Jude Black was delighted when her son, Joe, moved into Holmes Road Studios in Camden, north London. This wasn’t any old homelessness hostel. It had just won an award from the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and it looked gorgeous.

The 59 refurbished studio flats had en suite bathrooms and were designed around a courtyard garden. Joe was allocated No 21. Each studio was distinguished by a colourful front door – blue, brown, orange, green, red, turquoise. The rustic-looking brickwork gleamed in the sun and a stylish porthole window lit up the mezzanine bed space.

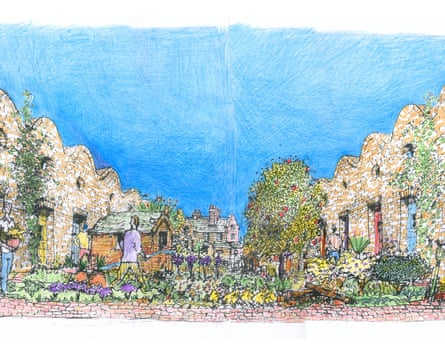

Peter Barber Architects, which designed Holmes Road, referred to the studio flats as cottages and envisaged the inhabitants transforming the place into a horticultural paradise. “We imagine a group of residents working with a gardener to create and maintain an intensely planted and beautiful garden,” stated the project’s manifesto. “There would be an apple tree or two, potatoes, green veg, soft fruit, herbs, a greenhouse, a potting shed and a sunny spot to sit and rest. We think there ought to be a little room/shed in the garden for private chats (1:1) and counselling.”

Holmes Road, in the constituency of the prime minister, Keir Starmer, was created for single homeless people with support needs. A citation for the RIBA award stated that the hostel provided counselling, education and training spaces. After a maximum of two years in this temporary accommodation, residents would hopefully progress to independent living. Holmes Road was called a sanctuary.

Jude felt Joe would be shielded from danger here. Holmes Road rigorously asserted its zero‑tolerance drug policy. If lucky enough to be offered a place, residents had to promise not to take drugs on the premises – and, ideally, not at all. This was vital for Joe, because he was vulnerable, with a dual diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia and a substance use disorder. In his previous flat, he had been cuckooed – drug dealers moved in, took over and used the place as an office. It was terrifying and traumatising for Joe. Now more than ever, he needed the promised sanctuary.

Two years after moving into Holmes Road, Joe was found dead, slumped over his kitchen table, surrounded by drug paraphernalia. He was 39.

Joseph Forbes Black was a gifted musician and composer. His specialism was bass guitar; he passed grade 8 with the highest mark in the country. He was adored by his family – Jude, a special needs teacher; his father, Andy Forbes, who has been the principal of a number of further education colleges; and his two sisters and baby niece. He was quiet, sensitive, loving, smart and troubled.

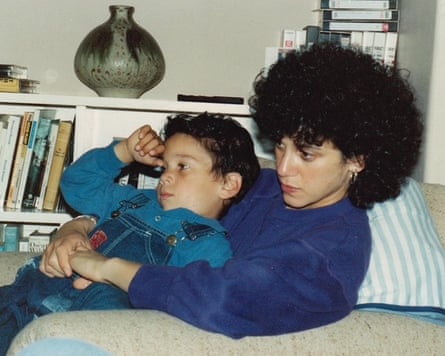

It’s October 2023, two months after Joe died. Jude and I meet in a cafe in north London, close to where she lives. Her black hair is swept into a ponytail. She looks gaunt and distraught. Jude shows me pictures of Joe. “This is him as a little boy. And that’s him holding his niece – his elder sister’s baby. He was so looking forward to watching her grow up.” It sets her off. “So many beautiful photos,” she says, through tears.

She moves on to photos of his flat after he was found. It’s filthy. Jude believed he would get help keeping his place tidy. After all, this was supported accommodation with the aim of helping people back to independent living. She tells me the hob wasn’t working, so he couldn’t cook. “He was living in squalor. He wasn’t edging in the direction of living independently – he was deteriorating.”

As a young boy, Joe was outgoing, loving and hugely popular. He was obsessed with music and it was obvious from an early age that he was gifted. “He used to say: ‘Music keeps me alive, Mum,’” says Jude. At seven, he was playing baby bass at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester. He went on to write, produce and record music under the name Nexus 23 and graduated with a degree in creative music production and business before starting a master’s in music at the Institute of Contemporary Music Performance in London.

Jude and Andy split up in 1990 when Joe was seven, but remained friends, committed to doing the best for their two children. After their separation, Jude moved with the kids to Oxford, where they lived for 10 years, then to Brighton. She had another daughter, Georgia.

In his statement to the coroner, Andy said he became aware of Joe’s illness when his son was in his late teens. “I drove to Brighton to bring Joe to stay with me in Manchester. His flat and clothes were filthy; he was talking nonsense and showing clear signs of psychosis.” Andy was familiar with the symptoms. “There is a strong history of psychotic mental illness in the Forbes family,” he told the coroner.

Joe was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. As this became more debilitating, his drug and alcohol use became more problematic. Jude says he was self-medicating. The outgoing boy became an introverted, self-conscious man. The older he was, the younger he behaved. Joe would often tell Jude how much he struggled with life as an adult. He sent her a message saying: “I wish I was a baby so I could live my life over again.”

His health deteriorated in his 20s and he became more paranoid. He told Jude and Andy that he didn’t believe they were his true parents and that he was descended from Egyptian royalty. He struggled with frightening delusions and hallucinations, which only made him feel more isolated. Joe sent Jude messages saying: “Mum, I have a terrible mental illness,” and: “Mum, I am monumentally depressed.” He believed he was the target of racism, that everyone hated him and that he had no friends.

Joe struggled with identity. He loved his mixed heritage, but it also confused him. He wasn’t sure who he was or where he belonged. Jude is white and Jewish (she lost relatives in the Holocaust); Andy is Anglo-Irish and half Jamaican. Joe was equally confused by class. His family had done well for themselves through education (Andy’s father had been one of Britain’s first black GPs) and Joe couldn’t place himself. “He’d say to me: ‘Am I a posh boy, Mum?’ And then he’d say: ‘Am I a Gypsy?’ because people told him he looked like a Gypsy.”

Jude laughs when she talks about his fixation with their poshness. “My grandfather worked in a coat factory in Manchester. His parents moved to Manchester from the pogroms and they had a horse and cart. We weren’t posh!”

Another thing Joe really got wrong was that he wasn’t liked. People adored him, Jude says. Even at his most deluded, “he had such empathy for people and wanted to help them if they were struggling”.

In 2011, he went missing for 18 months. Even now, Jude finds it traumatic to discuss. “I would look at people sleeping in doorways and on the streets and wonder if they might be Joe. Every day, I thought he might be dead.” After he was found, Joe was sectioned for almost four months.

Over the next few years, he lived in a series of bedsits and flats in Brent, north-west London. He often neglected himself physically and struggled to look after his home. When he left hospital, he was discharged to the Brent community mental health team and allocated a care coordinator to make sure he attended his medical appointments and coped with life as well as possible. Jude speaks positively of the mental health team that looked after Joe in these years. When she raised concerns about him, his care coordinators told her it was helpful to have the family involved, because it meant the professionals could do their job more effectively. She would be invited to review appointments with Joe’s psychiatrist and care coordinator, where they would discuss his care plan. “Joe was comforted that we were all working together to monitor and support him,” she says.

In June 2020, Joe moved to a bedsit in Camden and was transferred to Camden community mental health team. Jude says they made it clear they didn’t want her input. She felt they regarded her as an interfering busybody. When she discovered Joe had not been given a care coordinator, she contacted north Camden rehabilitation and recovery team to express her concern, because she knew how dependent he had been on previous care coordinators. Joe was in acute distress, telling Jude he “would be better off dead”. Jude says the manager insisted Joe’s main issue was substance misuse, not mental illness, whereas at Brent it was accepted that he took drugs to self-medicate and a dual diagnosis qualified him for a care coordinator.

It was 2021 when Joe was cuckooed. Jude remembers how petrified he was when he called her. “He was very agitated and sounded very frightened. He said: ‘I’m lucky to be alive, Mum.’” He told her the dealers had put a gun to his head and ordered him to empty his bank account. He didn’t know how long they had been occupying the flat, but he said he had managed to escape. Joe told her he had used heroin and crack while being cuckooed, instead of ketamine and cannabis.

He withdrew from his master’s in north-west London, because the police told him it wasn’t safe to return to the area, and presented as homeless to Camden council. On 19 July 2021, a few weeks later, he was given an emergency placement at Holmes Road. When Jude looked it up, she thought it sounded perfect. But Joe was not convinced. He told her someone had offered to sell him crack there on the first day. She thought that might be his illness talking, or that he was trying to alarm her so she would agree to him living elsewhere.

She felt trapped. He was not capable of looking after himself in independent accommodation and she was not equipped to look after him at home. Holmes Road offered supported living. Surely he would be safest there? On 23 July 2021, Joe messaged her to say: “This place is full of crack addicts”; “I despise this place”; “It is like a prison.” Three days later, he left the hostel with all his belongings and went to stay in a friend’s flat. He told Jude he had left because “it is hell on earth for me”.

Jude was terrified he would lose his placement and go missing again. She told him to go back, otherwise he would not be rehoused. “I didn’t want him ending up on the streets. He was so vulnerable,” Jude says.

She is able to document Joe’s last years so comprehensively because she kept virtually every text, email and WhatsApp sent from and to Joe and those responsible for his care.

She was still convinced Holmes Road had to be better than the dilapidated rented accommodation in which he had been living; here, he would have one-to-one support with specialist staff. If things went well, Jude believed, he would be helped back to independent living. Another advantage was that the hostel was opposite Kentish Town police station. Holmes Road management said any drug dealing on the premises was immediately reported to the police.

In September 2021, Joe texted Jude to tell her he had been offered a full-time place at Holmes Road. She told him how pleased she was and asked what his room was like. “Shit,” Joe replied. “The manager admitted to me the place is full of drug addicts. How am I supposed to change in a hostel full of drug addicts?” Joe expressed his worries that he could “end up addicted to hard drugs again”. “Can’t you see this hostel is going to murder me?” he said. Jude was alarmed. She rang the hostel to ask if it was true about the drugs. She says staff just told her: “Joe has to stay strong and say no to anyone who offers him drugs.”

Joe was panicking. “He said: ‘You have made a massive mistake if you want me to keep away from drugs. Aren’t you worried about me being in this hostel?’ I asked: ‘Are you?’ He said: ‘Yes. This terrible hostel will kill me. The place is full of crack and heroin dealers and I want to stay clean from that.’

“These messages haunt me,” says Jude, her eyes red with tears. Again, she told herself Joe was exaggerating. She says she asked staff so many times about the level of heroin and crack use, but nobody acknowledged that it was a problem, so she put it down to Joe’s paranoia. After all, Holmes Road was so proud of its zero-tolerance drug policy.

On one occasion, Joe was bullied over money he owed a fellow resident. He said he feared for his life. The hostel took action on this occasion and the resident was expelled.

Every week, Jude would meet Joe outside the hostel (she wasn’t allowed beyond the reception) to buy him food, chat and check up on him. Joe was losing weight. He had a deep split on his bottom lip, which suggested crack use, he looked exhausted and he couldn’t manage his finances. He was always running out of money and was in debt to the hostel for his £16 weekly service charge. She thought it must be because he was spending all his money on drugs, but again the hostel staff expressed no concern.

When she said she was worried about Joe, she was told no information could be shared because of confidentiality. When she asked how he was doing, she was always told: “OK.” Nothing more. She was not invited to any meetings about his welfare or mental health, as she had been when Joe was in the care of Brent. She was never told about how he was progressing on the pathway towards independent living. It later emerged he hadn’t been put on a pathway. Holmes Road offers only short-term accommodation, for a maximum of two years, but there was no discussion about where Joe would go next, or when, even though the two years had passed.

On the evening of 3 August 2023, Joe messaged Jude: “Mum, I have literally no friends. Everyone I know is a snake in the grass. I cannot trust anyone.”

He claimed people were laughing behind his back, insulting him to his face and ganging up on him. Whether it was true or he was having a paranoid-schizophrenic episode, he was clearly not in a good way mentally. “And you wonder why I drink and take drugs,” he messaged Jude. “I have no friends. I have no job. I practically have no family. I have no home. What have I ever done to deserve this?”

Again, he said he doubted whether Jude and Andy were his real parents. He sounded desperate. “Plz talk to me mum. I’m feeling very unhappy and vulnerable and lonely … I have been hiding the truth from you for a while now … My life is getting progressively worse and worse.” It took Jude a few minutes to reply, which only increased his paranoia.

He sent another message: “See you don’t even care – you won’t even talk to me now. Are you my real mum? Be honest.”

But his mood was changeable. Five days later, on 8 August 2023, Joe messaged to say he had cheered up because Andy had helped him buy a new bike (he was working as a part-time delivery cyclist). Jude asked if he was still taking drugs. “It’s not my fault I suffer from very poor mental health,” he said. “Can’t you see I’m monumentally depressed?” He texted at about 11pm and said he was taking a night-time walk in Highgate.

Jude told him to take care. At 11.57pm, he texted: “Are you going to make your amazing cheesy pasta bake for me this coming weekend?” Jude said she was working that weekend and he should ask Andy to make it for him, because he was seeing him. “Ok no worries mum,” he texted at 12.07am. At 12.32am, Jude texted him: “How are things at Holmes Road? Is your new bike safely in your flat?” He did not respond to the message.

Later that day, the police knocked on Jude’s door to tell her Joe was dead.

Jude was determined to find out how Joe had died and what could have been done to prevent it. But when she asked staff at Holmes Road for information, no answers were forthcoming. There had to be an inquest and they were in no position to tell her what had happened. But she sensed that even if they could have helped her, they didn’t want to. She had always been the nuisance mother and she felt they still saw her like that, even in her grief.

She began investigating Joe’s death herself. She contacted all the agencies who were supposed to have been working with him. Some were helpful; some wouldn’t talk to her. The day after Joe died, she rang North Camden’s rehabilitation and recovery service to find out when Joe last presented at the depot for his monthly antipsychotic injection and what state he has been in.

Jude was told the service had received an alert about synthetic opioids being mixed in with other drugs three weeks before Joe died – there had been overdoses in Camden and this may have been why Joe fatally overdosed. After the call, Jude was emailed a National Patient Safety Alert dated 26 July and titled “Potent synthetic opioids implicated in heroin overdoses and deaths”. This was the first Jude had heard of the alert. At the very least, she says, if she had been told, she could have warned Joe of the dangers. A second email revealed that Joe had missed the last three reviews with his psychiatrist. The last time he had been seen was in November 2021, 21 months before he died.

Three weeks before Joe died, and a week before the emergency warning about dangerous synthetic drugs was issued, Holmes Road residents were sent a letter reminding them of the zero-tolerance drug policy.

Yet on 20 October 2023, two months after Joe’s death, the service manager for adult safeguarding and care management at Camden wrote to Jude, saying: “It is noted that people may continue to use both legal and illicit substances during their stay. In light of this, staff extend advice and support, striving to mitigate potential risks and helping those who wish to cut down or quit entirely. Staff are also conscious that for some, drug use may be a means of coping, often due to past traumas or ongoing personal struggles. It’s crucial to mention that any illegal activities identified within the hostel are immediately reported to the police and could result in eviction.”

There was a blatant contradiction. How could there be a zero-tolerance drug policy when they were saying that illicit substances could continue to be used by residents during their stay, with staff supporting those who wished to quit? In one sentence, it said they understood that residents would continue to take drugs as a coping mechanism; in the next, it said they would immediately be reported to the police. None of it added up.

Jude, Andy and Joe’s younger sister, Georgia, replied to the letter. “Not only did [the hostel’s] hopeless lack of support give Joseph permission to carry on using illegal drugs but it actually made him rely more and more on them,” they said. “We would also like to mention that Joseph had visibly lost weight over the two years that he was living at Holmes Road. He was also known to be constantly leaving and returning to the hostel, during the day and late at night. Why did this not cause any concern and why was this not addressed by the day and night time staff? We are heartbroken that Joseph was allowed to deteriorate and die in their care.”

When Jude and Andy went to collect Joe’s belongings, they were shocked by the attitude of the staff. They were greeted by the new manager, who had only been in place a few months. “She said: ‘I’m sorry, but he’s with God now.’ It was horrific,” Jude says. “I said: ‘Well, I’m not a religious person, so he’s not with God. He’s dead and he died at your hostel.’”

She met up with residents who had known Joe during his stay at Holmes Road. They were devastated by what had happened to him.

Mark, who lived at Holmes Road, says it was apparent to everybody that Joe was struggling. “He didn’t shower, didn’t wash. His room looked like a bomb had gone off – stuff all over the place. A keyworker who had any care for their client would say: ‘You can’t live like this, mate,’ and check up on him regularly, otherwise you’re letting people rot in their room. They were supposed to provide a breakfast club, coffee morning, art class. But there was none of that.”

What was Joe like? “He had a drug problem, but he was a nice person. He didn’t have a bad bone in his body. I believe he died because he was neglected by Camden council and staff here – left to do what he wanted. Class A drugs are rife here. I find it weird that staff turn a blind eye to it. They just let it happen. I don’t understand it. They’d have a go at you for playing music too loud, but let people smoke crack. I’ve never been in a hostel run like this. Holmes Road was like a legalised crack den and it’s across the road from the police station! It’s horrible. Absolutely horrible.”

Mark was evicted from the hostel. He believes it was for talking to Jude. “One day, the manager said to me: ‘Why are you going in and out of everyone’s room?’ I said: ‘I talk to people.’ They said: ‘We think you’re extorting vulnerable people.’ I was like: what? Next thing I know, they’re sending me to another hostel.”

Joe’s family called for an article 2 inquest because they believed the failings of Holmes Road and various agencies tasked with supporting him meant his right to life, protected by article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights, had been violated. Article 2 inquests are broader in their scope, tend to last longer and often have a jury. The assistant coroner for inner north London, Ian Potter, decided Joe’s death did not merit an article 2 inquest.

The four-day inquest began at Camden coroner’s court on 9 December 2024, 16 months after Joe’s death. At times, it felt as if the family were on trial. The counsel for Camden, Nick Stanage, insisted that Jude’s statement be hugely redacted. Potter agreed with most of the cuts, leaving less than 40% of her statement on record, which caused huge concern to the family’s legal team, who argued unsuccessfully that the inquest should be adjourned because of “procedural unfairness”.

Stanage said he thought the inquest could be done and dusted in one day and argued successfully that a witness from the hostel should not be allowed to give evidence because he had a criminal record and was therefore not of good character. Every time Stanage spoke, he seemed to reduce Jude and Georgia to tears. (At the end of the inquest, he told Jude that, if he had come across as confrontational, he regretted it. “I apologise to you if at any stage of this year or this week you have formed the impression of any personal hostility from me to you or any member of your family.”)

As witnesses spoke, the extent to which agencies had failed to act collectively, or at all, to support Joe emerged. Joe’s psychiatrist insisted it was not significant that Joe hadn’t seen her for almost two years because he saw an experienced nurse every four weeks for his antipsychotic injection. She said that when he did turn up to an appointment on 7 June 2023, only two months before he died, he couldn’t be seen because he had arrived half an hour late and she had to leave. She said he did not need a care coordinator because he had keyworkers at the hostel.

When the psychiatrist talked about her list of 300 patients and working with only one junior doctor, it was hard not to feel for her. Perhaps Joe would not have been so badly let down if services were better resourced. On the witness stand, she addressed Jude: “Before I leave, I want to say to you, Jude, my sincere condolences. And I valued the time we had on the phone and that I was able to listen to you.” It came across as sincere and heartfelt.

The next day, she took to the witness stand again to say she had got her dates wrong and couldn’t remember the day Joe had turned up late for his appointment. Her argument that a keyworker would suffice for Joe was contradicted by the hostel’s manager who said that keyworkers had no mental health training. “Two separate roles,” said the manager. “The keyworker role supports with housing-related roles. The care coordinator, the NHS worker, deals with the mental health needs. We are not trained mental health workers.”

The manager said that although they often met with mental health professionals to support residents, “in the case of Joe, there was nothing like that, because there was no issue with his mental health that we saw”. Yet, according to fellow residents, he was clearly struggling with paranoid schizophrenia. As for drugs, the manager stated categorically: “We have zero tolerance.” A few minutes later, she admitted they were so concerned about Joe’s drug taking that they had increased the number of daily welfare observations.

She admitted she was aware that Joe was exploited by other residents, that the level of heroin and crack use in Holmes Road was “high” and that the morning welfare check on 9 August 2023, the day of Joe’s death, did not take place.

Potter appeared horrified by the state of Joe’s room. “Without disrespect to Joe or his family, is it fair to say when you found Joe the state of his room was dire?” The manager said no.

Emma Favata, the barrister for the family, asked whether Joe should have been referred to Change Grow Live, Camden’s integrated drug and alcohol service. The manager agreed he should have been, but denied that this was a failure of the hostel. She said it would have been pointless because he was not ready to engage with services. Catch-22.

The manager was asked about the availability of the drug naloxone, which can reverse an opioid overdose if administered in time. She said the hostel kept it locked in the office and that the only way for residents to get hold of it was through Camden’s drug and alcohol services.

Favata asked the manager: “Do you agree Holmes Road in 2023 was an unsafe environment for someone as vulnerable as Joe?”

“I’m not accepting that,” replied the manager.

Joe’s keyworker at the hostel gave evidence that Joe was known to be “very active in the hostel at night procuring substances”. He was seen knocking on the doors of other residents and would go in for a bit. “I assumed he was picking up drugs from them,” said the keyworker, who also acknowledged that staff were aware Joe “spent all his money on drugs” and that, after a safeguarding incident in March 2023, he was known to be “extremely vulnerable and being exploited in the hostel”.

When the manager and her team had finished giving their evidence, it felt like a long time since Holmes Road had been depicted as a drug-free designer complex with a model support system in place.

Potter concluded that Joe died after taking adulterated heroin. He said there was no evidence he had obtained the heroin in the hostel and that Joe had been made aware by the nurse at his last antipsychotic injection appointment, six days before he died, that synthetic opioids were being sold on the streets. No mention was made in his “findings and conclusion” of the hostel’s failure to adhere to its drug policy, or its reluctance to inform substance misuse services of Joe’s increased drug taking.

Although he did find there was a risk of drug use within resident rooms in Camden-run hostels and the potential for future deaths by overdose, Potter said “nothing could meaningfully be achieved” to address this. “Joe’s engagement with substance misuse services and treatment was sporadic, at best … There were no concerns that Joe lacked capacity to make decisions not to engage with treatment … It is unfortunate that neither healthcare professionals, support workers or Joe’s family were able to secure his continued engagement with the substance misuse support and treatment that was available.”

Potter said he was concerned that the only way to obtain naloxone was by engaging with substance misuse services. He stated that he would write a prevention of future deaths report suggesting naloxone should be made more readily available.

Jude was shattered by the coroner’s verdict. She remains convinced that, as a person with paranoid schizophrenia who was self-medicating with drugs and alcohol, Joe did not have the capacity to make rational decisions about engaging with services. He managed to get to his monthly appointment for his antipsychotic injection only because Jude made sure to remind him, she says. That is why she argued so persistently for him to have a care coordinator. If support is so inconsistent, she says, dependent on the policies and practices of individual boroughs, survival becomes a postcode lottery for the most vulnerable.

Camden is no stranger to homelessness controversies. In November 2023, several tents, most of them filled with belongings, were dumped in the back of a bin lorry and destroyed during the eviction of people experiencing homelessness. The council acknowledged that what had happened was “unacceptable” and promised an “urgent investigation”, but an internal review concluded: “Overall, rough sleeping services … work empathetically and effectively.” Jon Glackin, from the homelessness organisation Streets Kitchen, which filmed the evacuation, calls the review “an absolute whitewash”.

In February, an inquest at St Pancras coroner’s court ruled that 47-year-old Stephen Lovell died in Arlington House, another Camden homelessness hostel, from cardio-respiratory failure caused by cocaine and opioids. Lovell, whose jaw had previously been broken by a member of staff, died on his first day back in the hostel after two months spent getting clean at his sister’s home. Before the inquest, the Lovell family had said that it was impossible for recovering residents to steer clear of the drug culture at the hostel.

While the coroner found little fault with the support services that Joe received, the north Camden rehabilitation and recovery team, part of north London NHS foundation trust, found plenty to learn from his death. After investigating, it sent Jude a “Duty of Candour” report in November, shortly before the inquest. It concluded that the failure to appoint a care coordinator for Joe had left “gaps in care and communication” and that in future there needed to be a more robust system for booking, monitoring and rebooking medical appointments after it was revealed that Joe hadn’t seen his psychiatrist for almost two years.

The report found that Jude should have been offered a formal carers’ assessment as required under the Care Act 2014 and that Camden failed to recognise her role as a caregiver. It also acknowledged that Joe’s care did not fully reflect policy on co-occurring mental health problems and substance misuse and that his needs had been primarily attributed to substance abuse. Finally, it identified gaps in collaboration with the north Camden rehabilitation and recovery team, the drug and alcohol services and Holmes Road. “We are committed to learn from this tragedy and improving our services to prevent similar incidents from happening in the future,” they said in a letter to Jude.

The report could not have been more different in tone and findings from the coroner’s report. While the coroner concluded that it was up to Joe to embrace the support offered, the Duty of Candour report accepted that, because of his condition, he was not always in a position to do so. As for the award-winning Holmes Road Studios, its reputation may be damaged beyond repair.

A spokesperson for north London NHS foundation trust told the Guardian: “We were deeply saddened to learn of Joseph Black’s death, and our thoughts are with his family and loved ones. Extensive reviews have been conducted, both internally by the trust and independently through an inquest. This process has provided us with the opportunity to reflect deeply on Joseph’s death as part of our commitment to continual learning. We have shared these reflections to improve care and support for those who need it. We will continue working closely with all our partners across the NHS and beyond to further this effort.”

In mid-January, I meet Jude near Camden. She is with Alaister, a former resident of Holmes Road who knew Joe well. Alaister, hollow-cheeked with a shock of red hair, says he is doing much better now that he has left the hostel. “I have been a drug addict, I’ve been in the prison system, I’ve been stabbed, but my experience at Holmes Road was worse than all that,” he says. “Before I left, I was suicidal. I’ve never been as desperate.”

He talks about the shortfall in services the hostel provided compared with what it claimed to offer and tells me that two dealers who bullied Joe were finally evicted months after his death. Jude says it still shocks her that the hostel claimed to be helping people towards independent living, yet residents couldn’t even cook in their rooms because the hobs weren’t working.

“Ah, there’s a reason for that,” Alaister claims. “They came round and turned them off because people were using it as a last resort at night-time to cook their drugs and that made the internal alarm go off in the flats.”

Jude listens, open-mouthed and appalled, as if it’s just starting to make sense. “I said to Joe: ‘Why have they turned the hobs off?’ He said: ‘I don’t know.’ So …” She can barely get her words out. “They would rather stop people cooking than deal with the actual drugs problem?” She comes to a stop. “I never believed it was as bad as Joe described. That will always stay with me. That I should have done something.” What could she have done? “Got him out of there,” she says baldly.

A few weeks ago, Black met the justice secretary, Shabana Mahmood, at a conference hosted by Inquest, the campaign group that supports families bereaved by state-related deaths. She told Mahmood that Joe had died in the prime minister’s constituency. This week, she received an email from Starmer’s senior caseworker, asking if there were issues she would like to raise with his office. There are plenty. She hopes to meet the prime minister to discuss them.

I ask what should happen to Holmes Road now. “I think it should be closed,” Jude says. “There’s something deeply wrong and dangerous and disturbing about that place. Nobody should have to live like that and deteriorate and die like that.”

A Camden council spokesperson said: “Our deepest sympathies remain with Joe’s family and friends following his tragic death. Ensuring our residents’ needs are met is a responsibility we take very seriously. We are participating in a Safeguarding Adults Review which is reviewing the support and care Joe received both from the council and its health partners. The learning from this review will be published and will help us work together to continually improve the support that residents receive.

“Camden council’s hostels help support people who are homeless towards full independent living in the community. We will always work alongside individuals to ensure that their choice, control and privacy is respected and central to everything we do. We also work with partners to support people who may have additional needs and ensure that they have access to the services they need. In the case where people have drug or alcohol dependency specifically, our priority is always to reduce the risk of harm to that person, whether or not abstinence is their goal, and to support them to engage with substance misuse services.”

The council declined to comment on how it could reconcile its zero-tolerance drug policy with the prevalence of drugs at Holmes Road. It also declined to say why Joe was not put on a pathway, or what plans are in place to ensure Holmes Road is safer for its residents in future. It admitted that the hobs were still switched off, but insisted this was due to an installation issue and nothing to do with drugs.

A couple of days after my meeting with Jude and Alaister, Jude messages me to say she has been going through more of Joe’s messages. “Joe sent me this, two years before he died, just before he was placed at Holmes Road,” she says.

“I want to get better.

I’m so sick of drugs.

They make me so unhappy.

I don’t want to die young.”

2 months ago

36

2 months ago

36