At the mouth of Lake Manchar, gentle lapping disturbs the silence. A small boat cuts through the water, propelled by a bamboo pole scraping the muddy bottom of the canal.

Bashir Ahmed manoeuvres his frail craft with agility. His slender boat is more than just a means of transport. It is the legacy of a people who live to the rhythm of water: the Mohana. They have lived for generations on the waters of Lake Manchar in Sindh province, a vast freshwater mirror covering nearly 250 sq km. The lake, once the largest in Pakistan, was long an oasis of life. Now, it is dying.

-

Bashir Ahmed in his boat on the lake, next to simple huts built on top of the right bank outfall drain

On the opposite shore, Bashir’s father, Mohamed, the head of this community of about 50 people, waits for him. The two men settle in the shade. “We were the lords of the lake,” Mohamed says. “This water was full of fish. Our boats were our homes. We thought they would never sink. But look now … the lake has turned to poison.”

That poison has flowed through a specific channel: the right bank outfall drain, or RBOD. Built in the 1990s, the canal was meant to make the salty soils of western Sindh fit for cultivation. In reality, it rerouted agricultural wastewater laden with fertilisers and pesticides, along with industrial effluent and sewage from several cities, directly into Lake Manchar. In just a few decades, the lake’s salinity has soared, oxygen has dropped, algae have proliferated, and the lake’s fragile ecosystem has collapsed. Climate breakdown has only hastened the disaster. A decrease in rainfall, combined with the construction of two upstream dams on the River Indus, has significantly reduced the flow of fresh water.

-

A Mohana hunter holds a thin branch with a living bird tethered to the end, which he uses as a decoy to trap wild birds

There was a time when Lake Manchar teemed with life. In the 1930s, more than 200 species of fish were recorded in its waters. By 1998, only 32 remained. Since then, about a dozen more have vanished. The Sindh Fisheries Department estimates that average catches have dropped from more than 3,000 tonnes in 1950 to 300 tonnes in 1994 and to less than 100 tonnes today. Many of the commercially viable species have disappeared, and what remains are often low-value fish, sold cheaply for chicken feed rather than human consumption.

While he now lives on dry land, Bashir was born on the water. He grew up on board a houseboat, part of a floating village that no longer exists. Twenty years ago, they were forced to leave and settle along the shores when fishing no longer brought in enough to maintain their boats.

“For us, leaving the lake was like asking the birds to stop flying,” says Ali Kasghar, who still captures birds on the lake. “The birds taught us so much. Like them, we lived on the water. Like them, we drank from the lake. And like them, we fed ourselves on the fish it gave.”

-

Children create a slide on the steep slope of the right bank outfall drain

-

The water by the drain is used for bathing, washing cooking utensils and doing laundry. In the 1930s more than 200 species of fish were recorded in the waters, by 1998, only 32 remained

Once, more than 20,000 Mohana lived in floating homes. Today, only about 40 such homes remain, housing fewer than 500 people. Their numbers continue to dwindle as the water grows more toxic.

Those who remain cling to their traditions – including the way they hunt birds.

-

Only about 40 floating homes such as these are still in use on the lake’s waters

-

Mohana children make rafts out of discarded polystyrene and use them to visit relatives or play together

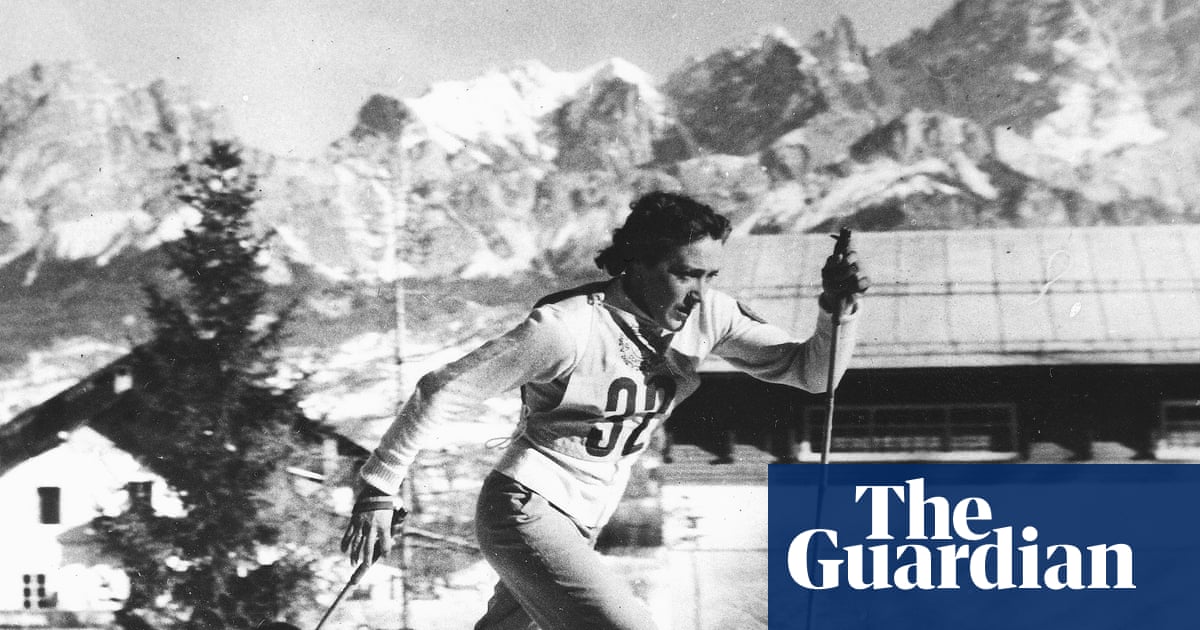

Kasghar is one of the last masters of this ancient technique. He glides slowly across the lake’s surface, led by a live bird tethered to the end of a slender branch. This feathered companion allows him to approach other birds without alarming them until the final moment, when he grabs them with lightning speed.

Others use an even more surprising method: submerged up to the neck, they fix a stuffed bird to their heads as camouflage. Fooled by the decoy, other birds come close.

The captured birds are sold at markets in nearby towns or used to feed the family. A few are kept and raised, becoming pets or hunting decoys in their turn.

-

Kasghar uses the lake’s birds to help him hunt

But the birds, too, are vanishing. Lake Manchar was once a key stopover on the Indus flyway, hosting tens of thousands of migratory visitors from Siberia and central Asia. According to the Sindh Wildlife Department’s 2024-25 waterfowl count, numbers across the province have fallen by more than half in just two years: migratory bird numbers plunged from 1.2 million in 2023 to 603,900 in 2024 and just 545,000 this year. Drought, shrinking wetlands and pollution are stripping away the habitats they rely on.

“It is partly thanks to the birds that we still survive here, around Manchar,” Kasghar says. “When they disappear for good, I fear we may disappear with them.”

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow the biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield in the Guardian app for more nature coverage

-

The number of birds stopping at Lake Manchar on their migratory journeys has halved in two years

2 months ago

66

2 months ago

66