When Jade and her family first arrived at the detention facility in Karnes county, Texas, she wasn’t really sure what to think.

“I guess I was confused and scared,” said the 13-year-old. Her parents were doing their best to reassure her that everything would be OK, but she knew they were in danger of being deported.

She and her parents were one of the first to be sent to Karnes – one of two detention centers the Trump administration has commissioned to hold immigrant families. At first, she was the only kid – as far as she could tell – in the sprawling beige structure. Immigration officials had confiscated her family’s belongings, including her phone and her Nintendo Switch.

There were a few books and games at the detention center, and a playground – but little else to distract her from her worries. “I just didn’t know what would happen to us,” she said.

The Texas-based legal non-profit Raices said it was aware of at least 100 families held at Karnes since early March, after the Trump administration restarted the practice known as “family detention” – locking up children along with their parents. Those detained include families who had recently crossed into the US, as well as those swept up in cities across the country. Among the youngest detainees was a one-year-old child.

Jade and her parents, Jason and Gabriela, are among the first to speak out about the conditions inside Karnes since being released. Now, back home in Mississippi, Jade said she’s still trying to make sense of what happened. “I don’t know how to explain it. It was weird,” she said. “I still feel confused and scared.”

The Biden administration suspended family detention in 2021 amid growing reports of sexual harassment and violence, medical neglect and inadequate food. The Trump administration has not only reinstated the practice, but Trump’s border czar, Tom Homan, has said the administration would seek to challenge a longstanding settlement that limits the amount of time children can be held in detention.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) assistant secretary Tricia McLaughlin said that “adults with children are housed in facilities that adequately provide for their safety, security, and medical needs”.

But human rights groups and pediatricians have said that these facilities – which are operated by private prison companies – are inherently harmful. In a letter to the Trump administration, several leading healthcare and pediatric groups, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, emphasized that “detention itself poses a threat to child health” and “even short periods of detention can cause psychological trauma and long-term mental health risks”.

“Children experience time differently than adults do, and even brief periods of detention can have long term devastating consequences on a child’s development,” said Elora Mukherjee, director of the Immigrants’ Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School. “It’s cruel.”

‘I wanted to cry the whole time’

Jade and her family had fled a surge of violence in Colombia in 2022, and had managed to make a good life for themselves in Mississippi.

But things changed this year as the Trump administration ramped up its immigration crackdown. Jade was afraid to go to school, worried that immigration agents could come find her there, or take her parents while she was away. Jason and Gabriela had trouble finding work – employers had become squeamish about hiring workers without a legal status.

“It was a very, very tough situation – it had become impossible to continue living here,” Jason told the Guardian in Spanish.

So they decided to leave. Jade packed up her most prized possessions, including her Nintendo and all her favorite clothes. “I was like, I’m excited,” she said. “I’m going to Canada. I’m going to make new friends.”

But they never made it to Canada.

At first, they encountered Canadian border agents and tried to explain they were seeking asylum. But those agents told them they’d be ineligible, and turned them over to US border officials. “That’s when everything got out of hand,” Jason said.

Agents handcuffed him and Gabriela, and drove them to Plattsburgh, New York and then Buffalo. “I wanted to cry the whole time,” Gabriela said.

“Our daughter had never seen us like that – handcuffed like prisoners,” Jason added.

In Buffalo, they were released from the cuffs, and sent via commercial flight to Texas. “The whole time we are trying to reassure our daughter, ‘Amor, nothing is wrong, it’s OK,’” Gabriela said. “But we didn’t have anything to distract her with, because she didn’t even have her Nintendo, her cellphone, she didn’t have her tablet, she couldn’t listen to music.”

By the time they entered the detention center – a sprawling concrete facility set against the dusty landscape of Karnes county, Texas – they were exhausted. “We were in a state of shock,” Gabriela told the Guardian. “Maximum shock – because we didn’t know what would happen to us.”

Jade was too young to remember the violence her family had left behind in Colombia, but Jason and Gabriela’s minds constantly flashed back to the threats and extortion they had faced. “It was anguish on a daily basis,” she said.

During their first few days in detention, they didn’t know who to call for help. “How else do we fight for ourselves? We have nothing here,” Jason said. “Each day like this was torture.”

Officials had confiscated all their things, and the family was given second-hand clothes and towels to use. They were able to buy minutes to make phone calls, but it was expensive.

Gabriela and Jason struggled to find the words to help their daughter. “Imagine seeing your child sad because they can’t go to school. And you can’t even say, ‘Let’s go to the corner. Let’s go get ice cream. Or some chips,’” Gabriela said. “How do you explain any of this to a child? Your mom can’t do anything for you, your dad can’t do anything.”

“She’s entering adolescence and everything that happens to her now will mark her. Everything that has happened could have broken her in some form, traumatized her,” she added. “That’s what distresses me as a mother.”

Eventually a few other families arrived at the facility, including siblings aged three, six and eight. The youngest ones didn’t understand what was happening, so they weren’t as scared as she was – but they were just as tired, Jade said.

She liked when the radio played at the detention center, especially when the Weeknd came on. “That’s my favorite singer,” she said. “I just tried to sit on the grass and listen, and look at the sky.”

Relief finally came when they were able to connect with lawyers from Raices, who have been working with several families held at the detention center. Jade, Jason and Gabriela were finally released on 25 March – after about three weeks in detention – and their lawyers are now helping them seek legal status to remain in the US.

All the families that were at Karnes have since been transferred to a bigger detention facility in Dilley, Texas – which is more remote.

“The bottom line is that these individuals have final deportation orders from federal judges,” said McLaughlin of the DHS. “This administration is not going to ignore the rule of law.”

Raices said that assertion is “objectively untrue”.

Immigration judges are not the same as federal judges. And as a result of Donald Trump’s asylum ban at the southern border, “many families have not even appeared in front of immigration judges”, said Faisal Al-Juburi of Raices.

At the same time, the administration ended several legal service and education initiatives for immigrants – narrowing opportunities for families inside the center to connect with lawyers, Al-Juburi said.

The immigrant rights organization also contests the DHS’s assertion that Dilley has been adequately retrofitted for children.

The facility, which is run by the private prison company CoreCivic, is not a licensed childcare facility and thus a violation of the protections afforded children under the Flores Settlement Agreement, a decades-old consent decree that requires the government to hold children in the least restrictive setting and release them as quickly as possible.

How family detentions began, ended, and began again

The Trump administration isn’t the first to detain families.

For decades, Democratic and Republican administrations have held immigrant families in specialized facilities – and the practice has elicited widespread criticism from pediatricians and mental health experts, and lawsuits from human rights groups.

The family detention system took its lasting shape in 2001, and particularly post-9/11. The Bush administration had wanted to ramp up immigrant detention, and promoted family detention as an alternative to separating families and sending children to shelters while their parents were detained.

Reports of human rights abuses in these facilities quickly followed. Families with children were held in prison-like conditions, with limited privacy and access to the outdoors. There was inadequate food and medical care, and reports of sexual abuse by guards.

But family detention didn’t stop. Even as advocates sued the government and campaigned to close some family facilities, the government built others.

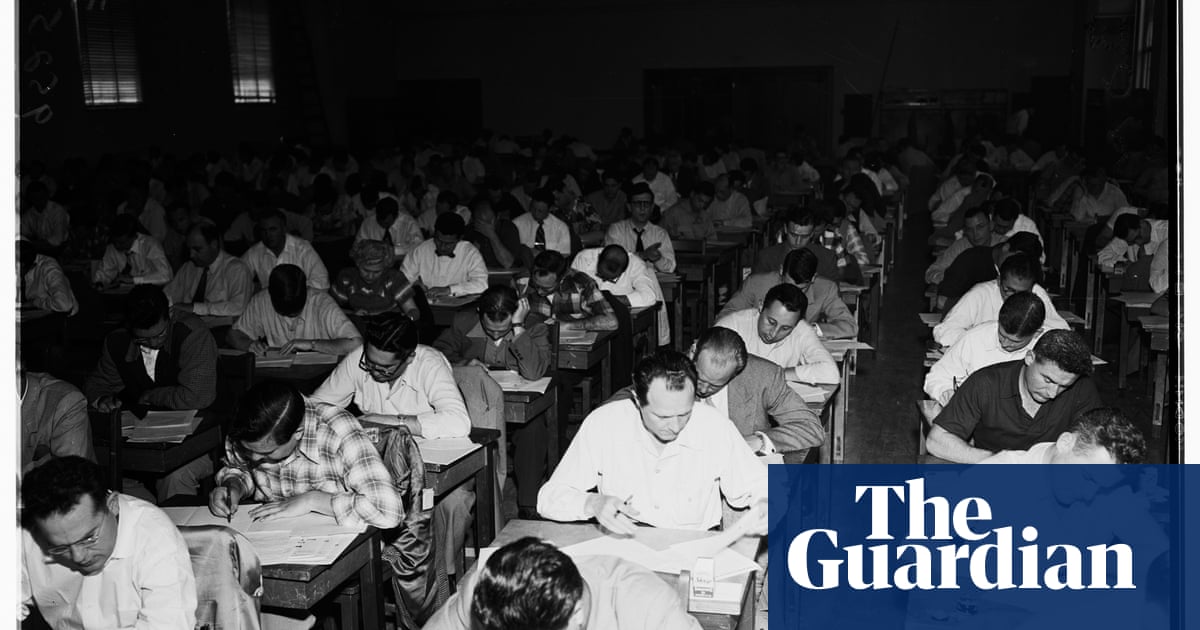

In 2014, as families and unaccompanied children began increasingly arriving at the US southern border, the Obama administration contracted with private prison companies to open the Karnes and Dilley facilities, and the US family detention program grew to its largest since the internment of Japanese Americans in the 1940s.

Legal challenges to the practice continued. In 2015 a judge ordered the release of children with their mothers, but then the first Trump administration pushed, unsuccessfully, to indefinitely detain families.

In 2018, a 21-month old toddler who became sick while being held at the Dilley detention center died of her symptoms shortly after being released.

Though the Biden administration stopped detaining families in 2021 – opting instead to track immigrant families via electronic monitoring and regular check-in appointments – it left in place most of the infrastructure to restart the practice.

And earlier this year, the Trump administration did just that.

Karnes, which the Biden administration used to hold adults, was recommissioned to hold families. Dilley, which had closed in 2024, reopened last month.

Karnes, operated by the private contractor Geo Group, is more like a traditional adult prison, retrofitted with play sets, said Javier Hidalgo, the legal director at Raices. Cinderblock walls are painted with murals of zoo animals. Families are allowed to be together during the day, but at night, mothers and children sleep together while fathers sleep in separate dorms.

The South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, meanwhile, is more akin to an “internment camp”, said Hidalgo. Before it was a detention center, it was a migrant labor camp. But in the end, both centers are, “essentially, jails”, he said.

In past years, the centers were commonly used to hold families newly arriving at the southern border. Officials kept families detained while evaluating their eligibility for asylum, and released them into the US if they passed an initial screening.

But the Trump administration has suspended asylum requests at the border, and unauthorized crossings have dropped precipitously. Many of the families in detention now have been apprehended by Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (Ice) officials in cities and towns across the US. Some were picked up at traffic stops, and others were arrested despite complying with orders to check in regularly with Ice.

“Some of the families in detention have been here for a long time,” said Hidalgo. And it’s unclear how long the administration will be willing to detain these parents and children, including those with pending legal proceedings that could take months to resolve, he said. “Keeping them detained seems like it’s for the purpose of punishing families, and deterring them.”

At least one other family held at Karnes – asylum seekers from Venezuela including a six-year-old and an eight-year-old – had also been arrested at the Canadian border, while trying to leave, according to Raices. Others included the nationals of various countries, including Brazil, Romania, Iran, Angola, Russia, Armenia and Turkey.

“I’ve been working on issues of family detention for years,” said Mukherjee, who has litigated on behalf of children and families who have faced medical neglect and abuse at various facilities. “And I can’t believe we’re doing the same thing again, almost 20 years later. Reopening of family detention centers exemplifies the cruelty that is animating the Trump administration’s immigration policies.”

Back in Mississippi

Now that she is back in Mississippi, Jade said she feels calmer, she said.“But I haven’t told most of my friends that I’m back, and I can’t take it any more,” she said. “I just told one friend, a good friend, and he said he wouldn’t tell anyone else.”

She doesn’t know how to explain to them what happened to her family, or how uncertain their lives still are. It’s not like she knows how much longer they’ll get to stay in Mississippi.

It could take months or longer for lawyers to work out their immigration case. In the meantime, they remain afraid of being swept up in the administration’s immigration crackdown once again.

So they’ve been lying low, at home. It’s a bit barren, because the family had either sold or packed up most of their things before heading to Canada. But they are glad to be able to wear their own, freshly laundered clothes, Gabriela said.

Jason was wearing a shirt printed with stars and stripes. When Jade pointed out to her dad that it also had the words “Land of the free” (“Tierra de los libres” she translated) – printed across the left side, the whole family began laughing.

He’d actually bought it to wear for the Fourth of July. “Actually we have lots of shirts like this – we’re quite patriotic,” Gabriela said. They have baseball caps with flags, and red, white and blue outfits for the whole family. “We just fell in love with this country. We love the security, the people. It’s a beautiful places where we live, in Mississippi. We are actually very much in love with this place.”

They never wanted to leave. “It is tough, but I have told my wife and daughter that we have to live now, because life may end tomorrow,” said Jason. “Here we have known freedom. Here we get to prolong life a little bit longer.”

The Guardian is not using Jason, Gabriela and Jade’s full names in this piece to protect their privacy and safety.

2 hours ago

4

2 hours ago

4