A lack of regulation over the use of expert witnesses in English courts could be leading to miscarriages of justice, senior politicians, lawyers and doctors have said.

The former attorney general Dominic Grieve and the former justice secretary Jack Straw were among those to tell the Guardian that criminal and civil trials were sometimes hanging on evidence by self-appointed “experts” who could lack relevant knowledge.

Grieve warned that although experts were supposed to be independent, they often came across as being “hired guns”.

“Expert evidence is clearly critical, legitimate and in some cases can be absolute clinchers,” he said. But when dealing with issues “at the limits of human scientific knowledge and understanding”, expert witnesses could make people feel comfortable about making decisions when “quite frankly, the evidence isn’t there”, he said.

Concerns over the use of expert witnesses have been raised in relation to the case of Lucy Letby, the neonatal nurse convicted of murdering seven babies. Lawyers appealing against her conviction argue that the expert evidence presented at her trial was flawed.

Expert witnesses were also criticised during the Post Office scandal, where subpostmasters were convicted of stealing based on evidence from IT experts that has been subject to criticism.

Expert witnesses are used in both criminal and civil courts to give information and opinion on matters relevant to the case that would be considered outside the knowledge of a judge or jury.

They are supposed to give an objective and unbiased opinion, according to guidelines from the Crown Prosecution Service, and can be instructed by the prosecution and the defence. But there are no formal controls on who can describe themself as an expert or training required to ensure they understand legal procedure.

Jack Straw, a former justice secretary, said there was a “nagging worry” that expert witnesses were not being properly regulated.

He said courts often encourage both sides to agree on using one expert witness, to save on time and costs, but “in my view this emphasises even more the need for there to be better regulation of expert witnesses” to ensure reliability.

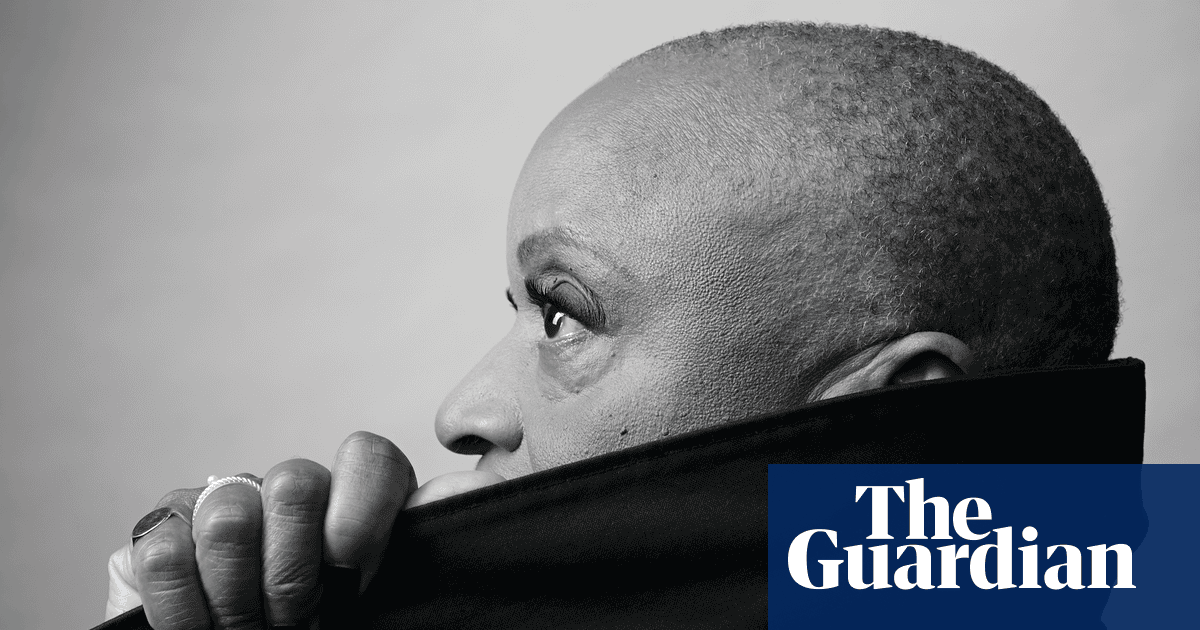

Nazir Afzal, a former chief crown prosecutor for north-west England, said there are “a number of issues” with the system.

He said it would generally be up to a judge to decide whether somebody has the relevant expertise, which becomes more complicated if the area of expertise is related to “lived experience” rather than science. With international experts, he said, it may also be difficult for a court to verify their qualifications.

He also said there were issues with “expert shopping”, where lawyers will consult different experts until they find one who will say what they need them to.

The law firm Bond Solon offers expert witnesses training, and also runs an annual survey that looks at improving standards of expert evidence.

More than a third of experts who responded to the 2024 survey said they had experienced “hired gun” experts in their field in the past year, referring to people who provide “evidence to substantiate the opinion preferred by the instructing party”. One in four also said they had been pressured by solicitors to produce biased opinions.

Simon Berney-Edwards, the chief executive of the Expert Witness Institute, a not-for-profit membership body for expert witnesses which provides training, vetting and a directory, said there “is no bar set” to ensure people not only have the correct qualifications, but that they understand legal procedure.

“There is no thing that says [expert witnesses] have to be registered with their professional body, or with any regulatory body. The onus on vetting the quality of their expert remains very much with the legal team,” he said.

“Many people will say that they’re doing expert witness work but haven’t had one bit of training. Where you’ve got people that don’t understand what they’re doing, that’s where you get the problems, the possible miscarriages of justice.”

Expert witnesses are paid for their time, and although in criminal cases – particularly those funded via legal aid – it is not always very lucrative, people can make large sums in civil and medico-legal work.

Prof Sir Norman Williams, a former president of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, carried out a government commissioned review into gross negligence manslaughter prosecutions against medical professionals in 2018 that found widespread concern about expert witnesses.

The review found issues with “the quality and consistency of opinion provided by healthcare professionals acting as expert witnesses” that may not be uncovered until trial or appeal, and made recommendations for more training.

“Ideally one would like to see a system that was better regulated, but I can’t see that happening easily,” Williams said.

“You have to be somewhat concerned that problems [highlighted in the review] can recur, because some cases are very complex, they’re difficult for juries to appreciate. If all the factors aren’t taken into consideration, there could be miscarriages of justice.”

Jonathan Lord, an NHS consultant gynaecologist and co-chair of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists abortion taskforce, said there is concern among medics about some witness evidence that has come before the courts.

“They are hired by one side, not the court, and many have substantial earnings from this work, so conflicts of interest that would not be acceptable in other professional spheres are embedded into the system,” he said.

“While they are supposed to be neutral, given the large payments involved and the need to be called and engaged again in the future, it’s hard to be reassured that bias doesn’t creep in.”

3 months ago

113

3 months ago

113