It’s a story to keep Edinburgh fringe dreams alive. On their own dime, Xhloe Rice and Natasha Roland rocked up at the festival in 2022 to try their luck. The US duo’s queer western clown show, And Then the Rodeo Burned Down, went from an audience of seven to winning a Fringe First award and selling out. They repeated both feats with another two-hander in 2023. And another in 2024. This summer, the best friends – who perform as Xhloe and Natasha – will stage all three prize winners in Edinburgh.

That is, if they can afford to get there. “We haven’t bought our flight tickets yet,” says Rice, highlighting the grim economic truth behind fringe success. “We have to wait until we make a bit more money.”

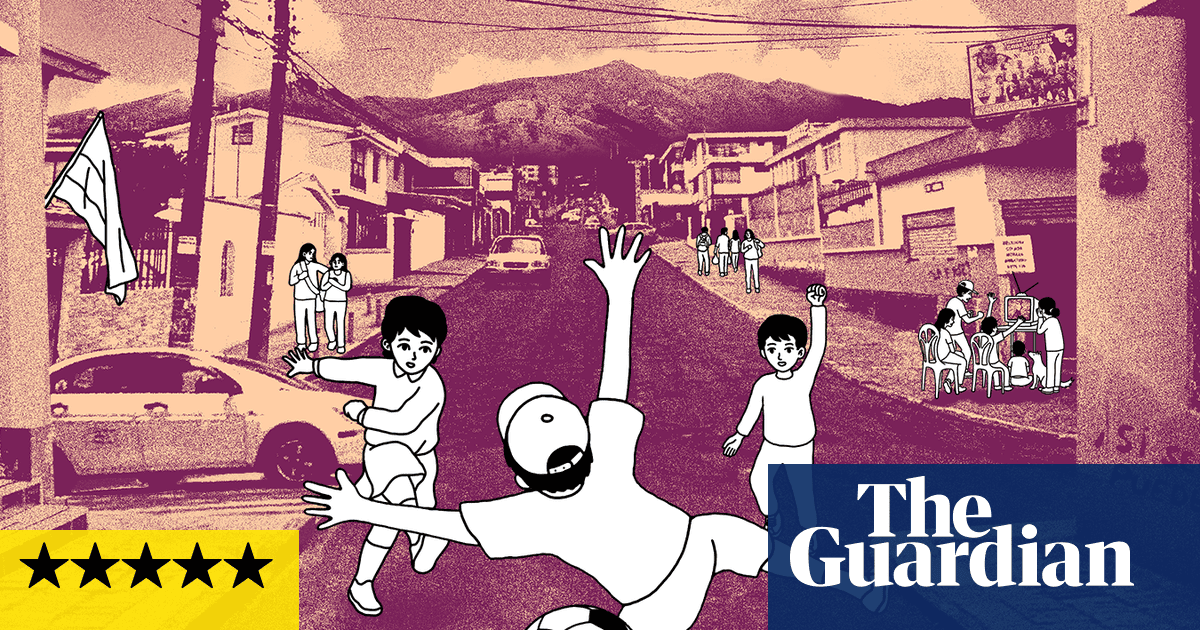

We meet at Soho theatre in London where the pair are performing their second hit, What If They Ate The Baby?, and their most recent one, A Letter to Lyndon B Johnson or God: Whoever Reads This First. Both shows playfully consider Americana and gender using absurd comedy, distilled dialogue and striking choreography. Each has a light touch yet ambushes your emotions. The former is a melodrama-cum-horror detonating 1950s domestic ideals, with the pair wearing pastel frocks and serving neon green spaghetti. In the latter they portray muddy scouts, in a Boys’ Own caper, venturing into tragedy.

The scouts, Ace and Grasshopper, await a visit from the eponymous US president who served from 1963 to 1969. The Beatles’ Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da gives the show its jaunty rhythm but war looms on the horizon. “We don’t say ‘Vietnam’ ever in the show,” points out Roland. “We don’t say ‘1950s’ or ‘housewives’ in Baby … We don’t like to spoon-feed every detail. As writers we usually prefer giving the audience the responsibility to fill in the gaps.”

Talking a mile a minute, Rice and Roland have developed a hive mind and frequently finish each other’s sentences. With A Letter to LBJ, they wanted to explore “mythical boyhood”, says Rice. “We felt like we missed out on something because we were raised girls.” To be a boy, they were taught, “was all about skinning your knees and jumping fences and playing baseball. And you had no troubles. It’s kind of insidious and speaks to the myth of a great former America that doesn’t exist any more and it’s weaponised.” Both were girl scouts. “The boys did archery, knot-tying, camping.” And the girls? “Sold cookies,” says Roland. “Made friendship bracelets,” adds Rice. “But I want to shoot an arrow!” protests Roland.

The show was almost a letter to Richard Nixon “but he has a flatly negative connotation”. Johnson intrigued them as he had a more complex legacy. Defined by the conflict in Vietnam, he made considerable achievements in social welfare and civil rights. Ace and Grasshopper start out simply “playing good guys and bad guys” but the theatre-makers delve into grey areas. “America is the good guy – you’re told that as a kid,” says Roland. “Then you hit a certain point where you have your own thoughts and it’s maybe … ‘Oh, we’re not?’”

As president, Johnson championed the Kennedy Center, breaking ground for it with a gold-plated spade in 1964 and heralding the government-funded, bipartisan venue as “a living force for the encouragement of art”. Last month, Donald Trump ousted its chair to preside over the board himself and ensure, he declared on social media, “no more drag shows, or other anti-American propaganda”.

As fringe theatre-makers, the pair weren’t planning on playing the venerable venue any time soon, but the Kennedy Center is “representative of culture in America” says Rice. What happens at the top “trickles down”, adds Roland. “When you start to govern what artists are allowed to make, that’s dangerous territory.”

To save money and create A Letter to LBJ, the pair moved back into their family homes. Both have fathers who were in the military. “Most of our childhoods were in post 9/11 America – one of the most nationalistic times in recent US history,” says Rice. The friends grew up near Baltimore, Maryland, and became inseparable at school, where Roland was Rice’s tour guide on orientation day. Studying acting at different universities in New York, they collaborated on a “rogue” production of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead at Rice’s college. “We did it secretly,” grins Rice. “I was sneaking people in. We lit the whole thing with 100 desk lamps.” “Such a fire hazard,” tuts Roland.

The Tank, a nonprofit theatre in Manhattan, became their artistic home. But “we were having a hard time making a name for ourselves in New York. Or just getting eyes on us,” says Roland. They crowdfunded for Edinburgh, saving what they could from daytime teaching jobs (maths for Rice, biking and skateboarding for Roland) and rehearsing Rodeo from 10pm until 2am. The show – a tricksy comedy about a clown, his shadow and a cowboy – had a meta subplot about their fight to get it finished. This was born from bleary rehearsals, where Roland felt: “I want the energy to give to the art I want to make.”

As a duo, they’re a “cheap date” for theatres, says Rice. With minimal set and props, “most of our shows fit in a duffel bag”. They thought the majority of artists at the fringe would be in a similar position to them but were surprised by how “a lot of the shows getting recognition or reviews had funding from an arts council or huge companies”.

The pair create their own costumes, sound design and choreography. The long-term plan is “to do this, but bigger” says Rice. “And maybe not have to share a room?” Until then, they’re juggling two shows in London and taking all three back to Edinburgh. “We’re going to drink a lot of vitamin C,” laughs Roland. After all, it’s not their first rodeo.

1 month ago

26

1 month ago

26