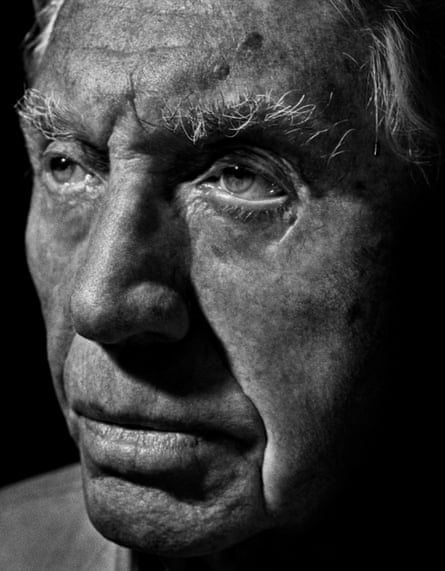

At 90, McCullin has spent seven decades recording conflict and tragedy – while escaping snipers, mortar fire and capture. He reflects on pain, pride and regret

War photographers are not meant to reach 90. “Fate has had my life in its hands,” says Don McCullin. Over his seven-decade career covering wars, famines and disasters McCullin has been captured, and escaped snipers, mortar fire and more. How does it feel to be a survivor? “Uncomfortable,” he says. No wonder he finds solace in the beautiful still lifes he creates in his shed, or in the images he composes in the countryside around his Somerset home.

McCullin is proud of escaping the extreme poverty he was born into, and the interesting and adventurous life he has lived, but he says the accolades – including a knighthood in 2017 – make him uneasy. “I feel as if I’ve been over-rewarded, and I definitely feel uncomfortable about that, because it’s been at the expense of other people’s lives.” But he has been the witness to atrocity, I point out, and that’s important. “Yes,” he says, uncertainly, “but, at the end of the day, it’s done absolutely no good at all. Look at Ukraine. Look at Gaza. I haven’t changed a solitary thing. I mean it. I feel as if I’ve been riding on other people’s pain over the last 60 years, and their pain hasn’t helped prevent this kind of tragedy. We’ve learned nothing.” It makes him despair.

The most harrowing photographs are McCullin’s best-known, but his career, which began 67 years ago, spans many genres, including beautiful landscapes, portraits and photographs of ancient ruins and antiquities. On a recent late autumn day, we sat at his table, surrounded by laden bookshelves, in a lovely room overlooking land on which he has planted many trees, and he talked me through his life in pictures.

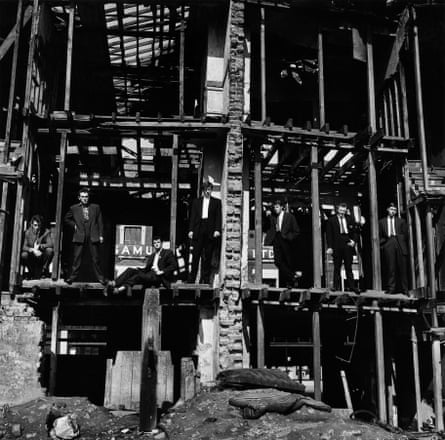

Guvnors, Finsbury Park gang, 1958

McCullin grew up in north London, in a damp two-room basement in a tenement building. His father suffered chronic asthma and died when McCullin was 14. He left school soon afterwards. National service with the RAF followed, and that was where he discovered photography. This photograph, of a gang of young men McCullin grew up with, was published in the Observer when he was 23 and had been working at a London animation studio. It started his career.

In Finsbury Park, people’s doors were always open. My mother was never home because she worked on the railway. We had gaslight, and there were lots of horses around, delivering coal or for the brewery. Sometimes, they’d let you sit on the back of one. I come from another culture.

During the war, I was evacuated three times, and each time I’d come back to a London that was more derelict. We would climb these bombed buildings. It was like climbing inside cathedrals, the carcasses of these buildings, and we’d sit at the top eating chips stuffed into a roll. In a way, I had a real childhood. Sometimes, we would get the train up to Cockfosters, run across the live rails into the countryside and capture grass snakes and birds’ eggs. Children don’t have a life like that today.

I used to get battered by bullies. I’d win the odd fight, but I would lose a lot of others. These boys in the photograph, all they talked about was violence, robbery, housebreaking. One of them was an armed robber who had been in prison.

I was surrounded by violence and bigotry and it was getting to me. These people hadn’t travelled like me. I’d been to Sudan, Egypt and Cyprus with the RAF, and started developing a mind of my own.

But my background of no education, bigotry and all that awfulness makes me feel like the impostor in the room. Despite all I have learned, I still feel uncomfortable.

Near Checkpoint Charlie, Berlin, 1961

By the early 1960s, McCullin was freelancing for the Observer and other newspapers and magazines. He and his first wife, Christine, were still living in Finsbury Park in a two-room flat – one room was bathroom, kitchen and his dark room combined.

I was sitting in a cafe with my wife in Paris on a belated honeymoon. I saw a man reading Le Figaro, which had a picture of an East German soldier with his Kalashnikov. I said to her: “When we go back, would you mind if I went to Berlin?” We’d only been married a few months. I asked the Observer if they wanted pictures, and they said: “We’re not sending you. It’s up to you if you go or not.” I went with a camera that I had used to photograph the Finsbury Park gang. It was a Rolleicord I had bought when I finished my national service. It was very difficult to compose [pictures with it] because it’s in a square format. I had pawned it once for five quid, and the one decent thing my mother did was she got that camera out. I saw other international photographers arriving, draped in all the latest cameras and I remember feeling shabby.

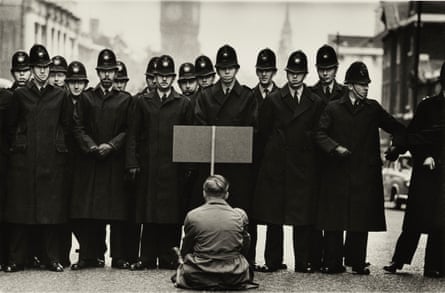

Protest picture during the Cuban missile crisis, Whitehall, 1962

This man ran away from Trafalgar Square and they immediately blocked his way to Whitehall. I did a lot of political demonstrations when I worked on the Observer in the early 60s, and I loved it. There used to be brawls some days, which I could get involved in, photographically. I find this photograph amusing. Despite everything, there is laughter in me. I’ve got a huge sense of humour.

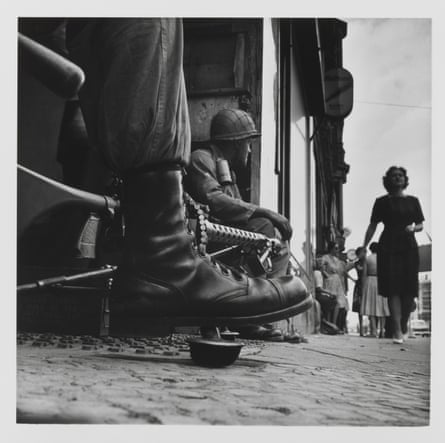

The Cyprus civil war, Limassol, 1964

During the first war he covered, McCullin found himself in the middle of a gun battle when Greeks surrounded the Turkish quarter of Limassol. Turkish civilians had hidden in communal buildings, such as cinemas, where this photograph of a Turkish gunman was taken.

I went into the Observer newspaper – I had a contract with them for two days a week for 15 guineas – and the editor said: “Would you consider going to cover the civil war in Cyprus?” I felt as if I was levitating. On my first day in Limassol, I took this picture, by the side of a cinema. It looks like a Hollywood still: the man is far too well dressed. In the evening, when the battle stopped, I had nowhere to stay, and the Turkish police said I could sleep in a cell block. That was my baptism in war.

On another day, I was walking towards a village, and a British solder said: “Dead body up there.” I walked, looking at the ground, afraid to raise my head and I found the first body. I went to a house, knocked on the door, but there was no answer. I gently opened it and the first thing that hit me was a warm smell of blood. There was blood all over the floor. There were two dead brothers, and their father was in the kitchen at the back, murdered by the Greeks. I was in the house, photographing, when suddenly the door opened and several people came in, including a woman, crying for her dead husband, who she’d only married a couple of weeks before. I thought, “They’re going to attack me”, but they didn’t. They were very generous towards me.

I felt I had chosen the right thing to do, because I found what I was photographing so outrageous that I couldn’t wait to get back to England and see my pictures published, to show the world how wrong it was. When you’re young and ambitious, you haven’t really worked it all out. You’re drawn to this tragedy, but it doesn’t belong to you – you’re imposing yourself upon the situation. You’re not welcome or invited and you’re stealing in a way. You’re stealing other people’s emotional tragedies. You’re stealing images of people, dead, who haven’t given you consent. I was aware it wasn’t totally right, and I believe it to this day. That’s why I come back here and do the English landscape. I feel as if I have to release myself from my guilt, which I still carry.

Suspected Lumumbist freedom fighters being tortured, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1964

The German magazine Quick sent McCullin to cover events in DRC, where followers of the assassinated prime minister Patrice Lumumba had captured the eastern part of the country. Arriving in what was then Léopoldville (now Kinshasa), he discovered members of the media were being banned from leaving. Meeting a mercenary in his hotel bar, one of many mercenaries employed by the government to fight the rebels, McCullin persuaded him to lend him a uniform and get him on a military plane to the rebel stronghold Stanleyville (now Kisangani).

I got on the runway in the early morning and before I got on the plane, they were running off people’s names. I thought: “Oh my God, they’re going to discover I’m not a mercenary.” The guy said: “What’s your name?” I said: “McCullin.” He said: “Get on the plane”, and I flew 1,000km to where [military leader] Joseph-Désiré Mobutu said no press were allowed to go. When I got to the other end, I found [the loyalist gendarmerie] were torturing boys as young as 17 and maybe younger. They were shooting them in the back of the head and kicking them in the river. These boys were Lumumbist. They were beating them; one of the boys had been stabbed in the face with a knife.

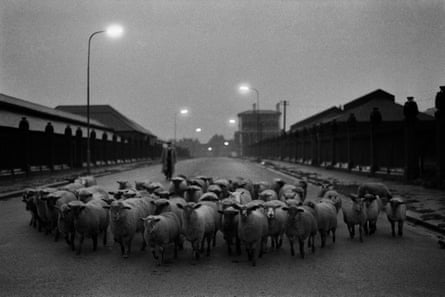

Sheep going to slaughter, London, 1965

That was on the Caledonian Road, where there used to be big abattoirs on either side. I was working on a magazine story with the writer Eric Newby, who has long died. So many people I’ve worked with have died, I feel as if I’m one of the few left who knew this world I worked in.

Grenade thrower, Hue, Vietnam, 1968

McCullin went to cover the Vietnam war for the first time in 1965, and returned several times.

I joined these US marines, and they said it was going to be a 24-hour operation in the ancient city of Hue. Twelve days later, we were still there – they got a terrible hiding. They lost about 40 men; a sniper was picking them off every day. You can see the devastation in this photograph. I slept in a hut, on the floor, under a table, using my helmet as a pillow. I loved being tested to the limit. In the mornings, I always left the hut one way, and then one day I decided to turn another way. Behind the hut, I found a dead North Vietnamese soldier who had been lying almost head-to-head with me. He was about 18, his eyes were open and full of rainwater.

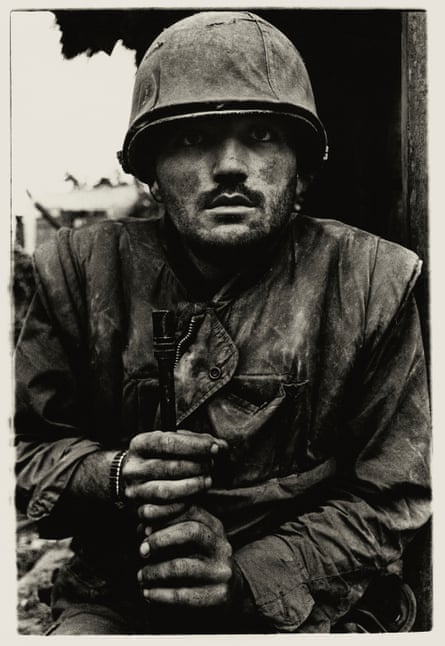

Shell-shocked US marine, Hue, Vietnam, 1968

I am slightly fed up with my more known pictures, because they’re classically, iconically composed. So what are they saying? They could almost be negative because they’re too perfectly designed by me, and people would say: “It’s almost artistic.” I’m afraid of falling off that very fine line.

I never harmed any of the people in my pictures. I didn’t kill them. I didn’t torture them, the way this man has been tortured by his own breakdown.

Every night, I remember the battle that that man was in. I didn’t get his damaged brain, but my brain has never been free of certain images. I have bad dreams and this pause every night before I sleep, but I’ve never suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder.

I was moving fast. I would go straight back to another war. There’s an adrenaline rush. It’s all very selfish and stupid, but you’re not telling the truth if you say you didn’t find some sides of it exciting. The excitement of incoming shells. But then you think, “That shell just blew some guy’s leg off,” or killed another four or five guys. I’ve been swimming in a whirlpool of huge misadventure, and it’s been a cesspit, really, my life. There’s no other way of describing it.

I’ve risked my life a few times. I was in a gun battle once in Cyprus, and I saw an old lady who couldn’t walk. I thought, if someone doesn’t do something, that old girl is going to die in the next five minutes. I gave my friend my cameras and ran and picked her up and then ran back with her. I thought: “I can’t keep taking all the time. You’ve got to do something, give something back.” In Vietnam, I carried a soldier away from battle on my shoulders. He had been hit by a bullet and was in such pain. I thought: “I’ve been stealing all these years. I’ve got to hand some of that back.” But you risk your life doing it.

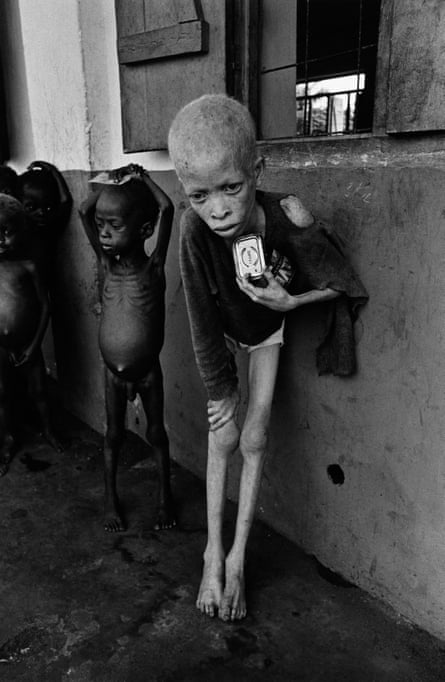

Starving boy, Biafra, 1968

The day after his third child was born, McCullin left to cover the war that had broken out since Biafra had broken away from Nigeria in 1967. After witnessing battles, executions and more horrors, then coming down with malaria, McCullin was about to see the sights that would probably haunt him most, at a hospital for war-orphaned children, where hundreds were starving.

This is possibly the most atrocious picture I’ve ever taken in my life. There were 600 children dying in this camp. They were dropping down and dying in front of me. When they see white people, they think you’re an aid worker coming to bring them food. So you can understand my guilt, can’t you? It was not kind of me to be there, really.

That boy is holding a tin of corned beef, which he had completely licked dry to get every gram. I gave him a barley sugar sweet, which I had in my pocket, and he went away, licking it. I went off and spoke to a Médecins Sans Frontières doctor, and I felt someone take hold of my hand. It was the boy. It made me feel so bloody guilty.

I haven’t printed that picture for nearly 30 years now. I don’t want to see it coming up in the dark room. I even feel guilty that these pictures – I have about 70,000 negatives – are in the house.

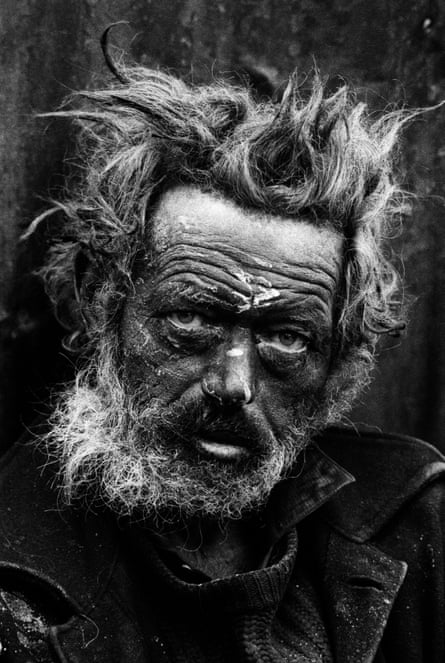

Homeless Irish man, London, 1969

There are social wars on your doorstep. People used to write me letters, saying, “I want to be a war photographer.” I’d say: “Help yourself – it’s in your cities.” This man slept by a fire in Spitalfields market, very close to the City of London, which generates billions and billions of pounds for the people who own it. You couldn’t have more of a contrast. One side is everything, and the other side is nothing.

I call this picture Neptune, because he looks like the sea god. I thought he was one of the most handsome men I had ever seen.

Catholic youth escaping CS gas fired by British soldiers, Londonderry, 1971

During the late 1960s, McCullin was barely home. He covered war in Chad and trekked to rebel camps in Eritrea. Even though he was injured while photographing the civil war in Cambodia – watching the man who had taken the full force of the mortar blast die in front of him on the way to hospital – he was back several months later. He photographed tribes in the Amazon rainforest, whose lands were being taken, and the refugee crisis caused by war in Pakistan. On that particular trip, McCullin decided he was more interested in showing the impact of violence on civilians – something he was able to do in Northern Ireland.

I spent six weeks in Northern Ireland. This is the gassing, in the Bogside area, of Catholic youths. I got gassed really badly that day, and hit in the back with a rubber bullet. I was led away, totally blind, into a house where there was a hell of a lot of swearing and shouting. “Get him a damp cloth!” It was chaotic.

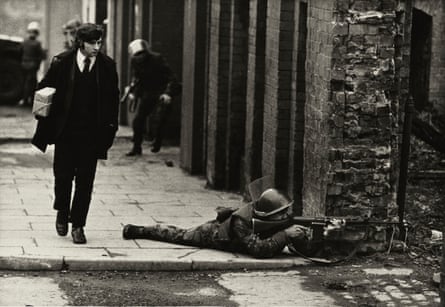

Man and British soldier, Londonderry, 1971

That man is coming home from work and that soldier’s behaving like a soldier. It does seem to be the extreme contrast of a normal man coming back from a normal day, having to share the street.

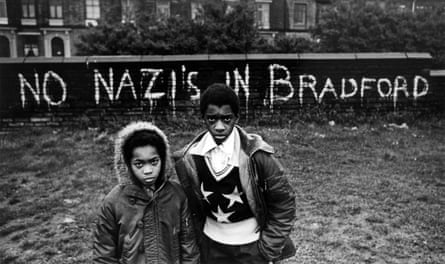

Local boys in Bradford, 1972

Back from whatever war zone he had been sent to, McCullin would set himself photographic projects. He often went to the north of England, drawn to documenting people’s hard lives in run-down industrial landscapes.

I used to walk the streets, and the people in the north are very friendly, a lot more trusting than the people in the south. I went to Bradford, and I saw that amazing slogan on the wall, against the racism of that period. I’m proud of my work in the north of England. I was evacuated as a child to Lancashire, to a chicken farm for 18 weeks, and I had a really horrible time. That is one reason why I don’t treat other people badly.

If I had been to university, I think I would have been a more sensitive person, even more than I already am, and I would not have been able to sleep among dead bodies and rat-infested trenches and things like that. Also, I knew how to conduct myself. You smell poverty when you go into a house and it smells just like the house I grew up in as a boy.

A winter’s victim, Hertfordshire, undated

In 1972, McCullin and other journalists were captured in Uganda, and he was sure he would die in the notorious Makindye prison, listening to fellow prisoners being taken away to be beaten or executed, and watching trucks taking bodies away. After four days, he was released and deported, arriving home to his family – now living in a farmhouse in Hertfordshire.

I found this sparrow outside my house one day, at dusk. I’ve got good eyes, I spot stuff on the floor, everywhere. I kind of X-ray things.

Young Christians celebrating the death of a Palestinian girl, Beirut, 1976

Having been to Lebanon several times in the 1960s, when Beirut was a decadent playground for the rich, McCullin returned to cover the civil war in the mid-1970s. Arriving in Beirut, he decided attaching himself to the Christian Phalange militia would give him the best access. Over the next few days, he photographed the massacres in a district in east Beirut populated largely by Palestinians – which would put McCullin’s name on a death warrant.

One morning I was told: “We’re going to Karantina and we’re going to clear out the rats.” They meant Palestinians. I slept in the morgue that night and then in the early morning, they attacked the area.

I was told to leave the area by the Christians. They said: “If we see you taking any more photographs, we’re going to kill you.” I’d been watching them kill Palestinians in groups, pouring magazines into men’s heads and exploding them. I was leaving when I heard this strange music and I saw this. This is a dead Palestinian girl lying in the rain, and this boy had a mandolin, which he found in one of the houses. He couldn’t play it, but he was giving the impression that he was serenading the death of this girl. I was looking around, thinking: “I’ve got to get this picture.” I took it very quickly.

Dew pond, Somerset, 1988

By the mid-1980s, McCullin’s type of work had fallen out of favour at the Sunday Times, newly acquired by Rupert Murdoch, and he left. Personally, it had also been a difficult time – he had been injured in El Salvador, after falling off a roof in a gun battle, and he left his first wife for the woman who would become his second, something he says he still feels guilty about (he has been married to his third wife, Catherine, a writer and podcaster, for more than 20 years). Money was short, and he turned to advertising photography, even though it didn’t fulfil him. Moving to Somerset, he found peace in photographing the landscape around his new home.

Dew ponds are very rare things. They are almost mythological. They’re completely round, and this one was at the foot of a hill fort. We’re surrounded here in Somerset by history and myth. I use that. This was in the early morning, but I usually work in the evening, when the sun is going down.

I can stand in these fields for two or three hours and not get a picture. That doesn’t mean to say I’m disappointed, I’ve had the privilege of standing there. There’s nothing greater.

Photojournalism has taken a nosedive, and it’s because newspaper proprietors want beautiful women, rich people, celebrities. They do not want my kind of pictures in their paper, spoiling their day. They don’t want that tragedy.

Tulips with a mind of their own, undated

I study things. You watch tulips, they start in a very kind of pristine way, and in the end they start dancing in different directions. This is free of charge, a total joy ride. They can’t say to me: “Don’t photograph us in our deaths.”

The road to the Somme, France, 1999

I was commissioned by Royal Mail to create a commemorative stamp of the first world war. I was in a French bistro one day having lunch and it had been raining. I was going back when I suddenly saw this silvery wet road, and I swung my car around. I thought that that horizon would be the huge graveyard of thousands of men who didn’t want to die, men who hadn’t had a life at the age of 18 and younger.

Refugee camp, Chad, 2007

I was sent by Oxfam to photograph refugee camps in Chad [people fleeing violence in Darfur].

In places I’ve worked, I have seen television crews coming in, treading on kids and pushing people around, thinking they are more important. I’ve always been tough with those people – growing up in Finsbury Park meant I wasn’t a pushover. But when it comes to my work, I am very sensitive, very polite. I’m a human being. I would never have got pictures of people who are injured and angry and hurt without that, and I’ve managed to allow them to give me that moment of trust. If I wasn’t thinking like that, my pictures wouldn’t have a sensitive way of trying to speak to you.

The exhibition Don McCullin: A Desecrated Serenity is at Hauser & Wirth, New York, until 8 November. McCullin’s new book of still lifes and landscapes, The Stillness of Life, is published by Gost Books, price £80.

2 months ago

42

2 months ago

42