In 2003, the Stanford social scientist BJ Fogg published an extraordinarily prescient book. Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do predicted a future in which a student “sits in a college library and removes an electronic device from her purse”. It serves as her “mobile phone, information portal, entertainment platform, and personal organiser. She takes this device almost everywhere and feels lost without it.”

Such devices, Fogg argued, would be “persuasive technology systems … the device can suggest, encourage, and reward.” Those rewards could have a powerful effect on our relationship with these devices, akin to gamblers pumping quarters into slot machines.

Four years later, Apple launched the first iPhone. At Stanford University, Fogg taught Behavior Design Boot Camps that Wired magazine called “a toll booth for entrepreneurs and product designers on their way to Facebook and Google”. There, Fogg proved his theory to be spectacularly true: portable computers really could be used to “change what we think and do”.

As it turns out, one of the main ways they do so is by compelling us to spend hours and hours in front of them. Today, anxiety around screen time is ubiquitous throughout the generations. Ofcom found nearly a quarter of UK five- to seven-year-olds have their own phone, with 38% using social media. But it’s just as likely the oldies among us will be spending hours on ours. I was shocked to find my daily average was over four hours: mostly before and after sleeping, spent on news websites and YouTube.

There is huge debate in academia as to the effect smartphones, and their social media apps, are having on us. While psychologists such as Jonathan Haidt and Jean Twenge argue that they make children more anxious, fragile and depressed, and amplify political polarisation, others, including Pete Etchells and Amy Orben, believe the evidence for this is thin.

I am inclined to think the effect of Apple’s brilliant invention, plus Fogg’s dark genius, has been profound. My use of these machines has been compulsive: when I walk my dogs having left my phone at home, I find myself repeatedly grabbing for an empty coat pocket, my arm moving independently of free will. I read fewer books because of social media; I concentrate less in front of films and TV shows. I watch YouTube more than the BBC, ITV or Channel 4. I have been through phases of forcing myself on to a virtually app-less dumb phone, but the convenience and often necessity of maps, parking apps and train tickets pushed me back.

Yet my smartphone has affected my life in often negative ways. The world I disappear to inside it has made me – and probably you – angrier. That’s my main impression of how the world has changed since 2007: we’re all a lot more pissed off with each other. And I really do blame phones. Humans are profoundly social and wired to solve the problems of existence by forming into collaborative groups. When we feel we belong and are valued, we’re happy; when we feel isolated and worthless, we become anxious and depressed.

Smartphones have gamified and monetised these powerful aspects of human nature. They don’t benignly offer us the connection and status we desire: they strategically withdraw it in order to drive engagement. Whenever we’re outraged by the behaviour of an identity group that’s not our own, it’s an attack on our status: we are drawn further into our phones to find out more and perhaps take part in a counterattack – an attempt to restore our threatened status and reinforce the connection with our team. We’re made to feel good or bad by likes, reposts, comments or follower-counts, but our phone issues these precious rewards unpredictably, just as a slot machine does – and just as Fogg described. It’s this unpredictability that helps make them compulsive.

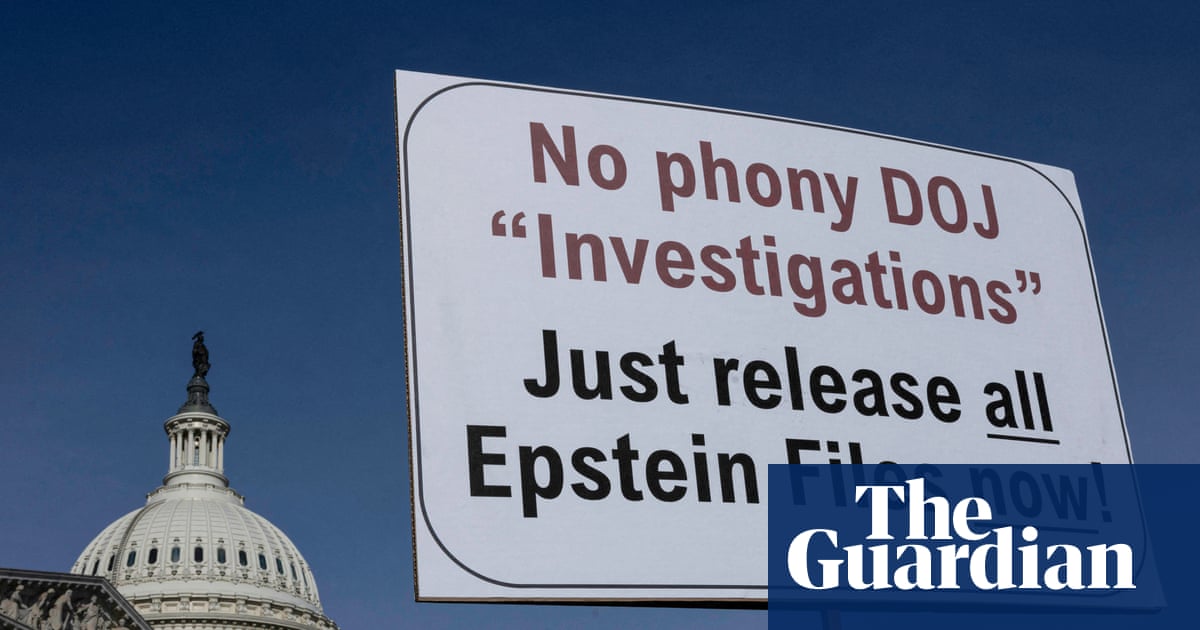

For us deeply social animals, much of our social life now takes place inside apps designed to manipulate via the manufacturing of social competition and tribal conflict. Of course we’re tired and angry and suspicious of each other. But at least we have a greater awareness of this now. More than 60 Labour MPs have recently urged the prime minister to follow the example of Australia where under-16s have been prohibited from using social media sites.

My own social media habit has been mostly vanquished by dint of the sites becoming dreadful. Instagram – where I used to post photos and enjoy those of friends and colleagues – now forces me to watch endless short videos by annoying people I have no interest in. Facebook is mostly absent of news from friends and family, and is instead a stinking river of dreadful memes and inane arguments. What was Twitter – a useful tool for promoting my work – has been superseded by X and Bluesky, both useless for this and petri dishes for the worst of human behaviour.

I do worry, however, about what is coming. The heavy-handed way in which large language models (LLMs), such as ChatGPT, flatter egos to give users a sense of status is currently a bit of a joke. But LLMs are new, and will rapidly improve. Human psychology is eminently hackable – as dogs have learned over tens of thousands of years, and romance scammers have figured out in 20. As BJ Fogg predicted, “suggest, encourage, and reward” and we will be yours. The device Sam Altman and Jony Ive are rumoured to be making, in which a wearable AI buddy will accompany us all day, learning about us and helping us and telling us we’re great, has the potential to burrow into our minds and become a relationship that feels essential and profound – the ultimate example of a technology that can “change what we think and do”.

1 hour ago

5

1 hour ago

5