More than 100 years ago, a Māori woman packed up her life as a tour guide and entertainer in New Zealand and set off for England, where she would soon make history by enrolling at Oxford university.

In a tragic turn, Mākereti Papakura – believed to be the first woman from an Indigenous community to study at the university – died just weeks before completing her thesis, and in the decades since, her family has fought to have her degree recognised.

Last week, that recognition was granted. In front of more than 100 family and iwi (tribal) members who travelled to Oxford to witness the honour, Papakura was posthumously awarded an MPhil in anthropology for her work documenting the life, language and customs of her Te Arawa people.

Papakura’s descendant, June Northcroft Grant, was teary as she accepted the certificate from the university’s vice-chancellor.

“It was very surreal. I had to collect myself because I was getting emotional and didn’t want to do ugly crying on TV,” she said.

Watching a livestream from the nearby Natural History Museum, dozens of her extended family launched into a thunderous haka as a mark of honour.

Born in New Zealand’s Bay of Plenty region in 1873, Papakura grew up during a time of significant change for Māori, including the rapid loss of land, language and Indigenous knowledge as the grip of colonisation tightened.

She was raised by her elders from Tūhourangi and Ngāti Wahiao, two Arawa subtribes, around the geothermal village of Whakarewarewa. The village is near the city of Rotorua, famed for its boiling mud, simmering streams, and geysers that gush from the Earth’s crust.

It was while working as a guide near Rotorua that she attracted attention during a royal visit in 1901, and later became a model, featured on a range of postcards and in photoshoots.

A decade later, Papakura travelled to England with a cultural performance tour group that went bankrupt, with many of the participants staying to work or marry locals.

She returned to Rotorua only briefly before marrying a wealthy Englishman, Richard Staples-Browne. She moved to Oxfordshire where she enrolled at the university and befriended the anthropologist TK Penniman.

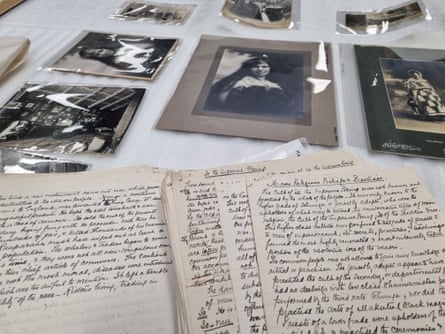

In tight cursive, she spent years writing her detailed knowledge of genealogy, histories, language and customs on thousands of sheets of paper, recalling the ancient traditions of the Arawa people.

Remarkably for the time, it was a detailed work about Indigenous people, by an Indigenous woman.

But Papakura died in 1930, aged 56, just three weeks before her thesis was due.

Penniman would later publish the thesis as a book, The Old Time Māori, which her descendants say is as relevant today as ever. Grant said it has been used by Māori trying to reclaim their language and ancestral knowledge, even proving useful in legal land claims.

“We found a lot of information about our lands in the village. All the caves and the geysers,” she said. For nearly a century, the fact she didn’t have her degree proved something of a sore point.

“Ninety-five years, why did it take so long?” Grant asked. “We’ve been quietly and patiently telling her story.”

At a reception with the family among the displays at Oxford’s Pitt Rivers museum on Saturday, the vice-chancellor, Prof Irene Tracey, said it was an honour to finally recognise Papakura’s influence as a scholar.

“I could not think of a person – globally, historically – more worthy of that honour,” she said. “At a time when so few women came to Oxford, so few women did degrees.”

The delegation of Te Arawa spent nearly a week in the UK, attending a range of ceremonies, performances and other events.

Anthony Wihapi, an elder who was among the delegation, described a feeling of “amazement”. “It’s existed for 900 years and I’m told this is one of the first times they’ve awarded a posthumous degree. It’s an incredible thing for our [family] to be proud of.”

Part of the delegation’s tour included presenting a gift of a two-metre carved figure, or pou, intricately chiselled into a slab of tōtara wood.

Papakura and her concert party brought the pou to England in 1911, during their first visit.

“They used the whakairo (carving) as a facade behind them and they would perform in front of it,” said Rob Schuster Rika, a carver who is also a relation of Papakura.

It stayed in the UK, passing through various owners and uses – including as a work bench – before falling into a state of disrepair, Rika said. Last week, after careful restoration by Rika, Te Arawa gave the pou back to the British people at the Stratford headquarters of the British Council, where it will go on display.

“It was the rejoining of the pou, or a people, and revitalising Maggie Papakura’s [work] to share our culture to the world,” he said.

2 months ago

54

2 months ago

54