunity that came. “She would remind me that it’s not all about myself. She said, ‘It’s true you are suffering because of what happened, but you can use this milestone to help someone else’.”

Kamande enrolled on the course in 2019. She credits prison officers for making sure she attended classes. She completed her studies in 2022 and at her graduation ceremony in November 2024, she was valedictorian.

Today, she applies her education to her own situation. “I understand my case better,” she says. “I feel like so many things have been overlooked. So many things have been left out.”

She has recently joined a working group to advocate for reforms, question policies and identify gaps in the law. She wants to push for a definite term for a life sentence and conditions for parole, among other things.

“Prison is to rehabilitate, it’s not to destroy,” she says. “At the moment, when you sentence someone to life, are you rehabilitating the person or are you destroying them?”

-

Kamande credits prison officers like Christine Wairimu, pictured, for making sure she attended classes during her law degree

2 months ago

63

2 months ago

63