It looks more like the past than the future. A vast chasm scooped out of a scarred landscape, this is a Cornwall the summer holidaymakers don’t see: a former china clay pit near St Austell called Trelavour. I’m standing at the edge of the pit looking down with the man who says his plans for it will help the UK’s transition to renewable energy and bring back year-round jobs and prosperity to a part of the country that badly needs both. “And if I manage to make some money in the process, fantastic,” he says. “Though that is not what it’s about.”

We’ll return to him shortly. But first to the past, when this story begins, about 275-280m years ago. “There was a continental collision at the time,” Frances Wall, professor of applied mineralogy at the Camborne School of Mines at the University of Exeter, explained to me before my visit. This collision caused the bottom of the Earth’s crust to melt, with the molten material rising higher in the crust and forming granite. “There are lots of different types of granite that intrude at different times, more than 10m years or so,” she says. “The rock is made of minerals and, if you’ve got the right composition in the original material and the right conditions, then within those minerals there are some called mica. Some of those micas contain lithium.”

That’s what we are talking about here: lithium, the L-word. Or possibly the El Dorado word; lithium is often referred to as “white gold”, and in 2021 the then PM Boris Johnson declared that Cornwall would be the “Klondike of lithium”.

It is not breaking news that there is lithium here. Victorian miners reported finding it in the water coming from the ground. (You may know, possibly from Poldark, about Cornwall’s rich history mining tin and copper; it has been going on since the early bronze age, in about 2000BC.) Back then there was little use for lithium. Now it is a very different story. Its high electrochemical potential means lithium can hold a charge for longer than most other elements and so is ideal for use in rechargeable batteries. That’s phones, laptops and so much of the technology we use. Plus, electric cars and big battery storage projects. Lithium is now among the most important mined elements on the planet.

Most of the world’s lithium is extracted in Australia and the lithium triangle in South America (Chile, Argentina and Bolivia), as well as in China, which also processes and therefore controls a majority of it for use in batteries. Cornwall doesn’t compare in scale, but it is, says Wall, “probably the largest lithium deposit in Europe”. A couple of companies – British Lithium and Cornish Lithium – are leading the way to tap into it.

Jeremy Wrathall is the founder of the latter. When he graduated from Camborne School of Mines in 1988, mining in Cornwall was gasping its last breaths – with just four active mines left, down from more than 300 in the 1860s. Now there are none, though there are still some china clay (kaolin) operations. So Wrathall went to work in South African goldmines, before returning to London to work as a mining analyst and financier.

Cornwall remained in his heart, though, and when electric cars began to be a thing, he remembered hearing about the lithium there. “I put lithium plus Cornwall into Google and up came four historical records of lithium being found in water. I thought: that one is an awful long way away from that one, they must be geologically connected. And then I thought: maybe I’m on to something and should start picking up mineral rights. So that’s what I did.”

Along with the mineral rights for which he did deals, Wrathall acquired a number of 19th-century mining plans, which gave him information about geological features – the granite and what was in it. He founded Cornish Lithium in 2016.

Wrathall says the UK – particularly Cornwall – will be able to extract 50,000 tonnes of lithium (actually lithium hydroxide and lithium carbonate equivalent, depending on how it’s extracted) a year for more than 20 years – about 50% of the UK’s annual needs by 2030. There are two methods. One is to extract lithium from water via deep boreholes, which we will get to later. Here at Trelavour is the company’s “hard rock extraction” site. Wrathall picks up a small piece of rock. “You can see the sparkly bits, that’s the mica – all of this rock, everything you can see, has lithium.”

He explains that there will be some blasting, then the granite will be dug from the quarry and crushed before going on a conveyor belt to the processing plant in the valley. But, hang on; this doesn’t sound super sustainable, even if the intended destination is the UK’s transition to clean renewable energy. Lithium mining projects in Portugal and Serbia have been hampered by fierce opposition from locals and environmentalists. In Argentina, mining companies and politicians have been accused of robbing Indigenous people of their water and employing colonial-style divide-and-rule tactics in pursuit of the valuable metal. Why is that not happening here?

Wall explains that it is a very different process in South America, where brine gets pumped into a series of ponds and then evaporates slowly in the sun. Cornwall has neither the geology nor climate for that. Trelavour is a traditional quarry, “so you’ve got all your normal stuff associated with quarrying: drilling, blasting and lorries.” Environmental permits are very strict, she says, and they’ll need to sort out what they’re doing with the waste. “But the granite is pretty benign, it’s not like some of the sulphides, where you have a lot of trouble with acid mine drainage [the outflow of acidic water largely from metal and coal mines].”

Some of the byproducts could be valuable: silica for cement, sulphate of potash for fertiliser, gypsum for plasterboard. Wrathall says the company’s crushers are electric and it will look into using electric trucks. “We’re trying our best to go zero carbon, or very low carbon.” The situation in Cornwall is different from the controversial projects in Europe, he says, because the quarry already exists; they will simply be repurposing it. “You can see the damage is done. In Portugal, it is a pristine area, olive groves, it would be digging up people’s farms. This is not a farm. What are you going to do with this? It’s dangerous, fenced-off to stop people getting in. And at the end of it, we will rehabilitate it.”

I have found it hard to find anyone who is really against the project. Charmian Larke of the Cornwall Climate Action Network says: “Because the area is so destroyed anyway, the surrounding villages tend to be very poor, with poor health and educational outcomes.” Wrathall says the Cornish people are proud of their 4,000-year history of mining, “and it will bring back economic prosperity to an area with one of the highest levels of deprivation in the country”.

On cue, we are joined by Peter Morse, general manager of the hard-rock project here. He grew up in the nearby village of Roche. His family has been here for generations, he says, mostly working in the china clay industry, and he used to ride around in a truck with his grandad, driving in and out of the plants. He thought he would go into it, too, and did a geology degree. Instead, he went to the US, where he worked in the mining industry for 30 years.

Wrathall and Morse are what are known as “Cousin Jacks” – Cornish miners who went abroad to work. “If you go anywhere in the world and there’s a hole, there’ll be a Cousin Jack at the bottom of it,” says Morse. They took a bit of Cornwall with them: he says he could get a pasty on the shores of Lake Superior.

When he came back home, it was different from when he left: fewer people were employed in the china clay business. St Dennis, the village nearest to the site, used to have three pubs and a bunch of shops. Now there is just one of each. “And St Austell is not the town it was when I went to school there. It was bustling, lively – but it doesn’t feel like that now.”

Morse says lithium can help to reverse the trend. Cousin Jack is back. I also spoke to Noah Law, another local, now Labour MP for St Austell and Newquay. “Mining is part of our heritage, it’s part of what makes Cornwall great. It has made us wealthy in the past and can do the same again.”

Things have changed though. “Mining is more capital intensive than it used to be, and not as labour intensive. Part of the challenge is sharing the prosperity. I’ve levelled with the industry to say we’re really invested in this and are going to work hard to make a success of the industry, if it is willing to work really hard to make sure my constituents are sharing the spoils.”

Law says Cornwall can be a beautiful place and an industrial powerhouse, “because that’s what we have been for the most of the past 200-300 years. It’s only recently that Cornwall hasn’t been an industrial economy.”

Cornish Lithium employs just over 100 people, and the plan is to triple that. “Every mining job provides at least four times as many knock-on jobs,” says Wrathall. And not just another shop selling wetsuits or ice cream. “They’re good, but that’s not going to make any difference to the lives of people here. What is going to make a difference is the development of an industry that is already here, but is now seeing its next generation. It’s going to change Cornwall’s future.”

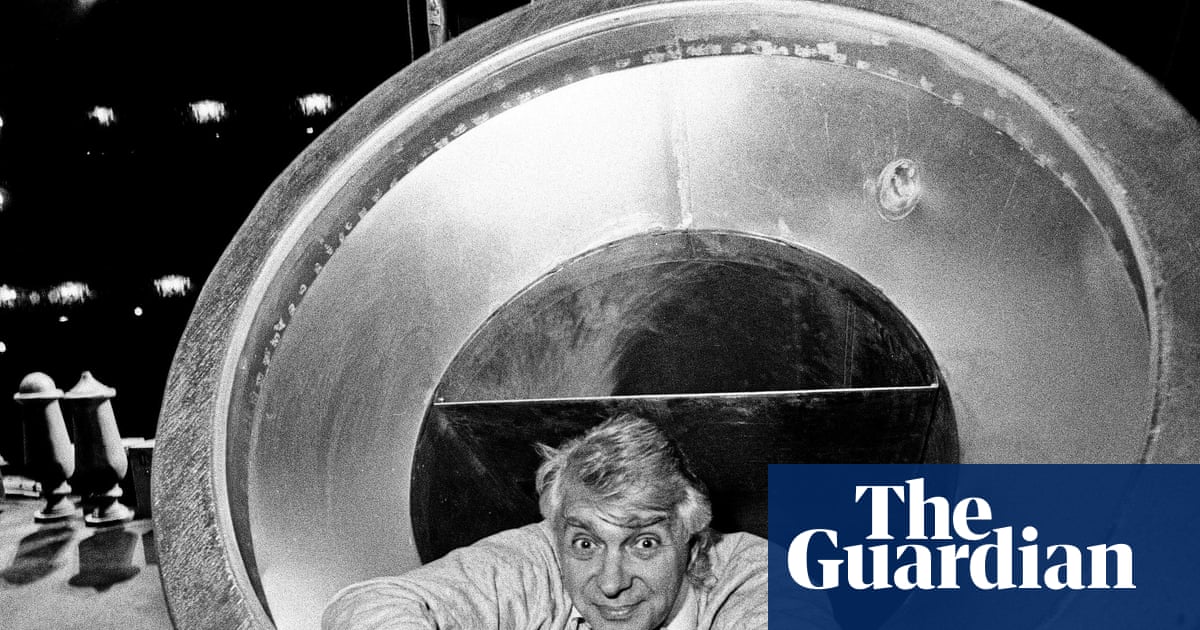

We have come down from the quarry to the processing plant, where the lithium gets extracted from the granite. At this stage it’s a demonstration facility, but it still takes up a huge shed, a remnant of a former china clay facility. The crushed granite comes in at one end and the lithium is extracted in a series of processes. First physical – milling, soaking, spinning – followed by chemical separation that involves dissolving the mica in sulphuric acid. All the machinery – mills and pipes, scrubbers and chillers, pumps and vats – looks rather Willy Wonka. And here’s a bag of the end product – lithium hydroxide, a white crystalline power that looks, frankly, illegal.

About 20 miles away, the villages of St Day and Gwennap were once big centres for tin and copper mining and the surrounding landscape is dotted with derelict brick engine houses from that time. Between the two is now the centre for Cornish Lithium’s other project: geothermal extraction. It doesn’t look much, a capped borehole in the corner of the United Downs industrial estate, but under the cap a shaft goes down 800 metres. This was the first exploratory hole. They’ve since done others, including one 2km deep on a farm a few miles away at Cross Lanes. The results were very positive and Cross Lanes has recently been granted planning permission for the country’s first commercial geothermal lithium production facility.

In another shed, Adam Matthews, who leads the geology team, shows me what it’s all about. Laid out on trays are hundreds of core samples of rock from the Cross Lanes drill holes: they look like pencil leads for giants. One is solid, “siltstone and sandstones mostly, the darker bands are muds, nothing of much interest”, says Matthews. But here’s one from 1,700 metres down, “and you can see fractures running throughout the rock. The water flows naturally throughout those fractures.”

In this water – hot brine – they have found lithium. The next stage is to drill two new larger diameter 2km-deep holes, one to pump the water out, the other to return it once the lithium has been extracted. It’s probably the least impactful, most sustainable way of getting hold of lithium.

The water at that depth is between 80 and 90C and Wrathall says it could be used to provide low-carbon heat energy for communities and industries. There are few houses to heat near to Cross Lanes, but he says the heat could be used in agriculture. “There is an opportunity to build greenhouses there, to grow tomatoes and cucumbers.”

It sounds wonderful – pumping water out of the ground, extracting the mineral that will help the country on its transition to renewable energy, then returning the water to where it came from … with a byproduct of locally grown salad.

But we’re not quite there yet. The next phase will be to build a demonstration plant to produce samples of lithium. If successful, the company will build a commercial production plant there. The Trelavour hard rock site is also still at the demonstration phase. Wrathall thinks they will first be producing lithium commercially in 2028 or 29. Even then the UK will still have to import about half of what it needs. Reliance on China isn’t over yet.

Since they’ve been looking at lithium in Cornwall, “we’ve seen critical minerals go from ‘Who cares?’ to ‘Oh my goodness, what are we going to do?’” says Wrathall. “Why is Trump interested in Greenland? Minerals. Ukraine? Minerals. Canada? Minerals? I’m just hoping he doesn’t find out about Cornwall!”

2 hours ago

3

2 hours ago

3