For more than 50 years it has been at the heart of cultural life in one of the UK’s biggest cities. But research has revealed Manchester’s Royal Exchange building was at the centre of slavery and colonialism, making it “one of the most important locations in the history of global capitalism”.

Since 1973, the building in St Ann’s Square has been home to the Royal Exchange theatre, now staging Liberation (until 26 July), the critically acclaimed play marking 80 years since the 1945 Pan-African Congress – a conference that brought together luminaries of Black liberation, including Kwame Nkrumah, Jomo Kenyatta and WEB Du Bois, in Manchester to progress national independence movements from European rule.

But while the theatre celebrates African liberation, the building, in its former life, was at the heart of European colonial dominance. As a 19th-century trading hall it was the place where “Manchester’s businessmen, industrialists, financiers, and politicians made decisions and deals that transformed landscapes and environments across continents”, research into the building’s history found.

The research, a series of reports involving the University of Manchester (UoM) emerging scholars programme, reveals how the Royal Exchange’s 19th-century subscribers were enmeshed in the enslavement of African peoples, the exploitation of India, the opium trade in China, as well as the development of the economic doctrine of free trade, the birth of the modern city, and the development of liberal politics and economics.

Crucially, the reports shine a light on how African people resisted enslavement, fighting a plantation economy that British elites were at the heart of.

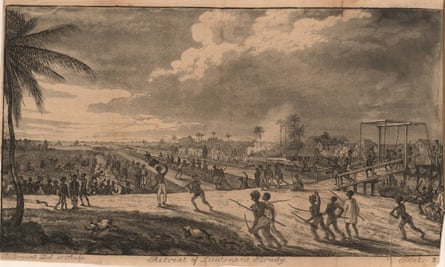

The research looks into the story of Jack Gladstone, an enslaved man on the Success sugar plantation in modern-day Guyana, and his father, Quamina, who led up to 13,000 people demanding freedom in 1823’s Demerara Uprising before it was violently suppressed.

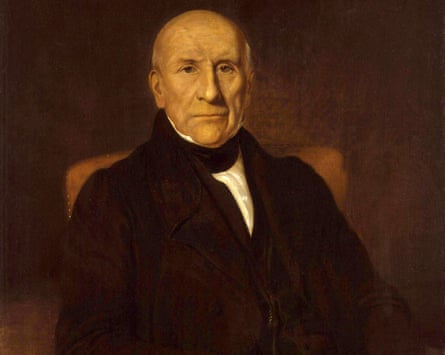

Success was owned by John Gladstone, the father of the 19th-century prime minister William Gladstone, whose wealth derived from enslavement, colonialism and compensation payments after 1833’s Slavery Abolition Act. Members of the Gladstone family played a key role in funding the Royal Exchange building, which was Manchester’s third exchange building, completed in 1874.

The story of Sandy, an African prince who staged a rebellion against enslavement in Tobago in 1770, is also highlighted. Sandy’s rebellion was suppressed with the help of Lord Ducie, a Manchester landowner and Royal Navy officer who sold the land at Market Street on which Manchester’s second exchange, a forerunner to the current Royal Exchange site, opened in 1809.

Ducie, also known as Francis Reynolds-Moreton, was the grandson of Thomas Reynolds, a director of the South Sea Company that formed in 1711 and secured exclusive rights from the British government to traffic and sell 4,800 enslaved people annually to Spanish colonies throughout the Americas.

Facilitated by Ducie’s land sale, the 1809 exchange replaced the first Manchester exchange – which had been built in 1729 by Sir Oswald Mosley, an ancestor of the 20th-century fascist leader Oswald Mosley – creating an “exclusive space” for dealmaking, the researcher Destinie Reynolds found. Mosley Street and Great Ducie Street in Manchester memorialise these family names.

The second exchange professionalised commodities trading at a time when Manchester’s cotton industry was booming – fuelled by crops planted, grown, picked and packed by African people enslaved and transported to the Americas, often by merchants from nearby Liverpool.

Consequently, key, founding players in the second exchange – granted the “Royal” title when Queen Victoria visited in 1851 – were traders in enslaved people, and plantation owners who “used their power and influence to lobby in favour of the slave trade and reduce tariffs on (its) goods … helping to continue its growth”, advancing the “liberal” case for free trade simultaneously, the researcher Beth Carson found.

after newsletter promotion

These men included George Philips, one of the first backers of the Manchester Guardian, the first chair of the second exchange and a partner in Boddington, Sharp and Philips, which owned the Success plantation in Hanover, Jamaica, which relied on enslaved people’s labour.

The research also shows how, after the Slavery Abolition Act, business interests of 19th-century Scottish families integral to the development of the Royal Exchange – the Gladstones and the Arbuthnots – shifted to exploiting Indian indentured workers.

A company in which members of both families were partners was involved in “illegally exporting opium to China to force access to Chinese markets”, as well as exporting Lancashire-manufactured textiles into India, the researcher Aashe Singh found.

In 2021, as it began interrogating its past in more detail, the Royal Exchange launched the Disrvpt programme of events. This included commissioning a poem, Holding Space, from the Manchester writer Keisha Thompson (who is now the programme manager for the Guardian’s Legacies of Enslavement team), which explored the building’s story, in its Great Hall.

The Royal Exchange theatre said of the most recent research into the building’s past: “While reclaiming this space was a radical act, we must acknowledge how this grand empty building came to be here. The building’s very existence is a testament … to the colossal profits of a global cotton economy … one of the most important locations in the history of global capitalism.”

Dr Kerry Pimblott, of UoM, added: “We believe centring such accounts … raises important questions about the legacies of this history in the present and how reparative action can help shape more just futures.”

3 months ago

80

3 months ago

80