A perfect cone of white salt, taller than I am. A low, circular mound of fine, granular soil that rises to meet me, like a bulging ocean swell. Not a speck escapes its edge. An almost hemispherical dome of smooth, compacted clay, whose surface cracked as it dried from the mould it was cast in. The hemisphere stands on the floor like an igloo in the desert. Nearby, a wall of beeswax curves away, with a slightly peppery, honey smell. It leads me to a bristling stockade of tangled branches, foliage and autumnal berries. Inside, it suddenly feels like Christmas, which I doubt is quite the effect the artist was aiming for.

American artist Meg Webster’s sculptures are round things disposed about a circular space that rises to a distant glass and iron roof at the Bourse de Commerce, originally built in the 1760s as a wheat silo and exchange. Later it became the Paris Commodities Exchange, and now the Bourse is home to French billionaire Francois Pinault’s art collection, which numbers more than 10,000 works. Dramatic, oddly vulnerable and beautiful, Webster’s art refers back to minimal art, but its materiality is somehow more primal than that. I last saw her work at the Dia Art Foundation at Beacon, New York. Jessica Morgan, Dia’s director, has curated Minimal, working with Pinault’s vast collection and loans from other institutions.

But this is less curating than wrestling, as much with the huge building as with the art. The Bourse is a kind of Tower of Babel, and Minimal is an odd mixture of solo displays, like Webster’s, and rooms where single works by different artists are bought together thematically, according to the rubrics Light, Balance, Surface, Grid, Monochrome and Materialism. Aside from spaces dedicated to Webster and On Kawara, Robert Ryman, Brazilian neo-concretist Lygia Pape (a compendious show in its own right) and the Japanese Mono-ha group, it often feels a bit rushed and perfunctory.

Things begin well, full of promise and pleasure, as we’re plunged into a room occupied by a marvellous group of small, late paintings by Ryman, whose white aggregated fields of pigment jostle, nestle and nudge the edges of their coloured canvas supports. White sings against rust-red, a dirty khaki, a muted green. Ryman did so much with so little. His art is all about surface and volume, nuance and touch and knowing when to stop. A low, rectangular pile of wrapped white sweets, their cellophane catching the light, sits on the floor below Ryman’s paintings. An iteration of Felix Gonzalez-Torres 1991 Untitled (Portrait of Dad), the quantity of sweets (about 175lb, or 79kg) corresponds to the weight of the artist’s father. Visitors are allowed to help themselves to the mints. Gonzalez-Torres liked the idea that his art would leave a sweet taste in the mouth, to linger like a memory.

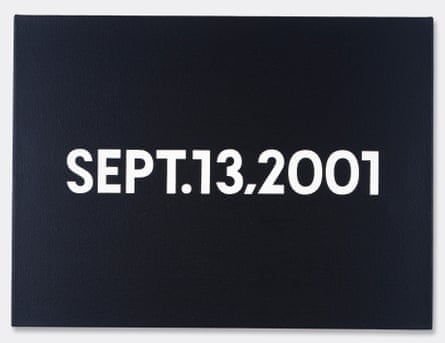

Around the perimeter of the central space antique cabinets hang in the corridor, originally installed here for the 1889 Exposition Universelle. Each contains a single On Karawa Date Painting, in which white lettering and numbers denote the date of the painting’s manufacture. If the Japanese artist didn’t finish by midnight, he ditched the incomplete work. Below the painting, in a box, sits a page from the day’s newspaper, from the city where On Karawa made the painting. Beneath the painting dated 5 October, 1982, a newspaper tells us that Israeli planes have attacked Syrian missile sites. In the box beneath June 20, 1975 there’s a full-page printed advert for the movie Jaws, which opened in US cinemas on that day. The world passes by and we pass with it.

Including works made between the 1950s and the 2010s, by artists working in the Americas, Europe and Asia, Minimal is not a show about minimalism as a movement so much as about the less-is-more, enough-is-enough tendency, and there is an awful lot of it here. This is minimal to the maximal.

From the sparse and somehow dispiriting light works in the basement, where things flash and glow and look a little wan, up to the first floor, where Susumu Koshimizu’s lump of hewn granite sits alone in a wonky, open-topped cube of hemp paper, and his bronze tetrahedrons slant this way and that across the floor as part of a display devoted to the Mono-ha or School of Things movement, we’re crossing not just continents but worlds of thought.

The clunky galvanised steel air-conditioning ducts I passed on the landing are sculptures by Charlotte Posenenske, who worked almost entirely with ready-made industrial sections. On the next floor up I’m surrounded by the quietly humming, repetitively worked paintings of Agnes Martin, in a room devoted to the artist. It also includes a relief in which heavy-duty boat spikes have been drilled into sections of wood, the hexagonal heads of the spikes roughly painted in dark red and white. It is like a weird rejoinder to the delicacy of her repetitive, hand-drawn lines and grids, the infinitesimal shifts in weight and tempo of her art.

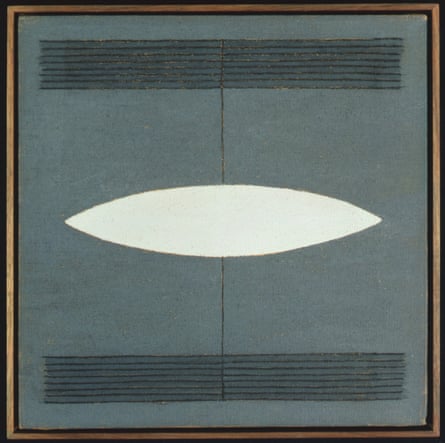

From Martin we go to a more general look at grilles and grids – an Eva Hesse panel of grommets, a Sol LeWitt gridded drawing of arcs and circles, and a great, lone 1966 Bridget Riley painting in which a grid of little black ovoids mess with your retinas and seem to blink back at you as they tilt this way and that, as if there’s too much mental stimulation going on for the brain to cope with. British-Pakistani sculptor Rasheed Araeen’s 16 large open wooden cubes, in red, yellow, blue and green, occupy an alcove, and visitors are invited to re-stack, balance, tilt and configure them in any way they wish.

Quite soon, I’ve stopped caring about the niceties of the thematic displays. I need to take a deep breath and spend time with Pape, whose career in Brazil encompassed not just a huge variety of materials, manners and approaches but also successive movements in Brazilian art, and whose art seemed to cover all bases, minimal or not.

It’s one thing after another, though how amusing it is to see a glum, early 1970s diptych by New York artist Brice Marden, with its smoothed-out waxy surface, in relation to the bright panels of sewn-together, shop-bought cotton fabrics stretched by the late German artist Blinky Palermo.

Things are dangling from hempen cords: stones used in Korean weaving practices that also reference shamanic beliefs, and lengths of wood bundled and suspended from another rope. I guess this is all about balance, like the Richard Serra that leans insouciant and immobile against the wall. Lengths of barbed wire hang from the wall, too, connected to lengths of chain by Melvin Edwards. Senga Nengudi’s bulbous and pointy transparent vinyl bags, partly filled with dyed water, flop and bulge from heavy ropes, hinting at bodies that sprout and leak and won’t behave.

Ryman reappears, with works more casual and more eccentric than those on the ground floor, and I’m dying to come across something by Cady Noland, but she’s not here. There’s no Bruce Nauman, and no Robert Morris. More ropes and chains snake over the floor, in Maren Hassinger’s River, which intends to evoke the despoliation of nature and the journeys that took enslaved Africans to the Americas.

What links these objects and images and what divides them? Can we look at them all the same way or must we approach them differently? It is very difficult not to just clock things, tick the checklist and keep on climbing the stairs and circulating, in pursuit of a conclusion that is endlessly deferred. The minimal is always with us.

2 months ago

61

2 months ago

61