When I first discovered chess, after watching the movie Searching for Bobby Fischer on HBO, I was a nine-year-old kid living in a tiny village in the mountains of Arizona. Because of its title, many people think the film is about Bobby Fischer, the reclusive chess genius who bested the Soviet Union in 1972, defeating Boris Spassky to become the first US-born world chess champion in history. Really, it’s about how the American chess world was desperate to find the next Bobby Fischer after the first one disappeared. The story follows Josh Waitzkin, a kid from Greenwich Village in New York, who sits down at a chess board with a bunch of homeless dudes in the park one day and miraculously discovers that he’s a child prodigy – at least that is the Hollywood version of the story.

Searching for Bobby Fischer was to me what Star Wars was for kids a few years older. I didn’t simply love the movie. I was obsessed with it. Any kid who’s ever felt lost or misunderstood or stuck in the middle of nowhere has dreamed of picking up a lightsaber and discovering the Jedi master within. That was me in the summer of 1995, only with chess.

I was dirt poor. Tonto Village, where my sister, my brother and I lived, had nothing but dirt roads, and we’d run around barefoot most of the time. We’d disappear in the forest for hours, playing cops and robbers, building magnificent forts, making our own worlds. For most children, the challenge of living in such a small, remote place would be loneliness, only having a handful of others like yourself to play with.

But that was never the case in Tonto Village. On any given summer day, there were probably around 100 of us, all under the age of 12, running around shirtless and barefoot in the dusty streets and hills and streams and forests, because we were all being raised in the Church of Immortal Consciousness – a cult.

My mother was a lost soul, and it was because of her wayward spiritual wanderings that we ended up in the Church of Immortal Consciousness – which was known internally as the Collective, or the Family. It originated with the teachings of Dr Pahlvon Duran, who lived his last lifetime as an Englishman in the 15th century. But Duran’s teachings had not been passed down to us in stone tablets or through some ancient text. They were channelled through a trance medium named Trina Kamp who was first visited by the spirit of Duran when she was nine years old.

In the Church of Immortal Consciousness, run by Trina and her svengali husband/manager, Steven Kamp, we were taught that “there is no death and there are no dead”. Your soul inhabited a body so that it could learn lessons. You’ve had many lifetimes, and you may have many more lifetimes to come. Finding and fulfilling your “purpose” was of the greatest importance, and before you could achieve it you had to live a morally upright life. Integrity was the key concept. If you succeeded in keeping your word and being a good person, you were said to be “in integrity”. If you failed, you were said to be “out of integrity”, which was considered the gravest of sins in the Collective.

Finding your purpose was in part about what you were meant to achieve in life as an individual, but it was also about the life you would pursue together with a partner in raising a family. Finding the right partner meant finding your “like vibration”. A like vibration is an energy, an electric, pulsating vibration emanating from the centre of the universe and living inside us. Sharing a like vibration basically meant having a healthy marriage, and a common vision about how to raise children and handle money. If your marriage was struggling, often the validity of your like vibration was brought into question.

Steven and Trina’s followers were drawn to Duran because they were in need of real help. Many of them – alcoholics, drug addicts, abuse survivors – were running away from their families and from themselves. They had a hole in their lives that they needed to fill, and in order to fill it they gave themselves over to a thing that offered them answers. Which is how a tiny, remote village in the middle of a national forest became home to a bunch of damaged people, desperate for help.

And that’s where my mom, Deborah Lynn Sampson, and dad, Steve Rensch, entered the picture. From what I’ve been able to piece together, my parents’ marriage was still somewhat happy and mostly intact when they decided to join; at the first Collective Halloween party they attended, my mom went as Barbie and my dad as Ken, and I’m told they had a great time. But it wouldn’t take long for the cracks in their marriage to reveal themselves, becoming fissures and then canyons.

While it had originally been my mother’s idea to join the Collective, my father soon became the far more devoted adherent, throwing himself into the service of Duran and, by extension, Steven and Trina. My dad eventually became an ordained minister in the church, as well as Kamp’s chief lieutenant and right-hand man. As my father’s stature rose, their marriage fell apart. Less than six weeks after I was born, my 38-year-old father announced he was leaving my mother. Only he wasn’t leaving her to be with the other woman he had impregnated while married to my mom. Instead, he planned to marry Steven and Trina’s daughter Marlow, who was all of 19 years old.

Marrying the daughter of Steven and Trina Kamp, and becoming stepfather to her one-year-old son, my stepbrother Dallas, solidified my father’s position as a man of status and power. As his star rose, my mother’s plummeted. She was now the first wife, a scarlet woman, a person of no importance. For a time she was even “de-merged” from the Collective. They asked her to leave, which she did, when I was five. Our family, now with my younger brother Josh and mom’s new husband, Dennis, moved to Colorado. You might think this would have driven her to despise and reject the Collective for ever, but, in fact, in the long run it did the opposite. When Steven Kamp invited her back a year later, she returned and, after some initial reluctance, decided she was ready to work that much harder to prove her worth to this group in which her ex-husband now served as pastor.

When we moved back to the village, I was tarnished like my mom. I was the bastard child of Steve Rensch, the living evidence of his failure to have a like vibration marriage with my mother. I barely knew my father. I didn’t even know he was my father until I was seven years old, nearly two years after returning from Colorado. His paternity wasn’t acknowledged to me by anyone, including my mother – in spite of the fact that he lived right around the corner from me in a village of only a few hundred people, all of whom knew full well that I was his child.

I probably had a vague sense that Dennis Gordon, a mechanic, hadn’t always been my father, but as he’d been raising me since I was four years old I was too young to interrogate what those feelings were. I wasn’t Danny Rensch. I was Danny Gordon, and I didn’t question it. Then, one day, Steve and Marlow asked their daughter Bean if she had a crush on anybody. Bean said that she had a crush on me. That’s when they realised they had to tell everyone that Bean and I were actually half-sister and brother because her dad was my dad.

If it all sounds a bit incestuous, that’s because it was. Because any kind of collective ultimately is. Nobody owned or possessed anything . Adherence to Duran’s teachings was a greater priority than having material things – and the most important thing was finding your purpose.

In the village, nothing belonged to you. Everyone’s assets were “merged”, a term that was not chosen by accident. The whole idea was to let go of the material world and give yourself over to the spiritual journey of achieving your highest self. It was essentially communism. Glenn, who was basically my godmother, used to tell the story of the day she showed up with her husband, Jim. They pulled up in a U-Haul, parked, and the moment they opened up the back of the truck, people showed up and started taking things. The village was littered with bikes, because nobody actually owned them. If you needed to go to another kid’s house and you saw a bike, you took it. Then when you came back out to go home, the bike would often be gone because someone else had swiped it.

In the Collective, your money didn’t belong to you, either. Duran’s teaching was that “money is God in circulation”, meaning that it needed to flow freely in order to be equally shared. But no matter where the money came from, it all flowed into a single set of bank accounts that were overseen by the leaders of the Collective.

For years we were told of a mythical “shoe list”. If you needed shoes, you’d go to your mom and ask for shoes and she’d say: “Well, I’ll try to get your name on the shoe list and we’ll see how fast you move up.” But it turned out that there was no shoe list. It was conjured up to cover for the fact that there wasn’t any money for shoes. Kids only got to visit the store and get new shoes when they had to go to the doctor or make some other “public appearance”. Most of the time, we simply didn’t go to the doctor. Or the dentist. The whole concept of going to a dentist for a cleaning and a checkup was alien to us. You went to the dentist when your tooth hurt, and that was it.

Families were moved around between different houses all the time. We were told where to go by Steven and Trina. Between the ages of six and 12, I probably lived in eight different houses. I spent most of my childhood sharing bedrooms with anything from five to 10 kids who weren’t related in any way to me. Sometimes we had to share bathwater, too.

Every cult is built on a hierarchy of status and power. In the spiritual hierarchy of the Collective, my mother and I were at or near the bottom, which was horrible for her but wonderful for me. Because it meant I was free. When you’re that young, regardless of your circumstances, you’re basically happy because you take the world as it is. I was just this dirt-poor village rat, building forts and playing cops and robbers and running away from mountain lions and having the most amazing childhood you could imagine. Other than my mom, nobody knew about me, nobody cared about me, and nobody wanted anything from me. Then Steven Kamp discovered that I could play chess.

After I watched Searching for Bobby Fischer on HBO, the rest of that summer was chess, chess, chess, and more chess. Across the village, my stepbrother Dallas had also watched the movie and become obsessed with chess. We found one of those red‑and-black Mattel chess and checkers sets, the ones you get at Walmart, and we played for hours every day, even practising speed chess by putting a book next to the board and hitting it after every turn, the same way the characters in the movie would hit the clock while playing blitz in Washington Square Park in New York City. One afternoon, out of nowhere, Dallas said: “Hey, why don’t you come with me and play chess with my grandpa?”

By grandpa, he meant Steven Kamp. For Dallas to go to Kamp’s was no big deal, but I was immediately terrified; I’d only had a handful of face-to-face interactions with this powerful figure who sat on high. Still, I went along, and from the moment I walked in the door I was overwhelmed. There was an energy to the place, in no small part because it was the Kamps’ house. While everyone else was living with three or four families under one roof, the Kamps lived alone.

Kamp had a genuine passion for chess. He’d been taught by his father, owned lots of books on the game, loved to play, and was a decent player compared with most. The whole experience was surreal. I can remember being in the kitchen later that day and thinking: “Oh my God. They have Cheerios.” While everyone else was living on food stamps, Kamp had cigars and stacks of Cigar Aficionado magazines. It didn’t upset me. I thought it was cool, and the smell of cigars added to his mystique. He had nice things that others didn’t, and that was how it was supposed to be.

Through September and into the fall, Dallas and I were regularly invited over to play. Kamp was way stronger than us at first, and he gave us a proper introduction to the game. He shared his chess books with us, showed us strategies and moves, taught us how to read descriptive notation, and how to say cool things such as “pawn to queen’s bishop 5”.

By October, Kamp was excited enough about our progress to start looking for a tournament we could play in. As it happened, the Copper State Open was right around the corner, so he signed us up. I found out about it on my birthday. On the morning of 10 October, I opened my presents from Dennis and my mom. They got me a tournament chess set, the one with a vinyl board that you roll up like wrapping paper and store in a bag that has a zipper, two pockets for pieces, and a pocket in the middle for a clock. They got me the clock, too, the kind you see in the movies, where the players bang down on the brass buttons after every play. It was the best birthday ever.

The day of the tournament was a blur because I was absolutely out of my mind with nerves the entire time. I couldn’t think straight. I gave up one winning position after another and ended up going 0-5 (zero wins, five losses). Hardly a great start. Dallas, being a year older and more mature, went 4-1 (four wins, one loss). Kamp had promised to pay us five bucks for every game we won, so Dallas got $20 and I got nothing.

At my local elementary school, the Shelby school, the following Monday, the other kids teased me mercilessly for losing so badly, so much so that I ran home in tears at recess. Later that evening, my mom sat me down and told me that she’d spoken to Kamp. “Honey,” she said, “we talked to Uncle Steven, and he says that even though Dallas won more games, he could tell you have a knack for it. He could see how much you care. And he could see you have a gift for the game.” Hearing those words felt so good. Here was this powerful man saying he believed in me, and if he believed in me that meant I could believe in myself.

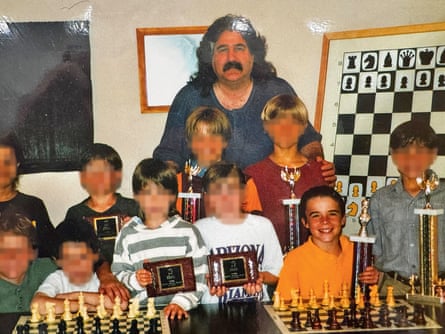

After seeing the potential Dallas and I showed in that first tournament, Kamp declared: “We’re starting a chess team at the Shelby school. Let’s see how many other kids want to play.” And because Kamp was the man who could make anything happen, it happened. Anything we needed to be better at chess, we got. In short order, we even had our own van, a big white one that we called The Whale, and there was always a parent on call to drive us to tournaments. All through that winter and spring, we played tournament after tournament. We destroyed everyone. The Shelby school chess team was taking names and turning heads, and it wasn’t long before people started wondering how this little school from northern Arizona could get so good, so fast.

In the Collective, attending a trance with Duran was the equivalent of going to church in a more traditional denomination. Once a week, we’d gather on rows of folding chairs in a hushed room, the floors carpeted, the windows blacked out, the room dimly lit by a few red‑hued lightbulbs, which was the optimal environment for Trina to trance. She’d sit facing us in a big, comfy wingback armchair.

Trances could get heavy if Duran’s lecture was intense. Sometimes, a sermon targeted the broader failings of the group, or was directed at individual members, focusing on sensitive topics directly affecting them. People were encouraged to bare their souls and ask questions about their marriages, or their relationships with each other or their parents or their kids.

One evening, not long after I had turned 12, at a typical Sunday trance circle for young members, the subject of the chess team and my performance came up. Duran turned to me and, in his raspy whisper, said: “Chess is your purpose, Danny. And you will accept chess as your purpose.” It came out of nowhere. It wasn’t like an anointment. I was not being knighted by the queen. It was said more as a spiritual correction or chastisement, a reminder to stay the course, to not be distracted, to not stray from God’s path.

Duran’s words were picked up and repeated by everyone in the weeks and months that followed, by my teachers and coaches, my parents and Kamp – always as a reminder to practise more and work harder: “Chess is your purpose, Danny. Remember that.” I had been given a purpose by God, a blessing, which meant I now had a duty and responsibility to live up to it, and from that moment on my life started to change dramatically.

That fall, I got my own dedicated, full-time chess coach: Igor Ivanov, the infamous Russian defector of the Arizona chess scene. Kamp hired him. Ostensibly, Igor was there to coach all the Shelby school kids, and he did, but working with me quickly became his full‑time job, and working with him became mine.

This purpose I’d been given by Duran, this gift that had filled me with such joy and self-worth, began revealing its downsides. Any time I was struggling, or if I was spending too much time being a kid and playing basketball with my friends, Duran would declare that it was because I wasn’t committing myself to my purpose. “Danny, you’re in your ego,” Duran would say. “You need to be committing more time to your purpose and less time to other things. Don’t forsake the gift that was given to you. You are given your gifts, and then you earn them.”

after newsletter promotion

That was a phrase I heard often: I had been given the gift of knowing my purpose, and now I needed to earn it. So I did. For the most part. But if I ever struggled at all, had a bad tournament or lost too many rating points, that meant somebody wasn’t being spiritual enough, which meant it was time for a “process”. In a process, members would confess their trespasses, fears, inadequacies, failings and weaknesses, as well as their judgments on others, so the assigned minister and the group could help them find their way back to being in integrity. These ideas – along with the golden rule, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you” – made up the core teachings of the church.

One day, my mom, Debby, and her husband, Dennis, were called into a process with Steven and Trina Kamp, who told them that Debby wasn’t doing a good enough job taking care of me so that I could play chess. After the process, Debby and Dennis got home late, about 10.30pm, and by that point my mom was completely shitfaced. She sat me down at the table and stumbled into the kitchen and turned on the stove and started going through the fridge and cabinets, saying: “Danny, they told me you’re too skinny. I need to put some more meat on your bones.” She pulled out some ground beef and went to the stove and started drunkenly making a hamburger. She continued to talk, saying things that felt rehearsed: “I’m not feeding you enough. I’m not taking care of you. Aunt Trina wants you to be healthier and stronger! Like her!”

It was late and I was tired and I wasn’t even hungry. But she dropped this burger down in front of me on a plate and started telling me she loved me and we’d get through this. Meanwhile, Dennis sat there at the table next to us, not saying anything, head down, clearly festering and angry.

To this day, I can still feel the pit that I had in my stomach as I struggled to eat a few small bites of the burger before saying I didn’t want any more. She made me keep eating it, but I kept saying I wanted to go to sleep. Eventually, she gave up because she was too drunk and tired to keep pushing me. I went to bed but didn’t sleep.

Sure enough, the next day the other shoe dropped. My mom came home from another process with Steven and Trina and said: “Uncle Steven says it’s time for you to take a break from chess.”

“Taking a break from chess” didn’t mean that I was completely off the team, at least not right away. I wasn’t allowed to play in tournaments, but I was still taking lessons with Igor, and chess was still, technically, my purpose. But it was immediately clear that something had been set in motion, and that Kamp was calling the shots.

“What you’re doing in chess,” Kamp told me, again and again, “is greater and more important to the spirit than anything or anybody here. And with everything that’s going to be on your plate, I don’t know that Debby and Dennis are up to snuff in terms of everything you need. I’m working on it! Trying to help them! But stay close to me, and we’ll figure this out.”

Over the course of that summer, I continued to have more talks with Kamp in which he gently, reassuringly and very kindly began to alienate me from my mother and stepfather. What started out as “Debby and Dennis are good parents but maybe just aren’t up to snuff” quickly turned into: “Let’s talk about your relationship with your mother. It’s troubling. It’s like your mom is married to you, and that’s inappropriate. And, who knows, maybe she’s attached to you because she also knows you weren’t actually meant to be her kid after all? I remember when you came in there were lots of questions about that! Your mom was sick, you were passed around, lots of women took care of you, and people didn’t know who you were meant to be with. I’m just saying … maybe it’s time for you to be open to that possibility.”

The removal from my mom and stepdad started off with a bang: I went on a tear, gaining a ton of United States Chess Federation rating points and becoming the youngest national master in Arizona history. Steven was elated, and it was all the evidence he needed to justify turning the “fly the coop” experiment of a few months away from home into a permanent separation from my mother. It would be more than 10 years before I would reunite with my mom.

As an orphaned “cult kid”, people helped me travel to compete in chess tournaments, but often everything else about my mental, physical and emotional needs went overlooked. My hopes and dreams of being a professional chess player crashed and burned in my late teens when I lost all hearing after both my ear canals collapsed suddenly on a plane ride home from the US junior chess championship in Kansas. It turned out that years of neglected ear infections had led to a benign growth of scar tissue that had surrounded, and now collapsed under the cabin pressure, the stapes bones and canals in each ear. I was now permanently grounded, right at the time where the chess world began to go online.

I was stuck in bed in Arizona, stone deaf and dead broke. Miraculously, my fiancee, Shauna, who also grew up in the Collective, stuck by me through the ear surgeries, even as my drinking got worse, and even as it looked like my whole life might implode. In order to be in integrity and to live together with purpose, we were being pressured to take our relationship to the next level. So, during the brief window of relative good health I had between my surgeries, we started trying, and Shauna got pregnant almost immediately with our first-born son, Nash. Despite the frustrations I had about not being able to travel and compete, Shauna saw this opportunity for what it was, and she pushed me to lean into my new role working at Chess.com and to be on board with the vision of what the website could become. Kamp, however, was growing less enthusiastic about my potential as a top player, and therefore slowly less invested in me as a person, once he saw my focus shifting away from playing chess and more toward building an online chess community and business.

In the Hollywood version of leaving a cult, the victim of the nefarious leader typically comes to some sudden epiphany about the ways they’ve been abused, and then they begin what feels like a daring, high‑stakes prison escape. Or their friends and family stage an intervention, hatch some type of secret midnight kidnapping of their loved one and drive away before they get caught. That wasn’t my experience.

The reality is that it takes years and, morally speaking, it’s a murky and grey experience. Ultimately, the glue that holds a cult together is not the abuse and exploitation that comes from the top. It’s the abuse and exploitation that the members inflict on each other. In a cult, the victims are the perpetrators, and the perpetrators are the victims. So, in the end, leaving is not about breaking free of your abuser’s control. It’s about reckoning with your own complicity in the abuse and exploitation that took place.

Not long after Shauna and I left Tonto Village, around October 2021, Steven and Trina Kamp finally went completely broke. They tried to sell off the Shelby school building and the Collective’s communal property to claw their way out of it, which they had the legal right to do; everything was in their name. But the Collective had paid for all of it, so people were properly furious. Everyone in the village started tearing each other apart, fighting over the scraps of what was left, and the whole thing turned into a circular firing squad, which I suppose was what the Collective was always destined to become.

The Church of Immortal Consciousness never had any big, bloody moments like Waco or Jonestown, but the damage it did to its victims, in the long run, was severe. In the wake of the Collective’s implosion, an entire generation of young people scattered out across the south-west and the rest of the country, all of us struggling to make sense of how we grew up. Some of us are doing better than others, but we are all damaged by our experience.

It is impossible to deny that Steven and Trina Kamp and Duran were, together, the architects of most of my pain. They were the ones who had filled me with this notion that being a child prodigy was my purpose, that if I failed to become a grandmaster I had failed on my divinely ordained mission. By inculcating that single-minded – and, frankly, unattainable – ambition in me, they had saddled me with a decade of anxiety, self‑loathing and fear.

They had also made me – or at least encouraged me to make myself – into a cold, domineering, self-righteous asshole. In my conscious mind, I was the best husband and father that I could be, but really I was largely self‑absorbed. I was still gunning for the international master and grandmaster rankings that I was so sure I deserved.

When I was working myself to the bone running my own business and making content for Chess.com, my personal motives were still focused on proving to everybody that I was the man. I can see with hindsight how totally self-consumed I still was. I was falling far short of being a good dad and, especially, a good husband.

The truth is that Shauna and I were still struggling because I lacked respect for women. I’d grown up in a toxic patriarchy in which men could discard their wives without any real consequences or accountability. Like every young man being raised in the Family, I’d been taught to see women as a means to a man’s spiritual ends. I was holding on to Shauna for dear life; she was the only anchor I had in this storm. But my attitudes mirrored what I’d been taught and what I’d seen other men do my whole life: “If this marriage isn’t working out to serve my needs, if Shauna is going to be an impediment to my spiritual growth, then maybe I’ll have to move on.”

During her pregnancy with our third child, Hazel, Shauna and I had one long, drawn-out fight that finally brought me to my senses. It was about our marriage, the Collective, chess – just about everything. Shauna wasn’t someone who yelled very often, but that night, after hours of arguing, she finally snapped and screamed: “Your purpose is not chess! Your purpose is not anything you do! Your purpose is just to be you. Your purpose is us. It’s me and you. It’s raising our kids. Chess is just what you do if you’re enjoying it, if it helps people, whatever. But your purpose is what you choose to do, and you don’t only have purpose on the planet if you become a grandmaster.”

It took balls to say that, because she was not only repudiating the entire philosophy of Duran and the Collective, she was aiming right at my sense of my own self. I’m sure she’d made some variation on that argument a dozen times before, but on that night, for whatever reason, I finally opened up and listened to her, and it broke me. I realised I had deeply confused the difference between having purpose in what you do and making my purpose a “goal”. And, in doing so, I had made everyone in my life just a means to achieving that goal. I cried hard that night. All the heartbreak and tears of being a failed child prodigy washed over me. I finally realised what a terrible husband I had been, so obsessed with myself and what I thought was my purpose that I couldn’t see my own wife, except as supporting me in the pursuit of it.

The big lie at the heart of the Collective was that everyone’s purpose, ordained by Duran, was your special reason for being in this world, whether it was chess or sports or ballet or fixing cars. Your purpose was always something you did, and the doing of the thing, achieving perfection in the thing, was what gave you fulfilment in life, and you would keep living your lifetimes over and over again until you achieved that perfection. But that’s wrong.

What I learned, and have tried to practise from that day forward, is that your purpose is not something you do or a goal you achieve. It’s the reason why you do the thing, not the thing itself. And the principal reason why we do anything in this world should always be to help something greater than ourselves. To serve others, to bring joy.

Danny Rensch is a co-founder of Chess.com, and the platform’s chief chess officer

1 month ago

46

1 month ago

46