When London’s Prince Charles Cinema has something to say, it declares it with large black lettering across its marquee. Once, during a summer heatwave, it beckoned punters with a blunt: SOD THE SUNSHINE COME SIT IN THE DARK. When its doors were boarded up during the first Covid lockdown it went for a rousing: WE’LL BE BACK. And after the coronation of King Charles: NO, WE ARE NOT CHANGING OUR NAME.

As is clear from the repertory of films on show – David Lynch classics in 35mm, all-night Japanese horror marathons, Sing-a-long-a-Sound of Music and screenings of The Room (frequently with a live Q&A from director Tommy Wiseau) – the cult Leicester Square spot (Quentin Tarantino’s favourite UK cinema) has a unique place in London’s West End. When the cinema found itself facing an existential crisis following a prolonged period of fraught negotiations with its new landlord, passersby only needed to look up to learn that the venue had a fight on its hands. Just three words were pinned to the board: SAVE THE PCC.

It was 28 January when the sign went up. The same day, the cinema launched a petition. It decried Zedwell LSQ, a subsidiary of Criterion Capital (one of the biggest property players in Leicester Square and Piccadilly Circus), for using its “significant financial resources to intimidate us”. Zedwell, the Prince Charles said, was demanding new terms that would make its future unsustainable: higher rent, a shorter lease and, crucially, a break clause that meant the cinema – which has been on the site since the 60s and operated under its current ownership since 1991 – could be forced to vacate with just six months’ notice.

Within 24 hours, the petition had collected more than 100,000 signatories and triggered a slew of coverage. GQ magazine gathered comments from Hollywood heroes including Paul Mescal, Robert Eggers and Christopher Nolan, the latter of whom simply said: “Film culture in Great Britain is unthinkable without the Prince Charles.” Danny Boyle told the magazine: “If this ‘ninth wonder of the world’ ever closes its doors, life will continue but London will die a little death.”

As the furore grew, attention shifted to the man behind Criterion Capital, a businessman named Asif Aziz. This wealthy property magnate – nicknamed “Mr West End” by newspapers after he bought the Trocadero in 2005 – was now thrust into the ring. In 2020, the Times asked if he was “Britain’s meanest landlord” in a story reporting on Criterion’s decision to take commercial tenants to court over unpaid rent during the pandemic. At the same time it was clashing with the Prince Charles, Criterion was ruffling feathers over its plans to buy the Central YMCA, a historic community gym and health club, which now seemed set to be developed into a Zedwell hotel.

But to many, what was happening to the Prince Charles Cinema and the YMCA was about something bigger than a negotiation over rent, or the financial viability of a health club. It was about the persistent threat of closure that so many cultural and community spaces in London face, the impact of rampant commercialism on the city’s cultural diversity, and the seemingly unchecked power that developers such as Aziz wield. It was a familiar fable, one that has played out many times before, albeit with different venues and different landlords. As Kate Mossman wrote in a piece for the New Statesman lamenting the “death of the West End”: “No city in the UK has developers with the same flagrant disregard for its own culture as London.”

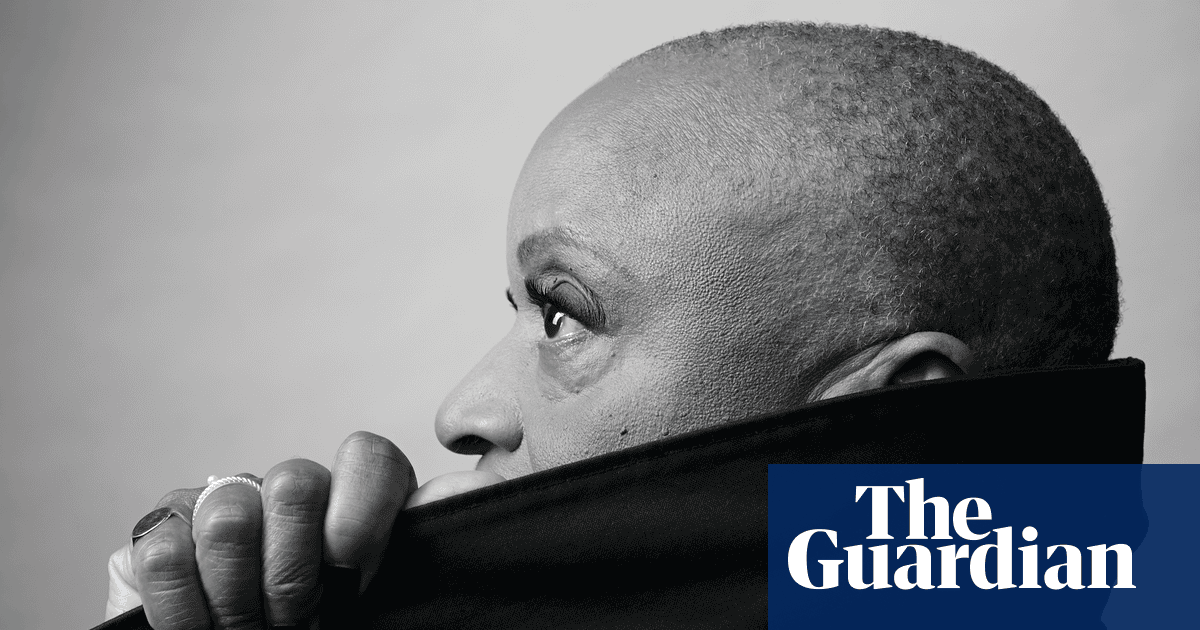

Throughout all this, Aziz remained silent – until now. I wanted to find out: who was this publicity-shy property magnate with the power to shape the heart of the capital? What was Mr West End’s vision for, well, the West End? Was he a uniquely hard-nosed operator? Or was focusing on one man a distraction from deeper, systemic issues relating to how urban space is negotiated in the UK? “Asif is very personable,” John Walker, a former director of planning at Westminster council, tells me. “But is often misunderstood.”

The first time Ben Freedman, the 64-year-old managing director of the Prince Charles, met Aziz, it was January 2023. Zedwell had just bought the freehold on the building from its previous owners, Soho Estates, and Aziz invited him to his office for a cup of tea. Freedman made the short walk to Babmaes Street, on the other side of Piccadilly Circus, where Criterion’s headquarters is tucked into the ground floor of a glassy modern office building. Inside, he was greeted by Aziz, 58, who is, in many ways, much like Freedman: charming, bespectacled, softly spoken, casually dressed. It was, as Freedman recalls, all very pleasant.

Freedman, who knew the cinema’s current lease was due to end in September 2025, was interested in Aziz’s plans for the building. “He said: ‘I don’t really know,’” says Freedman. Aziz asked Freedman if they’d like to stay, to which Freedman said yes. “Then he asked me to do a presentation for his board as to why they should keep us.”

Freedman put together a pitch deck, conscious that he was already on the back foot. “You’re a single operator dealing with a company that owns a big chunk of the West End,” he tells me, when we meet in the dimly lit foyer of the cinema in March. “You know … you’re a flea dealing with an elephant.” Still, he had some legal protection. The Prince Charles is covered by the Landlord and Tenant Act (1954), which entitles a tenant to a new lease at market rate unless the landlord intends to redevelop the entire building, or take it back for its own use. As long as Criterion wasn’t planning anything major, and they could agree to the terms of a new lease, everything should have been fine.

“We went back and forth,” says Freedman. “And he and I had a number of conversations about what rent we would be interested in paying.” At first, Aziz asked Freedman to make a proposal, then, “he said: ‘No, I need a figure beginning with this.’” Freedman made another proposal. “And he said: ‘No, I need more.’” Freedman became exasperated. “It was a conversation where you were bidding against yourself,” he says. By the end, the figure was nearly double the rent the Prince Charles was paying. The pair agreed it would be helpful to have an independent perspective, at which point Freedman commissioned two surveyor’s reports, which both independently stated that the existing rent was reasonable.

In October 2023, Freedman – who by now was aware that Criterion was pursuing planning permission to convert the office space above the cinema into a hotel – again met a representative of the company (and its surveyor). Freedman shared what he had been advised would be a fair rent, and Criterion responded that it still believed it was worth double. “They said: ‘We’re going to search the market,’” says Freedman.

A week later, Freedman had another meeting, this time with Aziz’s son, Omar, a director at Criterion. This encounter included some suggestions that Freedman found “bizarre”. The strangest was that they should sacrifice portions of the cinema. “‘Could you give up the circle, because we need it for access? Could you take away the front of the building so we can get wheelchair access to the hotel? Can you take a chunk of the auditorium so we can put a shop round the corner in Lisle Street, which we could rent out to somebody and that would mean that we would be able to afford your lower rent?’ It’s, you know, bonkers.” After that, things went cold.

Under the 1954 act, when there is a year left on a lease, a tenant formally requests a new contract and the landlord has two months to respond. So in September 2024, Freedman put forward a proposal for a 15-year lease at the rent they believed was fair and they “waited, waited, waited”. In January this year, Criterion came back demanding a higher rent, a five-year lease and a break clause that would entitle it to – as Freedman puts it – “kick them out” with six months’ notice should it gain planning permission for a redevelopment.

For Freedman, who had already been bracing himself for a legal battle, it was time for the nuclear option: going public. It was vital, he believed, to make it clear to Aziz that the Prince Charles was not simply your typical cinema.

A couple of days later, a local councillor offered to broker a new meeting between landlord and tenant. So Freedman returned to Criterion’s office to speak with Aziz. This time, the atmosphere was tense. “He expressed disappointment that I hadn’t picked up the phone to him and had chosen to go public with the issue. I said: ‘We hadn’t been able to talk to anybody for 18 months …’”

Yet progress, of sorts, was made. Aziz – informally, at least – agreed to drop the break clause, and said he’d be happy to agree to a 15-year lease. But he still wanted the rent increase, with an annual rent review. “And that’s in a market where rents are falling,” says Freedman. Criterion, Freedman says, has refused to provide any evidence that the higher rent it is proposing reflects the reality of the market.

Freedman is still awaiting a response from Criterion to their counter-offer. And with every month that passes, the possibility of the dispute going to court – in which a judge will determine what is a fair lease – draws closer.

London has always been under the thumb of powerful landlords, and they prefer to operate under the radar. Much of the city’s prime property is carved up between a handful of “Great Estates” that have held land there since Norman times: the Grosvenor Estate, the Cadogan Estate, the Gascoyne Estate. “Almost a thousand acres of central London remains in the hands of the aristocracy, church commissioners and crown estate,” writes Guy Shrubsole in Who Owns England?. “They own most of what is worth owning in central London.”

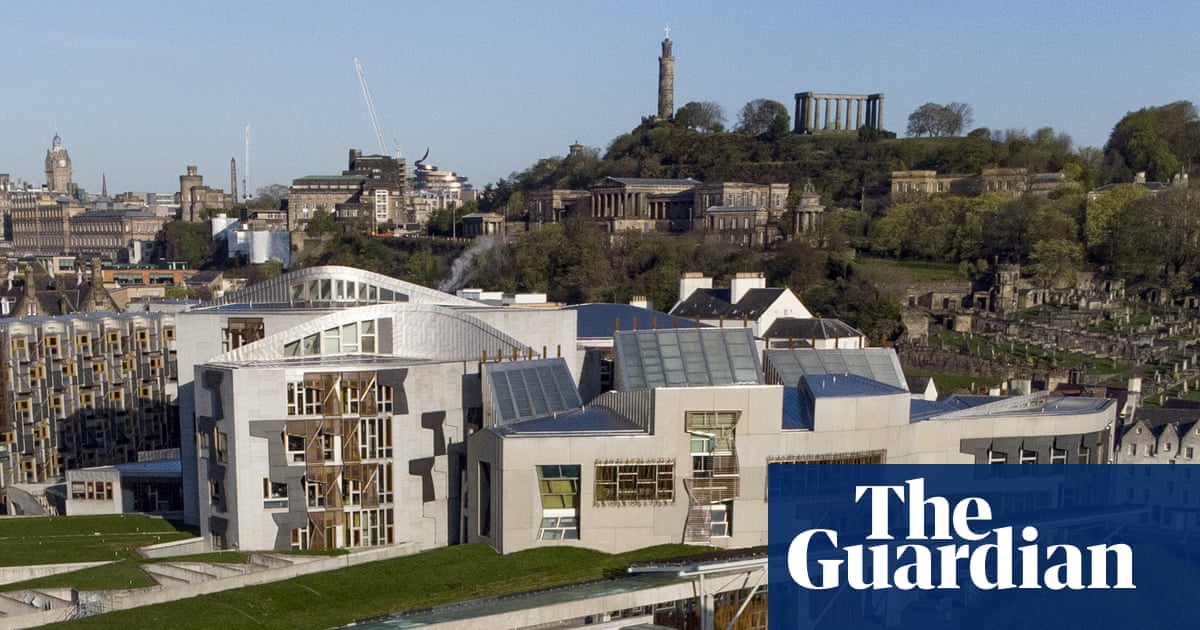

Other players are also family firms, including Soho Estates, which was founded in 1949 by the pornographer Paul Raymond and has a £1bn portfolio. Relatively speaking, Criterion is the new kid on the block. Its portfolio in central London is small when compared with the Great Estates and the crown, but if you stand in the centre of Leicester Square or Piccadilly Circus and look in almost any direction then you will see a building that it owns.

The aggregation of property into the hands of a small group has driven enormous change in the area. London’s major landlords are adept at driving up the value of their portfolio, rents included, often at the expense of the businesses that give a city its life. “More and more things are thought about simply through their financial value and less about their use value,” Mike Raco, a professor of urban governance at UCL, tells me. The consequence of this, in the simplest terms, is that the West End is being “hollowed out”.

Jonathan Glanz, a West End resident, former lord mayor of Westminster, and director of 45 West Group, a property management company, has seen the impact of this commercial homogenisation play out over 20 years. “It’s why, say, a chandelier repairer can no longer afford to be in Soho, why a startup business can’t be anywhere really in the West End,” he tells me. “Long-established family businesses have taken the view that their property is worth more than the businesses and have moved on.”

How to slow this process is an enduring conundrum. “It’s all very well to say we need a local bakery or local shops,” says Dr Patricia Canelas, a lecturer in sustainable urban development at the University of Oxford, “but how do we make that happen?” A strong planning system is part of it, she tells me, and it is vital that communities shout when they are unhappy, “but at the end of the day, property ownership rules the world”.

Fables about London and its developers are easily shoehorned into a David v Goliath narrative. Asif Aziz’s own story (I’m not the first to point out) more closely resembles that of Dick Whittington. Like Whittington, Aziz – who was born in Malawi in 1967 – arrived in the capital as a young boy with little to his name. While he has not risen to the rank of mayor of London, he is certainly close to the position; Aziz and Sadiq Khan can often be found rubbing shoulders at events in the capital. Today, Criterion Capital has a portfolio of prime real estate across London and the south-east worth about £6bn. Aziz now spends most of his time living in Abu Dhabi.

Aziz, so the story goes, was 16 when he grasped the first rung of the property ladder. He bought two shops in Deptford, converting the top-floor storage rooms into flats. London’s streets may have been paved with gold, but much of Aziz’s early wealth was accumulated doing business in Angola, where he ran a food and consumer goods distribution firm called Golfrate. After selling it for $20m in 2005, he returned to London to embark on a shopping spree for the capital’s biggest jewels. Among them were the Criterion Building (from which Criterion takes its name), the London Pavilion and the Trocadero, three grand buildings that surround Piccadilly Circus, the beating heart of London’s West End.

As Aziz’s property portfolio grew, so did his profile. Coverage of his business and personal affairs has not always been flattering. In 2011, the MP for Mitcham and Morden, Siobhain McDonagh, joined her constituents for a demonstration at Criterion’s office in Piccadilly. They were upset that Aziz had sat on a tower block in Colliers Wood for years, letting it fall into disrepair while the property accrued value. Speaking in parliament, she complained that the Trocadero had also been left collecting dust. “All we really want from Mr Aziz is for him to be a good neighbour,” she said. “Although if we are relying on people like him to behave decently of their own accord, we might have a very long wait.”

Aziz is “charming, well-dressed and very courteous”, one property adviser told the Times, “but he doesn’t give anyone a chance – he squeezes for the last penny.” Elsewhere, Criterion has been accused of buying and closing local pubs, and presiding over a poorly maintained and cockroach-infested housing block in Croydon. How much property Aziz really owns is hard to gauge. As Private Eye has reported, he can be linked to numerous Isle of Man companies that hold titles to UK properties.

But it hasn’t knocked him, or Criterion. “Asif’s glass is always more than half full; he is an eternal optimist,” Walker tells me. “I know some people have criticised Criterion Capital for buying and sitting on property, but that is not my perception … The reality is he has transformed some very difficult and challenging sites such as the Trocadero, which many others looked at and failed over many years. When he does things, he does them well.”

At the heart of Aziz’s portfolio is the Zedwell hotel brand, spearheaded by his daughter Halima, which opened its flagship branch in the Trocadero in 2020, bringing back into use a floundering building that was once a brash video-game arcade but had spent much of the past decade decomposing. Entirely windowless, the hotel pitches itself as a sanctuary for sleep in the heart of the city. Whether it is a masterclass in branding or a vision of dystopia, it is a hit. A constant stream of guests flow in and out of the large minimalist lobby, where they can check themselves in on tablets before taking a lift to their rooms. The basic doubles are about the same size as small rooms in most budget hotels, but the walls are blank and the bed cocooned within a floor-to-ceiling wooden frame – like a box within a box. And when you turn out the light, there’s nothing but darkness. In 2023, Criterion pushed the Zedwell concept one step further, opening the first underground hotel at Tottenham Court Road, next door to the Central YMCA (in the face of strong opposition from the local community). It plans to scale up to 8,500 rooms by 2028 – a number of them above the Prince Charles.

Mr West End may be the main character of this story, but he is by no means the only antagonist in the area. In March, it was reported that Veeraswamy, London’s oldest Indian restaurant, might have to close owing to a lease dispute with the crown estate – pitching a century-old Michelin-starred institution against King Charles himself. A petition has collected 14,000 signatures and the restaurant has applied to the courts to have its lease extended. It was also recently announced that Covent Garden’s Jubilee Gym is also going on the market due to financial challenges, contributing to the sense that only the most lucrative businesses and services can survive in this part of town. In a similar scenario to the Central YMCA, plans to sell it took place behind closed doors and without community involvement.

The property companies – which in recent decades have begun to work increasingly closely with local authorities to maintain and add value to the area – use a particular language to describe the changes they have brought about – one of “uplifting communities”, “maintaining vibrancy”, or “preserving architectural integrity”. It’s a language in which Criterion is fluent. “Community impact and social value guide every aspect of our portfolio,” it states on its website.

In a statement, it blamed the decline in the West End on a regulatory environment that has “grown less supportive of imaginative proposals aimed at revitalising the area” and pointed to its “long-term view” in the stewardship of its assets.

When Criterion talks about its socially minded endeavours, it cites the “revitalisation” of the Criterion restaurant (now home to a branch of the London chain Masala Zone), and its renovation of the Horses of Helios statue in Piccadilly Circus – a partnership with Westminster council and the crown estate that “not only preserves a significant piece of public art but also enhances the vibrancy of the West End”. It is also building a mosque and community space in the Trocadero.

Aziz has invested heavily in supporting Britain’s Muslim community and tackling Islamophobia. Much of this work is done by the Aziz Foundation, of which his daughter Rahima is a trustee. It also supports initiatives and events that celebrate Muslim culture in the heart of London, such as the Ramadan Lights, again close to Piccadilly Circus, which were switched on by Sadiq Khan in February.

after newsletter promotion

When I began reporting this story, it seemed unlikely that Aziz would agree to an interview. Then, one day, out of the blue, I received an email from Criterion’s head of communications. “I understand you have been inquiring about Mr Aziz,” she wrote. “We would like to invite you to one of his events, he will be attending and welcomes the opportunity to meet you.”

So I find myself at an open iftar sponsored by the Aziz Foundation and held in Trafalgar Square. It turns out to be an unostentatious affair – and free to attend, which gives it a gentle, unhurried air in an area in which it’s hard to blink without spending a tenner. Musicians play on a small stage, families wander around; a collective calm encircled by red buses, taxis and hordes of tourists.

I loiter in wait for Aziz; then, between phone calls, handshakes and waves to his familiars, Mr West End appears, slim and smiley in a simple blue jacket, jeans and trainers. He comes across as relaxed, unflappable. The Prince Charles situation, he assures me, with a shrug, is a lot of misinformation. Before, they were “paying nothing”, he says, and now have to pay market rent, so “it’s human nature to feel upset”. Anyway, in his view he’s always been a soft target for the media. “Is it Islamophobia …?” He leaves the question hanging in the air.

It’s a fleeting encounter, but one question seems to catch him off guard. I remind him of his various nicknames: “Mr West End … the Meanest Landlord. How would you like to be known?”

He smiles, purses his lips slightly and rocks on his heels. “No one has ever asked me that before,” he admits. I’m invited to drop by his office in a few days’ time.

Before I sit down with Aziz, I visit the home of Patrick Joy, 75, a former postman who was a long-term user of the Central YMCA. Like most of its 10,000 plus regulars, he only learned the fate of the club when an email was sent out informing him that it was no longer financially viable, and that it had been sold. As part of a wider campaign to save the centre, Joy volunteered to put his name down for a high court challenge, calling for an injunction to pause the sale to Criterion. The case was dismissed and the centre was closed on 7 February.

Joy lives in a rented flat off Gray’s Inn Road, the front room decorated by colourful ornaments and artwork, including an eye-catching Technicolor picture of a tiger. He sits in a wide leather armchair in a brown cardigan and slippers, and tells me how he used to deliver letters all over the West End at dawn and go dancing at the Hippodrome at night. “I’m a West End man,” he tells me.

As you’d expect from a postie, Joy has always been a morning person, and those were the sessions he attended at the YMCA. “It was more than just a gym … it was a community centre,” he says. “Especially for older people – a place where you can sit in the canteen and have a good chinwag.” He’s been embedded in the neighbourhood his whole life, but has watched it change in ways that don’t make sense to him. “It’s a case of big, big business taking over,” he says. “Big business just killing communities with no heart.”

After leaving his house, I wander into Soho, past the shuttered frontage of the YMCA on the ground floor of the brutalist St Giles building, to meet David Beida, a sage-like community organiser, part of the Save the Central YMCA campaign, and a member of the Soho Society, who lives on Dean Street. There, in a room full of cigarette smoke and De Chirico prints, he conveys his cynicism for Criterion; what he views as its disinterest in the equilibrium of the area. “If it had been any other major West End property company,” he says, “they probably would have sat down and talked to us when they started buying it.”

Camden council agreed to support the campaign (though admitted it had no power to stop the closure), and a meeting with representatives from Criterion was finally arranged. Andrew Shields, another campaigner who attended, says they hoped for a conversation about philanthropy, community and the role developers could play in preserving the West End. Instead, it resembled a business meeting in which the rent needed to occupy the building was floated, along with the possibility that the community could continue operating a portion of it.

The campaigners, however, are determined to retain the entire building for community use. They are now developing a feasibility plan, and waiting to hear whether the building will be listed. “Our anger is not necessarily with Criterion, they’re a business. They buy buildings,” says Shields. “Our anger is with the directors of Central YMCA, who took that decision to sell. But with Criterion, it requires dialogue, and [since that meeting] we’ve not had any.”

Shields tells me that all they want is to be listened to, for Criterion to “genuinely understand” that what’s been lost is more than just a building. The campaign continues to call on Criterion to live up to the community values it likes to boast of, but when it applied (successfully) to have the YMCA designated as an asset of community value, Criterion opposed it. In a recent social media post, the Save the YMCA campaign dubbed this the “duality of developers”.

This duality can result in some surreal community events. In December, Criterion held an occasion to raise money for the Soho parish school – the last of its kind in the area. Parents, children and “stakeholders” gathered at St Anne’s Church on Dean Street. There were drinks and speeches, and a group of school pupils sang Little Donkey and We Saw Three Ships. “It felt a little … strange,” one parent who attended tells me. “Very corporate … there wasn’t much integrating between the community and the corporate people.” She felt as though it was designed to let the public know that Criterion was doing something for the community, “but hearing about the YMCA and the Prince Charles, it kind of did feel a bit like you’re not doing as much as you actually could do”.

Later, I learn that one of Aziz’s daughters used to attend the school.

A few days after the iftar, two days after Eid al-Fitr, I arrive at Criterion’s headquarters. It’s an open plan space with a lively buzz. In the centre of the room, a number of architectural models are on show in glass boxes. Aziz greets me and I take a seat in his office, which is separated from the main room by a wall of glass. Inside hang contemporary oil paintings of Piccadilly Circus and family photographs. He hands me a copy of Muslims Don’t Matter by Sayeeda Warsi from a pile of about a dozen books on a coffee table and insists I read it.

“Property,” he says, leaning back in his chair, “is something tangible, something everyone sees.” From Aziz’s perspective, Criterion doesn’t behave any differently from the other estates in central London, “but here, it’s individually owned … there’s a person you can target. But I’m also targeted because I’m a champion of British Muslim issues. I’m very passionate about that. Very, very passionate.”

Aziz has always felt something of an outsider – ever since he arrived in London aged six, living in a flat in Balham with a coin-operated meter – and, like many immigrants, has been shaped by those struggles. “I come from a family which has lost wealth because of” – he takes a long, careful pause – “political or other events. So financial survival is very important.” The rags-to-riches narrative is enticing, but feels a bit simplistic. I am curious how a 16-year-old goes about buying a house. “At auction,” he tells me, dodging the question.

We talk about the Aziz Foundation, and I put it to Aziz that some people see a paradox in investing in a community with one hand, while seemingly disrupting local life with the other. “Our business interests are not at odds with our charitable interests,” he counters. He brings up the Soho parish school. “Twice it’s been through those threats of closing it down and we had a fundraising in December for that. Because it’s our community here.”

But the thing is, I say, the school used the YMCA swimming pool, and I know a number of parents there are upset that it’s closed. He seems frustrated by the suggestion. “I repeat for the fifth or sixth time, we did not acquire YMCA to close it down. Same with Prince Charles. We’ve not bought Prince Charles to close it down. We have a planning application to convert the upper parts into a hotel. Having the Prince Charles Cinema there adds value and panache to our building, to our hospitality offering.”

Aziz feels as if the Prince Charles row has become personal. His daughter Halima, who has dropped into the office and taken a seat beside us, points out that when the petition was kicking off, the words on the marquee were updated to read “Damn the Man”. “See,” he says, “they always have to individualise it.”

There’s an awkward silence. I’m unsure whether to mention that a billionaire property developer is as much “the man” as you could imagine, or point out that it’s a nod to the famous line from the 1995 film Empire Records, “Damn the Man, Save the Empire”, in which the staff of an indie record store fight to stop it being sold to a chain. Besides, a negotiation with a landlord is personal – it comes down to two people sitting down to cut a deal.

I suggest to Aziz that one of the frustrations felt in London is that “market rents” have been pushing out certain businesses, often resulting in independent businesses being replaced by chains – the homogenising, “hollowing out” that UCL’s Mike Raco raised, and that people such as YMCA regular Patrick Joy feel. Besides, according to Freedman, the “market rent” proposed by Criterion is being plucked out of thin air – it’s simply a rate Aziz believes he can demand. I guess, I say, many people feel that people like you have the power to make a choice …

“Of course we had a choice,” says Aziz. “We had a choice that we could have put in a planning application to demolish, put in a new cinema or a theatre and a far better building.”

Some weeks later, I check in with Freedman. The cinema has been ticking along; it is currently screening Joe Wright’s adaptation of Pride & Prejudice for its 20th anniversary and, in keeping with its idiosyncratic way of operating, they’ve had to call in a ghost hunter to investigate the source of a mystery flood that has been blighting the building. It turns out that the cinema is home to numerous ghosts, but none are responsible for water damage.

Repairs always need doing, but it’s difficult to know how to proceed while in limbo. Freedman is still waiting on a response from Criterion, and is upset to hear that Aziz continues to claim that this is a dispute about what the Prince Charles could pay, rather than what is fair. “We do not feel as though we are being treated as partners,” he says. “We feel as though we are being bullied.”

In a statement, Criterion said the claim it has used “significant financial resources to intimidate the Prince Charles” is “completely unfounded” and “reflects the Cinema’s negotiating approach to date”. It is, it says, seeking “market terms” and details such as a break clause are a matter for negotiation. “Both parties have engaged professional surveyors and representatives to advise them,” it added. “Should commercial terms not be agreed upon, the statutory process enables either party to apply to the courts to resolve the matter.”

There’s some good news, though. On 1 May, Westminster council approved the Prince Charles Cinema as an asset of community value, formally recognising what Freedman and thousands of others know to be true. “It raises the bar as far as planning permission is concerned,” says Freedman. “It is also recognition of the impact of the people who signed the petition and all the work we’ve done over the years. When you’re in a fight with someone who’s a lot bigger than you, then the more affirmation you can get the better.”

The Prince Charles Cinema has always been a defiant venue, and that’s the attribute it’s displaying now. In his battle against London property’s Goliath, Freedman refuses to be ground down, but it is not a fight he particularly wants to be having. “It’s a huge waste of resources,” he says. “We would rather be running a cinema.”

3 months ago

148

3 months ago

148