Norway has never looked as wet as in the photographs of the late Tom Sandberg. There are shots of drizzle and puddles, of asphalt slick with mizzle. A ripple of water appears to have a hole in it, a figure looms behind a rain-dappled window, a gutter glows after a downpour.

Shot in either bold chiaroscuro or gentle orchestrations of greys, these are pictures with the power to make the everyday seem dreamlike. But they are also uplifting, in a confusing kind of way, like being told to dress for sun even when the clouds are black.

Sandberg, as a new retrospective at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter next to the Oslo fjord makes clear, was not only Norway’s most famous photographer, pivotal in making the medium a serious art form in the Nordic region during the 1980s and 1990s. He was also a paradoxical character: hard-living, erratic, with a propensity for fanning his own myth with his tongue firmly in his cheek – and yet able to produce compositions that are contemplative, calming and uplifting.

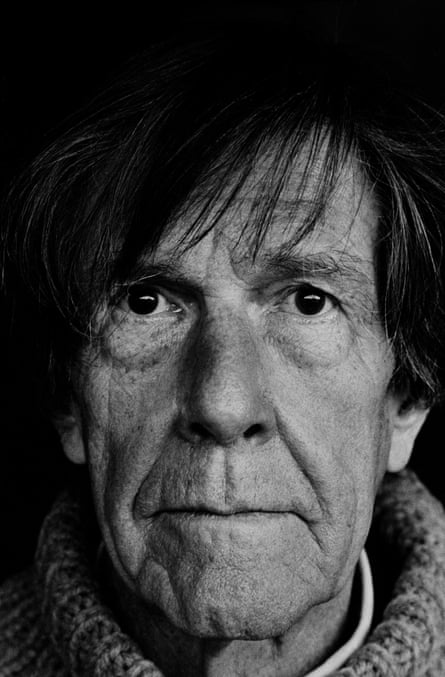

Covering four decades, from student work taken in the mid-1970s through to pictures made shortly before his death in 2014, Tom Sandberg: Vibrant World is the first major Sandberg show since his death aged 60. The setting is apt: Sandberg was once the in-house photographer at Henie Onstad, capturing art happenings in its galleries and making closely cropped, vastly enlarged, monochrome portraits of visiting dignitaries, including the composer John Cage and the artist Christo. They are topographical in their scrutiny of pitted, sandpapery skin.

He was born in 1953 in the town of Narvik on the coast of northern Norway. The family subsequently moved to Oslo, where Tom’s father worked as a photojournalist. “His father took him to the darkroom for the first time and exposed Tom’s hand on the photo paper. He said he was immediately smitten by that alchemical magic and never looked back,” recalls the art historian Torunn Liven, a long-time friend and trustee of the Tom Sandberg Foundation.

After his father abandoned the family, Sandberg helped his mother raise his sister in a rough suburb of the city. In the mid 1970s, he studied photography at what is now Nottingham Trent University, where he was taught by the American photographer Minor White.

Sandberg considered the darkroom process, in which he experimented with materials and retouching, to be a pivotal part of image-making. And, as his practice progressed, his prints became larger, almost cinematic. A noirish interior of the lounge at Oslo’s Gardermoen airport could be a film still from a Wim Wenders feature.

He returned to Oslo in the late 1970s, and began collaborating with printers and designers. Though he developed an interest in Zen-like compositions, his social life was far from monk-like.

“Tom had a huge social capacity. When he went in a taxi, he’d make friends with the taxi driver. He was friends with Norway’s crown princess,” says Liven. “He had a large need and capacity for having people around him. I think that unrest is the shadow side of that liveliness. And that, in a sense, his work arrested that unrest.”

Liven recalls how Sandberg had a particular affinity with young photographers who sought to learn his “wizard darkroom skills” and careful editing process, an old-school meticulous, intuitive and slow way of working. “We are very happy at the foundation that all the 15-year-olds from the secondary schools in the county around the museum area will participate in a workshop inspired by the Henie Onstad exhibition,” says Liven. “The teenagers will be restricted to work on one single picture, instead of the usual overload of endless digital snapshots.”

Morten Andenæs, Sandberg’s former assistant, photographer and co-curator (with Susanne Østby Sæther) of the Henie Onstad exhibition, recalls his unruly moments as well as his productivity. “He was a wild soul,” he says. “He was one of those guys with a wry smile. He didn’t take himself seriously but he took his work very seriously. It was how he dealt with existential issues.” Sandberg struggled with alcohol and substance abuse, says Andenæs. “He would periodically go on benders.”

Sandberg told Andenæs that “if it weren’t for photography he’d probably go to the hounds.” Rumours swirled around him. “If you look at his ear in portraits, part of it is missing. And how did that happen? I think he loved myth-making. Like, was it a woman who bit off his ear? That kind of stuff,” says Andenæs. “He would tell interviewers that he dreamt in black and white.”

Although Sandberg’s obsessive methodology, poetic sensibility and pared-back subject matter suggests a modernist lone wolf – his photographs often feature solitary figures with their back turned to the camera – he was no recluse. “He was seen by everyone he drew into his orbit,” notes Andenæs. “And he had a drive and intuition that rumbled on like a lorry without brakes.”

His human subjects are really studies of strange shapes. In one, a man appears to dance with his own shadow. In the early 2000s, he photographed his young daughter, Marie, as a whirligig of blonde hair. He shot human doodles.

“I don’t think he was one thing. He was a diverse person,” Marie, who is now 30 and has been at the helm of her father’s estate for more than a decade, tells me. “He was a very funny person and charismatic. But not always easy to be with.”

How was he as a father? “He was always very protective of me when I was a child. We had many different chapters as well. And I chose to live with him when he didn’t have the best time of his life,” Marie says. She sees the photographs he took of her as a form of self-portraiture. “I think he saw a lot of himself in me.”

Marie recalls how her father would take his camera bag with him everywhere. “To go from our house to the tram it could take anything from 10 minutes to two hours. He was taking pictures of me, the street, the sky, the ground. He just saw moments he wanted to capture.” That engagement with his subjects and surroundings extended to his friendships, as Morten Andenæs recalls: “Being in his company felt like the sun was shining on you.”

There were some periods of sharpness and sobriety. In his lifetime, he saw considerable success, including a solo show at MoMA Ps1 in New York in 2007, and his legacy continues to grow. Henie Onstad has Sandberg works on loan from the Norwegian National Museum and the Tangen Collection, arguably the most important collection of Nordic photography in the world.

The exhibition includes just one photograph of the man himself: a self-portrait taken in 2001, in which Sandberg is seen sitting in an armchair in an empty room. He looks like a security guard. The man you wouldn’t notice.

2 months ago

55

2 months ago

55