It is May 2025, it is 4am, and I am sitting up in bed, sleepless, looking out at a huge moon illuminating the still world.

Eighty-five years ago, in 1940, a silently weeping seven-year-old lay on a cracked leatherette sofa in urine-soaked pyjamas, looking through an alien window, praying that that same moon would protect my mum and dad from the killer bombs falling in London.

That morning, my dad had tied a label to my gas mask strap with my name and address written on it, and waved me off from the platform barrier after making me recite, yet again, my identity number in case I became detached from my group of evacuees. It was CJFQ 29:4; my old brain has forgotten many things, but that number is deeply engrained. The details of what happened next are confused, until the door at the bottom of the stairs in my billet was slammed closed by my unwilling hosts, and I lay trembling on that settee. As an adult, my first reaction to everything is fear, which I put down to my wartime childhood, along with my ability to survive. After two runaway escapades I was allowed to return to London, preferring bombs to bullying locals.

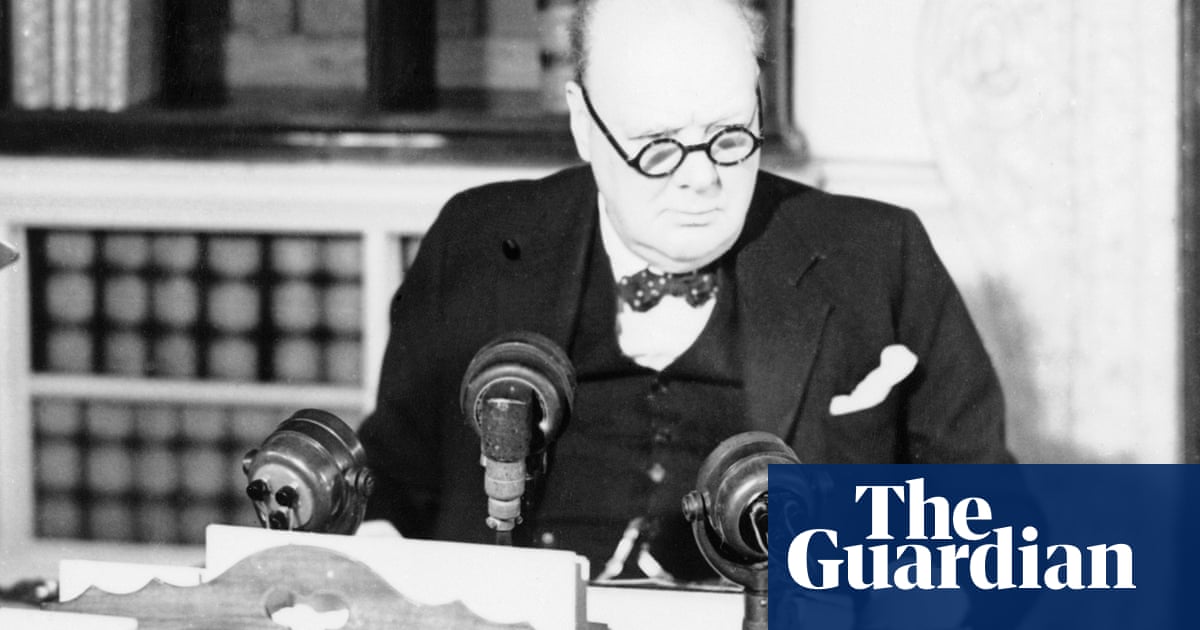

This month, we are commemorating the 80th anniversary of VE Day, and I worry that we will turn it into a yet another jingoistic celebration of the second world war. Yes, in 1945 we were relieved that the bombs and doodlebugs and rocket weapons had stopped, and we heard there was fun going on in the West End of London – but where I lived it was less jubilant. The war there felt far from over: we were still waiting anxiously for the return of the young lad next door from the rumoured horror of a Japanese prisoner of war camp, and many of my friends were trying to accept as fathers strange men they barely knew. The unspeakable details of the Holocaust were being revealed, and I imagine the grownups were utterly exhausted and often grief-stricken. For five years, they had lived under the threat of occupation. Churchill said we would fight them on the beaches and never surrender, but he did not deny that we could be invaded. In fact, it was a miracle we were not. And that threat is what the grownups lived with, and presumably, being unequipped, knew they could not withstand.

I remember in the early days of the war asking my dad about some concrete blocks that had appeared on the pavement, and some black metal cylinders along the kerb. He explained, somewhat unconvincingly, that the blocks would be dragged into the road to stop the Nazi tanks, and the cylinders would be lit to make a smokescreen that would, together with the barrage balloons filling the skies, impede their planes. Being close to some weapons factories and the docks, our area around Bexleyheath was the scene of many dogfights between Spitfires and Nazi planes. There was even a searchlight and mobile ack-ack gun stationed on the path behind our house. When we were in our garden air raid shelter, the noise of that gun certainly scared the wits out of us, if not the Germans.

Because I now deeply fear the dangerous signs of history repeating itself, I want everyone to remember that war is terrible. On VE Day 1945, the world was looking at the complete destruction of many cities, some by us. Tens of millions of people were dead or homeless. It was hard to wholeheartedly rejoice in May 1945.

Sorry to be a spoilsport. I actually hope everyone comes together and has a lovely time on the 80th anniversary. I think I probably quite enjoyed myself in 1945. The kids had a street party tea, with junket and blancmange (whatever happened to them?), with evaporated milk as cream, and a few chocolates. A feast in those strictly rationed days.

But what I most remember is when the tables were removed, and someone brought out a wind-up gramophone and put it on the garden wall. The grownups did some stately ballroom dancing. Holding one another in their arms! Clinging to one another. I even saw my dad kiss my mum on the forehead. Unheard of behaviour. Were they expressing relief at being near the end of an appalling few years? Or were they giving one another strength to face the inevitable struggle to dress the mental and physical wounds of war, and build the better, fairer, more peaceful world they wanted to create?

Now, our beautiful planet is under threat in many ways. History shows that the solution is definitely not to be found in autocratic leadership. Let us aim to unite the available worldwide wisdom to tackle the global crises together. Time is running out.

This week, the moon reminded me of a wartime child who, along with her contemporaries, will soon be gone, taking our painful memories with us. I look back with some pride at the way that generation of adults survived, drained but determined to make the world a better place. And they did.

Please God, don’t let us betray them. We must not forget and we must never let it happen again.

-

Sheila Hancock is an actor and a writer

15 hours ago

12

15 hours ago

12