Three years after the end of the Tigray war, Ethiopia is grappling with a violent armed insurgency devastating the north-west of the country. The Fano, an ethno-nationalist militia composed mainly of former soldiers from the Ethiopian regional special forces, now control large areas of the Amhara region.

Abuses committed by federal forces in an attempt to quell the insurgency are widespread: kidnappings, massacres, sexual violence, and attacks on humanitarian personnel. The situation is out of control, and more than 2 million people are in urgent need of humanitarian assistance in a region that is also hosting refugees from the war in Sudan.

-

Landscapes in the Lasta mountains, in Ethiopia’s Amhara region. This area spans a vast mountainous and hilly zone, bordering Tigray and Sudan. Its geography, typical of the Ethiopian highlands, offered a strategic position to the early kingdoms, making it the country’s main political, economic, and religious centre for centuries.

-

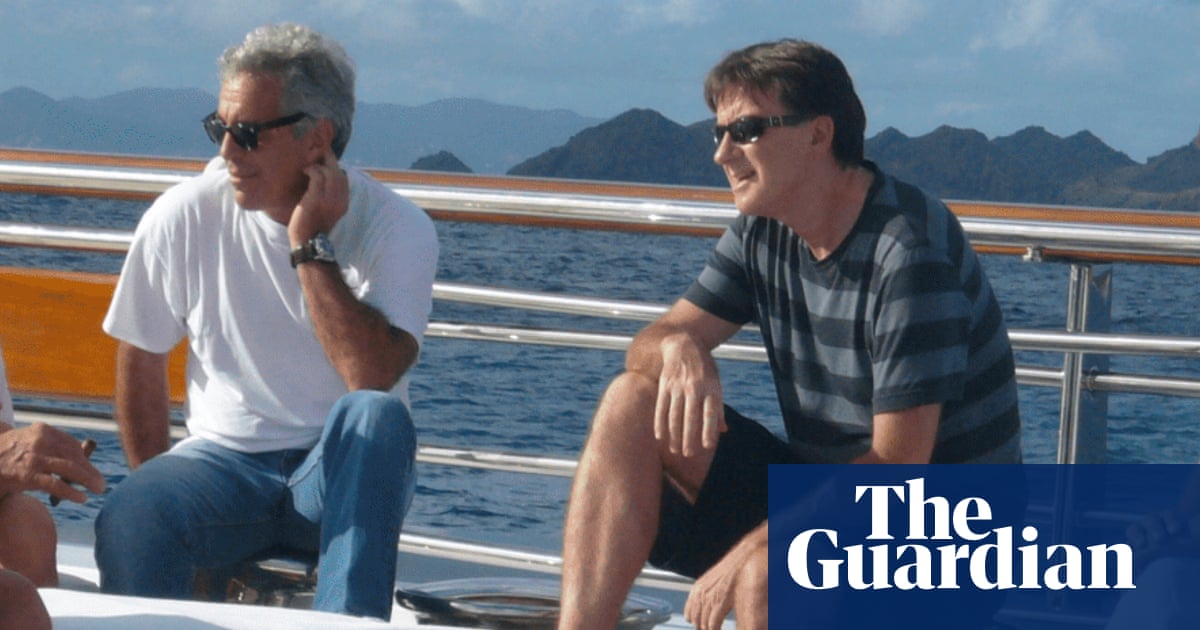

Two members of the Fano nationalist movement look out over the Amhara mountains, the birthplace of their movement. The term ‘Fano’ revives the name of a volunteer armed group that, in the 1930s, led a successful campaign against the fascist Italian occupation of Ethiopia.

Northern Ethiopia is witnessing a sharp escalation in tensions, and the Pretoria Agreement, which ended the Tigray war (2020–2022), has never seemed more fragile. Addis Ababa has accused the Tigray People’s Liberation Front of preparing a new war, possibly in coordination with Eritrea. The escalating war of words between the two countries over access to the Red Sea – which the Ethiopian prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, has described as existential – is fanning the flames of a large-scale conflict in the Horn of Africa. Yet, although the Tigray war, which claimed more than 600,000 lives, has officially ended, fighting has never truly ceased in the northern regions. In Amhara, bordering Tigray and Sudan, the insurrection is spreading.

-

A young Fano soldier crosses a field at the foot of the village of Ejafat, in North Wollo, Amhara.

Amhara, Ethiopia’s second most populous region with about 33 million people, has seen the rise of the armed Fano movement since 2023. This nationalist militia claims to represent and defend the Amhara ethnic group, which predominantly inhabits the mountainous territory. Once allies of the federal government, the Fano played a central role during the Tigray war, fighting on multiple fronts and administering territories west of Tigray long claimed by these local nationalists. The Pretoria Agreement has reshuffled the deck: former allies are now enemies, with Amhara militiamen feeling excluded from the peace deal. “A deep sense of betrayal has swept through the region and the Amhara people, who were already heavily affected by the war,” Tutenges says.

-

On their way to one of the fronts, Fano soldiers from North Wollo drive through numerous villages under their control. Fano militias claim to control more than 80% of the Amhara region – primarily the rural areas.

-

A mother and her two children pray on 11 May inside Yemrehanna Krestos church, an important place of worship of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, now under Fano control in the Amhara region. One by one, women, men, and children come forward to kiss the door of the holy site and pray for victory, the end of the fighting, and the return of peace in the Amhara region.

The situation worsened when the government announced the dismantling of regional special forces, largely consisting of Amhara fighters. This was perceived as a direct threat to their security in a country where ethnic tensions run deep. The Amhara, Ethiopia’s second-largest ethnic group, have been victims of massacres in recent years, particularly in areas where they are a minority. These atrocities, often carried out by insurgents from other ethnic groups – Tigrayans or Oromos – have rarely been punished by the government, fuelling hatred and trauma. Meanwhile, the Fano are also accused of multiple abuses and ethnic cleansing in Tigray, particularly in Wolkait and Raya, territories they annexed during the war.

-

Young Fano fighters from North Wollo prepare to go into battle on 12 May. The four main Fano command divisions, covering the entire region, from Gondar to Gojjam, extending into the recently conquered northern lands of Tigray, have recently announced the creation of a new joint political structure: the Amhara National Fano Force (ANFF). This aims to unite their forces around their ideology and demonstrate unity against the government, which seeks to divide them.

In response to the dismantling attempt, thousands of these fighters joined the Fano ranks, bringing military experience and weapons, creating an armed movement of nearly 20,000 combatants, which remains fragmented and without a clear hierarchy. The fighting has since intensified dramatically. The Fano have taken control of vast rural areas in Amhara, forcing federal forces to retreat into major regional cities, where insurgents occasionally launch lightning raids. Eritrea is suspected of training the militia.

-

Civilians queue for rations in Amhara, north Wollo.

Today, the region is divided into areas alternately controlled by federal forces and the Fano, who themselves are split into different factions. “Frontlines and areas of control shift constantly, and the checkpoints set up by each side make the region highly unpredictable and difficult to access,” says Tutenges, who visited northern Wollo, east Amhara, in May 2025. There, he spent several days with the Fano controlling part of the Lasta massif, near Mount Abuna Yosef, 4,260 metres high, overlooking the holy city of Lalibela. The journey spanned about 100km across Ethiopia’s highlands and villages under insurgent control, where the Addis Ababa government holds no authority.

Amhara has long been Ethiopia’s political, economic, and religious heartland, regarded as the country’s cradle. Along the route, many Orthodox Christian churches, nearly a millennium old and carved directly into the rock, attract crowds of militiamen and civilians. The Fano emphasise this heritage, portraying their community, descended from King Solomon, as the embodiment of “Ethiopianness” and aspiring to reclaim greater political influence. Their ambitions range from asserting full control over the Amhara region to toppling Ahmed’s federal government.

-

In the Lasta mountains, about 100 young Amharas train for combat in one of the Fano training camps in North Wollo, Amhara region. Many were students, farmers, or engineers before the intensifying fighting plunged large parts of the region into war.

-

Many women, like Ayehy, 20 (right), and Asefg, 19 (left), seen here in a camp in North Wollo, Amhara, have decided to join the Fano and are now training for combat.

In the mountains, hundreds of young people are also being trained in weaponry under Fano instructors. “Many are barely in their 20s and have joined the Fano driven by hatred of federal forces, who carry out abuses to suppress the insurrection. Others are here because they have no alternative, as the economy in this war-ravaged region is depleted,” says Tutenges, who spoke to the young recruits.

The Ethiopian federal army is regularly accused of massacres, arbitrary arrests, sexual violence, and targeted attacks on civilians in Amhara, often using drones. On 27 September, for example, a drone strike on a health centre in Sanqa, a few kilometres from Lalibela, killed four people, including a pregnant woman, and injured dozens more.

-

Civilians pay a heavy price in this war and often find themselves caught in the middle of the fighting. Gete Beyono, 23 (centre), pictured on 9 May in the town of Bilbala, under Fano control, was crossing her field in late 2023 when an Ethiopian army mortar shell exploded. Her five-year-old son, whom she was holding by the hand, was torn apart by the blast. ‘Only my daughter, who survived the attack, still gives me a reason to live,’ the young woman confides.

Throughout his reporting, many civilians recounted such abuses. One man lost his 83-year-old mother in Bilbala, killed when a federal drone struck her home; another woman’s five-year-old child was torn apart by a mortar shell fired from heights held by the government. These atrocities fuel local anger at the central government and increase the Fano’s legitimacy. While the Fano enjoy widespread community support since the start of the insurrection, growing insecurity and the collapse of the economy are gradually undermining this trust, as some Fano groups are increasingly accused of extorting civilians, in particular at checkpoints.

The war in Amhara has also created a dire humanitarian situation. From the Tigray war to the Fano uprising, more than 670,000 people have been displaced within the region, which also hosts refugees from the neighbouring Sudanese conflict.

-

Fano checkpoints line the main roads, such as here, just 6km from Lalibela, a government-held town, on 11 May, in the Amhara region. Approximately every 10km, a handful of young men with Kalashnikovs slung over their shoulders block and filter traffic, sometimes using a simple rope stretched across the road. Local populations move from one area of influence to another throughout the day.

Humanitarian aid struggles to reach most affected areas, hindered by federal forces and unpredictable checkpoints. Health centres are frequently targeted, and there have been documented cases of federal soldiers firing on ambulances or arbitrarily detaining medical staff treating patients suspected of being Fano. By 2024, 2.3 million people in Amhara were in urgent need of help.

2 months ago

54

2 months ago

54