The prolific Russian composer Rodion Shchedrin, who has died aged 92, displayed a disconcertingly diverse range of styles, and a political agility useful in sustaining a career in the Soviet Union. He was also one of the earliest Soviet composers of his generation to make a mark in the west.

His First Concerto for Orchestra (1963) was taken up by George Balanchine, which prompted Leonard Bernstein to commission the succinct Second Concerto for Orchestra (The Chimes, 1968) for the New York Philharmonic. The Third Concerto (Old Music for Russian Provincial Circuses, 1988) was written for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Lorin Maazel; the Fourth Concerto (Round Dances, 1989) was premiered by the Tokyo Symphony Orchestra; and the Fifth (Four Russian Songs, 1998) was a BBC Proms commission. The last two were first recorded by the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra under Kirill Karabits.

Initially Shchedrin’s artistic reputation depended on his ballets for the Bolshoi theatre, Moscow, starring his wife, Maya Plisetskaya, one of the greatest dancers of the age; they married in 1958. His deft arrangement of Bizet – Carmen Suite (1967), highly successful with concert audiences – was followed by balletic reimaginings of literary classics including Anna Karenina (1972), after Tolstoy, and The Seagull (1979) and The Lady With a Lapdog (1985), both after Chekhov.

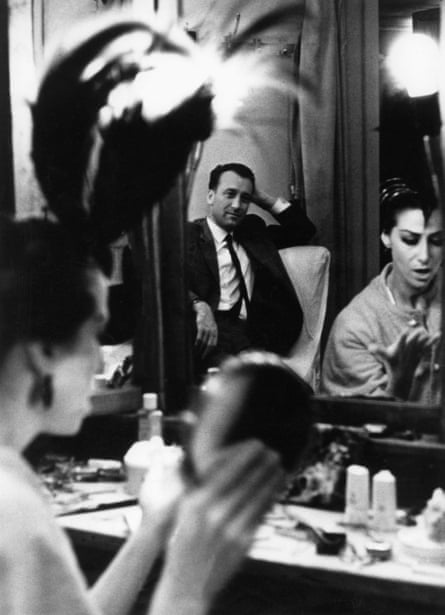

From his youth, Shchedrin was passionate about the theatre, fascinated by what he described as “the sweet and fascinating poison you feel when you go backstage”. His early opera Not Love Alone (1961) held the Soviet stage for several decades and, as with ballet, he enjoyed composing operas drawn from Russian texts including Dead Souls (1976, after Gogol), Lolita (1992, after Nabokov, a commission from Mstislav Rostropovich), and his “choral opera” based on the writings of the 17th-century mystic Avvakum, Boyarina Morozova (2006). This is an austere essay in the neo-primitivism favoured by Russian composers from Stravinsky, Prokofiev and Shostakovich to the present day.

The range of Shchedrin’s non-theatrical music is equally varied, from his 1969 oratorio Lenin Lives in the Heart of the People (which does what it says on the tin) to perhaps one of his strangest and most perplexingly “avant-garde” pieces, Musical Offering (1983), a vast and bleakly dissonant homage to Bach for organ, three flutes, three bassoons and three trombones, which he later softened and “shortened” to a mere two and a quarter hours. His orchestral works – the concertos for orchestra, for solo instruments and three numbered symphonies among many others – are equally unpredictable.

His Second Symphony (1965), for instance, consists of a sequence of 25 interlocking orchestral preludes. In 1974 he famously gave the premiere of his Third Piano Conerto in a concert in which he also played the First and Second, and went on to write three more.

A glutinously sinister set of orchestral variations is titled Self-Portrait (1984). There are jazz-influenced moments in Shchedrin’s earlier scores, and some of his later music for chamber ensemble shows him toying with influences from American minimalism.

In public encounters he could be provocative and teasing. Of one of his pieces, he said: “I wanted to capture the sensation of bathing in cold water on a hot day. And the feeling of the water on one’s skin!”

When Rostropovich invited him to compose a concerto, the great cellist was astonished when he opened the score: “But the solo part is all harmonics! It’s all quiet!” Shchedrin’s music suggests a complex and deceptive figure: a shapeshifter, perhaps, and not always a reassuring one.

Born in Moscow , Rodion was the son of Concordia, a financial administrator at the Bolshoi, and Konstantin Shchedrin, a composer and musical theory teacher. A chorister as a boy, Rodion went to the Moscow Conservatory to study composition with Yuri Shaporin and piano with Yakov Flier.

He also attended postgraduate classes by Shostakovich, who showed his students music – especially by Stravinsky – that was otherwise not available or accessible in those restricted days. When a BBC interviewer asked Shchedrin about the effect on composers of Khrushchev’s cultural thaw in the late 1950s, he replied: “In those days every new name we heard – Stockhausen, Boulez, Xenakis – flashed like lightning in a storm!” Subsequently, he himself taught at the Conservatory.

Early on he found his way into film, where he worked with the director Aleksandr Zarkhi, and at the Bolshoi theatre his ballet The Little Humpbacked Horse (1955) made a strong impression. Almost immediately after he married Plisetskaya, seven years older than he was and already world-famous, they became the golden couple of the Bolshoi, living in later years in an apartment of great splendour in the centre of Moscow, filled with artworks and memories of Plisetskaya’s glorious career.

In 1968 Shchedrin declined to sign an open letter supporting the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Soviet troops, and he was not a Communist party member. Nonetheless, in 1973 he succeeded Shostakovich as chair of the Composers’ Union of the Russian Federation, and for more than a decade wielded considerable influence, at times to the noticeable discomfort of his senior colleague Tikhon Khrennikov, first secretary of the Composers’ Union of the USSR, the overall organisation.

Even before the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Shchedrin and Plisetskaya spent more and more time abroad, later taking Lithuanian and Spanish citizenship, and living for the most part in Munich.

Plisetskaya died in 2015.

1 month ago

60

1 month ago

60