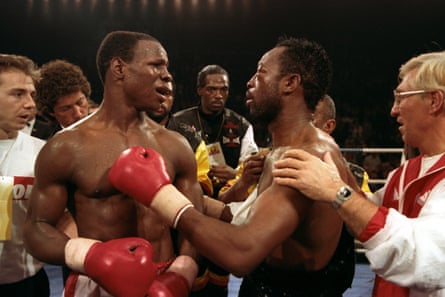

Thirty-five years ago this month, on 18 November 1990, my life changed course when I watched Chris Eubank and Nigel Benn fight each other in Birmingham with a ferocity which left me astonished and breathless. After that savage and surreal contest, I began working on a book about boxing, Dark Trade, which allowed me to become a full-time writer.

Benn and Eubank were so different that my already deep interest in boxing caught fire. I became consumed by the fight game for decades until, earlier this year, I finished writing The Last Bell, my fifth and final book about boxing. I still loved the most interesting fighters and their incredible life stories, but the controversies around the manufactured rivalry between Conor Benn and Chris Eubank Jr left me sick at heart.

That exhilarating first fight in 1990 ushered in a heady new era for British boxing. Soon, even people who cared nothing about boxing could not look away from the TV in roaring pubs when Benn, Eubank, Michael Watson, and later Lennox Lewis and Naseem Hamed, lit up the screen.

Briefly, those terrestrial TV viewers saw what I saw. They felt what I felt. Boxing looked less like a lonely freakshow then. It looked like a singular world filled with remarkable men who confronted their doubts and fears in the most elemental way. The fighters were extraordinary in crossing the bleakest terrain in pursuit of glory or redemption.

Now, in a different century, Benn and Eubank’s sons, Conor and Chris Jr, operate at a lower level, plying their trade in grim times as boxing is shunted even further to the margins. In these days of Saudi Arabian control and Dazn pay-per-views, of doping allegations and poor matchmaking, boxing seems bereft.

On Saturday night Benn and Eubank Jr meet in a rematch of their wild scrap in April, after two positive drug tests and rehydration clauses delayed and shadowed that contest for two and a half years. Hopefully the fourth fight between the families will mark the end of this overhyped feud and we can walk away in peace with our contrasting memories.

Eubank Jr was born on 18 September 1989, exactly 14 months before his father faced The Dark Destroyer. Nigel Benn was a prohibitive favourite because he was a knockout merchant while Eubank was dismissed as a dandy who proclaimed that “boxing is barbaric”. He also warned Benn that “this is the intellectual boxer against the shallow-minded puncher”.

Benn sneered: “I hate Eubank. I’ll give him a hiding.”

The atmosphere on fight night was electric and I was hooked from the moment Eubank walked to the ring. He was furious as Benn’s manager, Ambrose Mendy, had cut off his entrance music – Tina Turner’s tedious The Best.

Conroy Smith’s far more addictive Dangerous, a dancehall track as full of sunshine as Benn was crammed with darkness while running to the ring, accompanied booming chants of “Ni-gel … Ni-gel”. Eubank, who had vaulted the ropes, stood stock-still. It was riveting but nothing compared with the courage of the fighters.

A huge right hand rocked Benn in round four. His left eye was swollen and blinded. But, in that same round, Benn’s vicious uppercut badly cut his rival’s tongue. The next four rounds were trench warfare as Eubank swallowed so much blood.

He was down in the eighth but, near the end of the next round, Eubank unleashed a barrage of blows. Benn wilted against the ropes before the referee rescued him. It had been unremitting and unforgettable.

Eubank cried in the ring as he tried to explain his victory while proposing to Karron, the mother of Chris Jr, at home in Hove. “I beat him on determination. He hurt me bad, man. Karron, can we get married now? Marry me Karron … he hurt me with shots I never knew existed. But I hit him with everything. Karron, I done it. I need to go to hospital.”

Benn responded with decency and animosity. “He deserved it, man. He beat me fair and square … but I detest Chris Eubank more than anyone else.”

The pattern of my life for the next three decades was set. In Brighton a few months later Eubank and I sipped tea together in his favourite beachfront hotel. He was dressed in a darkly elegant Versace suit and impossibly shiny shoes. “What is in the nature of a man?” he pondered. “I may be said to have this Jekyll and Hyde personality. A gentleman outside the ring, a gladiator inside it.”

I asked Eubank to use five words to describe himself. He listed his adjectives alphabetically: “Approachable … brave … devious … generous … moody.”

Eubank pursed his lips. “Resourceful …”

“Chris, that’s six words,” I protested.

“I need six,” Eubank insisted, before telling me that “boxing is a terrible thing”.

Anyone who became so animated when talking about Mike Tyson could not be an advocate for the abolitionists. Yet the way Eubank lamented boxing’s worst features tapped into my own ambivalence.

What did it mean to call it “the noble art”, Eubank mused, when “boxing trades on the worst emotions. Look at how most boxers end up.”

Benn spoke bluntly when I met him: “Eubank has got to stop whining. I know more about boxing and life than him. I was a soldier in Belfast. The Troubles, man, made me shit my pants. But I got used to fear and now I like those fights which make me feel most alive.”

The gap-toothed slugger wore a black T-shirt sodden with sweat after sparring. “I don’t like Eubank outside the ring,” he said. “But we had a right old tear-up last time. I can’t wait for another to teach him a real lesson.”

It took almost three years before the rematch on 9 October 1993 at Old Trafford. Judgement Day was watched live by 42,000 fans and 16 million viewers on ITV. As happens so often in boxing it failed to match the hoopla – or the fire of their earlier bout – and Benn was unlucky it ended in a draw.

after newsletter promotion

That disappointment came between two tragedies. In September 1991 Eubank had staged a brutal comeback to defeat Michael Watson. Watson did not receive adequate emergency care at ringside and he slipped into a coma, ending up in a wheelchair. He still deals with the consequences today.

In February 1995, facing a terrifying opponent in Gerald McClellan, Benn displayed remarkable grit. It was one of the most violent fights ever seen in a British ring and it ended in the 10th when a distressed McClellan couldn’t continue. McClellan lost his sight, some of his hearing and suffered brain damage.

I interviewed Benn and Eubank many times over the years. They told me about divorce and bankruptcy, mental health concerns and Benn’s attempt to take his own life. And then, in November 2014, Eubank Sr introduced me to Chris Jr whom he described as “the most dangerous young man on the planet. There is a darkness in him I cannot measure.”

I shared an hour with Junior in the first of many interviews. When I pointed out that he seemed polite rather than dangerous he smiled: “In the ring I’m a different animal. I don’t think about the consequences for me or my opponent.”

A week later Eubank Jr lost his first bout – against Billy Joe Saunders. But he fought on and ended the career of Nick Blackwell, who was put into a coma. Eubank Jr spoke to me about that in 2016 as well as the recurring echo of Conor Benn – who had just become a professional. Conor was seven years younger and, tellingly, at least two weight classes lighter than him. The chances of them fighting seemed remote.

But there was too much money in it and so a contrived catchweight contest between Eubank Jr and Benn, hyped as Born Rivals, was engineered for 8 October 2022, one year short of the 30th anniversary of their fathers’ rematch.

I interviewed Benn Jr 10 days before the fight which was meant to be staged at 157lb. He was a welterweight and Eubank Jr had fought often at super-middleweight. It was a risky charade – especially for Eubank who had had to boil down in weight – and our interview did not start well. Benn was listless until he cracked and the tears poured out.

Nigel had already told me about the evangelical Christian school he had forced Conor to attend in Spain. The parent was dealing with his own demons and they warped his son’s upbringing. The family moved to Australia and Conor harboured resentment towards his father. As a teenager he was arrested by the Sydney police who took him home to his dad on a night which salvaged their relationship.

“How do you know all this?” Conor asked through the tears.

When he heard that his father had told me, Conor smiled and spoke compellingly for another hour. He also said: “My dad cares more about me than my boxing.”

I had a sudden and crazy hope that Benn’s showdown with Eubank Jr may elevate rather than diminish boxing. But, the day after our interview ran, news broke that Benn had tested positive for clomifene. I was incredulous that Benn and his promoter, Eddie Hearn, still hoped to proceed with the fight.

Forty-eight hours later, on the Thursday of fight week, the promotion was finally cancelled but my relationship with boxing would never be the same.

I spent the next two years writing many dispiriting articles about clomifene and boxing licences. Benn insisted he had copious evidence, which he never publicly revealed, to prove his innocence.

He remained suspended by the British Boxing of Control but obtained a licence to fight twice in Florida. Eventually, the National Anti-Doping Panel decided it was “not comfortably satisfied” an anti-doping violation had been proven by UK Anti-Doping and the board, clearing the way for Benn and Eubank Jr to bring their incessant goading of each other into the ring.

Seven months ago the fight happened. The buildup was dominated by the perilous rehydration clause to which Eubank Jr agreed limiting what weight he could put back on after the weigh-in and, when I interviewed him, he said: “I probably shouldn’t be doing it. But we are the daredevils of sport. This is not normal, punching each other as hard as we can in the head and body.”

There was a poignant undertow because Eubank Sr had called his son “a disgrace” and disowned him for his involvement in the fight. So I felt moved all over again when, just before Eubank Jr left his dressing room, the big screen showed footage of Senior arriving at the stadium. Father and son made an electrifying walk to the ring together as the arena rocked with delirium.

The fight was exciting – but low on skill. Eubank won 116-112 on all three scorecards but I was impressed by Benn because, an hour later, he came out to speak to us. “I know Chris has gone to hospital, so I wish him a speedy recovery,” he said. “I also want to thank Senior for turning up because this is a family affair.”

Eubank Jr’s dehydration was so acute that he spent two nights in hospital and lost £375,000 to Benn after missing the first weight cut. It is madness that they should be fighting again under the same hazardous stipulations but, of course, this is boxing. The Benn and the Eubank families remain locked together in their desperate last dance to the end.

2 months ago

48

2 months ago

48