After the first night of his play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead at the National Theatre in London in 1967, Tom Stoppard awoke, like Lord Byron, and found himself famous. This new star in the playwriting firmament was a restless, questing bundle of contradictions. Stoppard wrote great theatre because, primarily, he wrote argumentative and witty dialogue. Writing plays, he said, was the only respectable way of contradicting oneself. His favourite line in modern drama was Christopher Hampton’s in The Philanthropist: “I’m a man of no convictions – at least, I think I am.”

Stoppard, who has died aged 88, was always patient about the demands of the publicity machine, though just as deeply averse, like Harold Pinter, to discussing his work, or indeed his private life, in public. Yet what one critic called “the hypnotised brilliance” of his English prose and dialogue fascinated journalists, as well as the public, who thought of Stoppard as “a bounced Czech” (he described himself thus, having been born in Moravia) with a showman’s flair and a curatorial devotion to his adopted language on a par with Conrad’s, or Nabokov’s.

The theatre critic Kenneth Tynan, acting as Laurence Olivier’s literary adviser at the National, had telegrammed Stoppard asking for a script of Rosencrantz after it opened at the Edinburgh festival in 1966 to a rave review by Ronald Bryden in the Observer. The play, in which the two courtiers are seen flipping a coin that always comes down on the same side before being sucked into the “background” action of Hamlet’s tragedy, had come through a few one-act pre-incarnations, been toyed with by the Royal Shakespeare Company and was produced in Edinburgh, finally, by the Oxford Theatre Group in a student production.

Stoppard followed Rosencrantz with two plays of reputation-enhancing pyrotechnical brilliance: Jumpers (1972), in which a moral philosopher writes an essay on the existence of God against a backdrop of acrobatic logical positivists and the death of romance with the moon landings; and Travesties (1974), a collision of surrealism and Soviet realism enmeshed in a performance of The Importance of Being Earnest in Trieste in 1917, as unreliably recalled by a minor consular official engaged in a dispute with James Joyce over the cost of a pair of trousers.

At this point, Tynan wrote a brilliant profile, paralleling Stoppard’s career and creative talent with those of his Czech near-doppelganger Václav Havel, who, like Tynan, became a close friend. As a young journalist himself in Bristol in the late 1950s, Stoppard considered himself miscast as a theatre critic because he distrusted his subjective responses: “I never had the moral character to pan a friend. I’ll rephrase that. I had the moral character never to pan a friend.” He said that he wrote only for posterity, yet admitted, a few years later, that he was “mostly, unconsciously, trying not to cooperate with posterity”.

West End plays such as Night and Day (1978), about journalists covering war in Africa while the closed shop issue rages at home (“I’m with you on the free press, it’s the newspapers I can’t stand”) and Hapgood (1988), making connections between espionage and quantum physics, and featuring his first female lead role (taken by his sometime partner and muse, Felicity Kendal), were no less demanding, or rewarding, than the larger-scale canvases at the National Theatre, both masterpieces, Arcadia (1993) and The Invention of Love (1997, one sprung from a response to the chaos theory in two time scales, the other taking the story of the poet AE Housman as a study in melancholia and unrequited love.

Then there were his fizzing, joyously free-wheeling 80s National Theatre adaptations of middle-European classics by Arthur Schnitzler, Johann Nestroy and Ferenc Molnár (Undiscovered Country, On the Razzle and Rough Crossing – the last of which translated a 1924 comedy in a castle to a musical play rehearsal on a transatlantic liner in the 30s); as well as his ambitious trilogy, The Coast of Utopia (2002), again for the National, examining the seeds of the Russian revolution in the lives of its 19th-century idealists and, in 2006, his most direct dramatic statement on the Velvet Revolution in his native country, Rock’n’Roll (2006) at the Royal Court, with Havel and Mick Jagger among the first night audience.

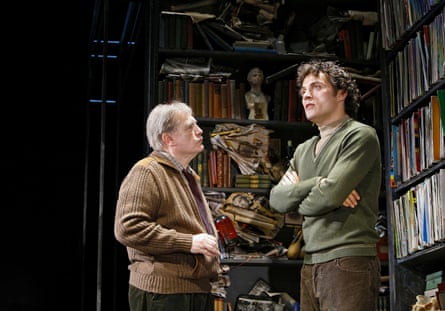

Stoppard was sometimes viewed as a Wildean anomaly whose dramatic instinct was ruled more by head than heart. His earliest and most important director, Peter Wood, encouraged him to bring the relationships in his plays “out of the fridge”. He certainly did this in The Real Thing (1982) in which a successful playwright, Henry, is driven to exasperation by his actor wife appearing in the leftwing drama of a playwright who can’t write for toffee. “Save the gerund, screw the whale” jeers Henry, launching into one of the great speeches of modern drama about a cricket bat sprung like a dance floor, designed to despatch balls long distances with minimal effort: “What we’re trying to do is to write cricket bats.”

Politically, Stoppard was a member of the libertarian right, a conservative with a small “c”. He was loth to find fault with a Britain where free speech and human rights were largely respected because he knew at first hand of countries, and regimes, where such privileges were rare, and all of his plays can be viewed in a wider political spectrum than their immediate setting. Like Oscar Wilde, he was a subversive artist with an aesthetic credo and, also like Wilde, made sure that his everyday conversation was well-turned and funny. At 70 years old, he told a journalist that he used to have a good memory, but couldn’t remember when he lost it.

He seemed always “plus Anglais que les Anglais” (the point being made in French pleased him), living in a Palladian house in Iver, Buckinghamshire – when he worked with André Previn on a piece for actors and full orchestra about Russian dissidents, Every Good Boy Deserves Favour (1977), Previn dubbed him “Iver Novello” – collecting British watercolours and indulging hobbies of fly fishing and cricket, a game he played with enthusiasm as a batsman/wicket keeper in Pinter’s Sunday scratch team.

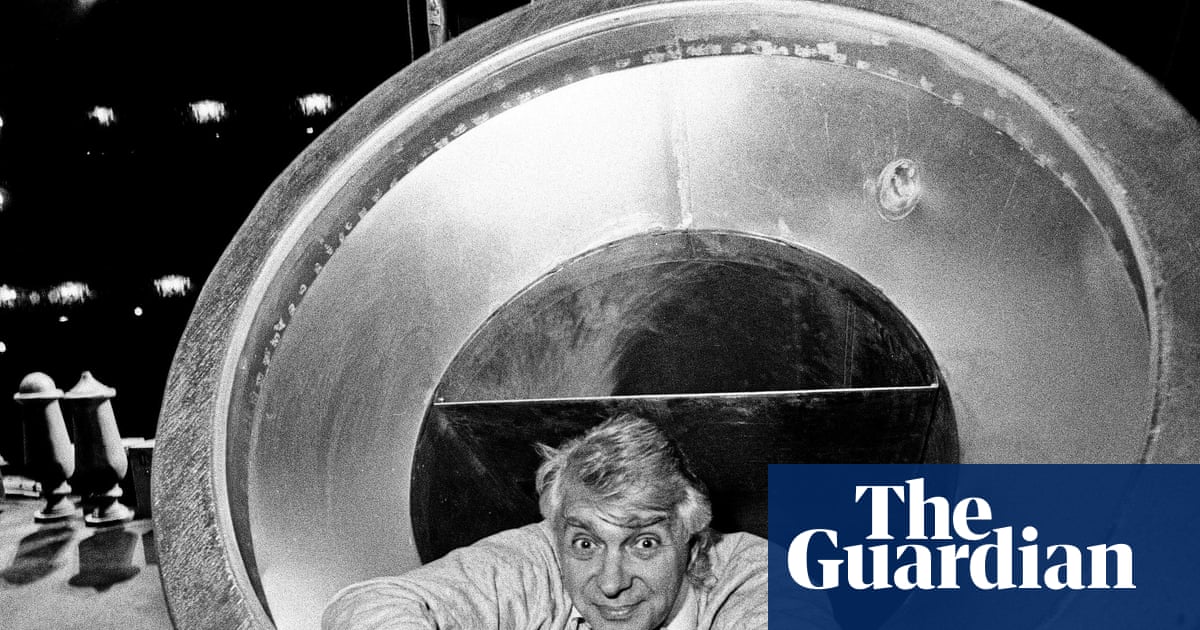

A tall and strikingly handsome man, with a long, bloodhound face, a thick tangle of hair and a casually assembled wardrobe of expensive suits, coats and very long scarves, Stoppard cut an exotic, dandyish figure, a valiant and incorrigible smoker who moved easily in the highest social and academic circles, a golden boy eliding into middle-aged distinction and never losing the thick, deliberate accent of his origins, even though he never spoke Czech. He carved out his career in his own always carefully chosen words.

He was often thought to be “too clever by half,” but never patronised audiences by talking down to them, even if they had to work hard to keep up. He was the source of two fictional characters: in Clive James’s 1983 novel Brilliant Creatures, Tim Stripling “wrote plays at such an intellectual altitude that only a symbolic logician could follow the plots,” while Peter Nichols’ more double-edged portrait of a wealthy playwright in A Piece of My Mind (1987) was named, with a dig, Miles Whittier, and was the envy of the play’s hero.

It seemed odd in someone so culturally and intellectually alert that Stoppard should not have been fully aware of his Jewish extraction until well into his middle age and then did not write anything about it until Leopoldstadt, which opened at Wyndham’s theatre in London in February 2020 and was, he said, to be his last play. This sombre epic, quite uncharacteristic of the most dazzling and entertaining playwright of our times, groaned under the weight of Stoppard’s sudden solemnity, but was salvaged in final scenes of heart-stopping beauty and resolution.

Stoppard was born Tomáš Sträussler in Zlín, in south eastern Moravia, in what was then Czechoslovakia (and is now the Czech Republic). He was the younger son of Eugen Sträussler, one of seven Jewish doctors employed by the Bata shoe company, and his wife, Marta (nee Becková). With help from Bata colleagues, the family left for Singapore in 1939. When the Japanese invaded in 1942, Tomás and his brother, Petr, and mother were placed on one of the last boats bound for Australia, but were diverted by war at sea and ended up in Mumbai. His father escaped as Singapore fell but was killed when his boat was attacked. After the war, Marta married a British army officer, Kenneth Stoppard, in Darjeeling, where she managed a Bata shoe store, and the new family came to the UK in 1946. Tom’s four grandparents, and many of his parents’ generation, he discovered later in life, died in the death camp at Terezín.

On being demobbed, Kenneth – not a very nice man, according to Hermione Lee’s definitive 2020 biography of the playwright – worked as a machine tools salesman. Tomáš (now Tom) and Petr (now Peter) went to the Dolphin school in Nottinghamshire – Peter would become a successful accountant, looking after his brother’s financial affairs in later life – and then to a minor public school, Pocklington, in Yorkshire in 1948. The following year, their mother gave birth to a third son, Richard. Tom loathed Pocklington and hurried down to the new family home in Bristol, where he started work on the Western Daily Press in 1954, submitting plays to BBC Radio and writing for the radio soap Mrs Dale’s Diary. By the end of the 50s, he was writing features and reviews for the Bristol Evening World.

His beat as a reporter took him to the Bristol Old Vic where, in the 1957-58 season, he saw Peter O’Toole play Hamlet and Jimmy Porter in Look Back In Anger. He was hooked. And he played cricket with O’Toole. Two years later he found himself sitting behind Pinter at a revival of The Birthday Party and, tapping him on the shoulder, said, “Are you Harold Pinter, or do you just look like him?” Pinter said, “What?”

He had plays accepted by the BBC on radio and television, short stories bought by Faber and a novel commissioned by Anthony Blond, Lord Malquist and Mr Moon (1966), which contains many future themes and tropes.

When Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead opened at the Old Vic, Harold Hobson in the Sunday Times dubbed it the most important event in the British professional theatre of the past nine years (ie, since Pinter’s The Birthday Party). The influence of Samuel Beckett was palpable, but this was the first play to use another as its décor, and there were elements of Kafka and European absurdism; anyone who ever thought that Stoppard was an apolitical writer from the outset, said Irving Wardle, only had to see a stunning Russian/Israeli production that visited London in the 90s to be thoroughly disabused of its reputation for triviality.

His political engagement became more visible over the years. He supported Havel’s Charter 77 in Prague, and was active on human rights issues with PEN, the international writers’ association. Every Good Boy and the superb television play Professional Foul (also 1977, dedicated to Havel), about human rights and football, were overtly political. In 1984, another television play, Squaring the Circle, celebrated the Polish Solidarity movement in a drama of politics and geometry.

Stoppard’s commitment as a citizen never clouded his dedication as a writer, and he baited his less rigorously intellectual critics with such pronouncements as “Personally, I would rather have written Winnie the Pooh than the collected works of Brecht,” or “Skill without imagination is craftsmanship; imagination without skill gives us modern art.”

Self-avowedly unable to easily think up plots, he relished opportunities of straightforward (and difficult) adaptation or translation, supplying texts for Pirandello’s Henry IV at the Donmar Warehouse in 2004, or a modern French three-hander (John Hurt, Ken Stott and Richard Griffiths), Heroes, set in a retirement home for war veterans in 2005, or for Chekhov’s Ivanov starring Kenneth Branagh at Wyndham’s in 2008. Best of all, perhaps, was his superb adaptation for the BBC of Ford Madox Ford’s tetralogy Parade’s End (2012) in five parts and starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Rebecca Hall. A final play for the National – where he served on the board between 1982 and 2003 – The Hard Problem (2006), was a look at sexual politics in a well-funded European brain science institution, and a comparative disappointment.

Stoppard directed his own movie of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead in 1990 and won an Oscar for best original screenplay for Shakespeare in Love (1999); his other screenplays included a co-writer’s credit on Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985), Empire of the Sun (1987) for Steven Spielberg, Enigma (2001) from the Robert Harris novel, uncredited script doctoring on Paul Greengrass’s The Bourne Ultimatum (2007) and an inventively theatrical Anna Karenina (2012) for Joe Wright.

He sealed a life-long liberating love affair with BBC radio drama with Darkside (2013), a surreal and engaging philosophical comedy, slightly weird, written to celebrate the 40th anniversary of Pink Floyd’s album Dark Side of the Moon.

A proactive president of the London Library, Stoppard was appointed CBE in 1978, knighted in 1997 and made a member of the Order of Merit in 2000.

He was twice divorced and is survived by his third wife, Sabrina Guinness, whom he married in 2014; by two sons, Oliver and Barnaby, from his first marriage, to Josie Ingle; and two sons, William and Edmund, from the second, to Miriam Moore-Robinson.

2 months ago

77

2 months ago

77