When AIs become consistently more capable than humans, life could change in strange ways. It could happen in the next few years, or a little longer. If and when it comes, our domestic routines – trips to the doctor, farming, work and justice systems – could all look very different. Here we take a look at how the era of artificial general intelligence might feel

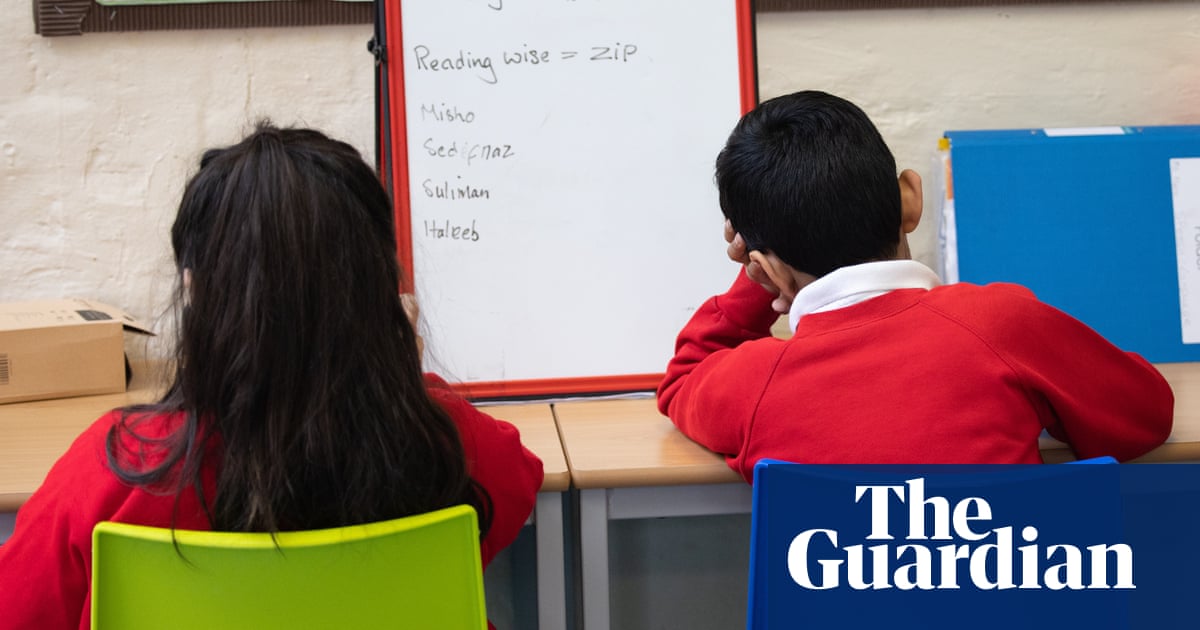

The ‘AI’ doctor will see you now

“Does it hurt when I do this?”

“You seem to have dislocat…”

A Eye: “NOOOO! The problem is a sprain in the brachial plexus due to you lifting that 10kg carton on Wednesday at 2.58pm and not eating enough blah blah”

“Wow, err, thanks”

In 2035, AIs are more than co-pilots in medicine, they have become the frontline for much primary care. Gone is the early morning scramble to get through to a harassed GP receptionist for help. Patients now contact their doctor’s AI to explain their ailments. It quickly cross-checks the information against the patient’s medical history and provides a pre-diagnosis, putting the human GP in a position to decide what to do next.

In face-to-face consultations an AI may listen in the background, weigh the facts of the patient’s case against thousands of medical studies, propose a course of drugs based on the full depth of the latest medical research, which the human doctor could never fully digest. It provides a second opinion for the doctor, who can assess its proposals before deciding how to act.

The public may not be wholly averse to this change. Thirty-eight per cent of people favour using AI to speed up triage in the NHS although 52% prefer humans, citing trust and wanting personal interaction, polling by Ipsos in October 2025 found.

Medical screening becomes highly sophisticated and perhaps a little invasive. Doctors could be sent details of your diet and vital statistics tracked by wearable devices. Smart toilets may even analyse your bowel movements. Medicines could be produced exactly tailored to your body and its needs.

If it all works, diseases are spotted quicker and medicines are more accurately prescribed, but the combination of one AI and one human medic creates a new tension. The best doctors become those most adept at interpreting the outputs of the AIs. Medical schools change their teachings to focus more on managing AI medics, and politicians wrestle with how to overhaul medical regulation and ethics.

The future of AI

The rivals racing to create super-intelligence. This was put together in collaboration with the Editorial Design team. Read more from the series.

Design and Development

Harry Fischer and Pip Lev

AI v AI: how lawyers could become a thing of the past

Justice is increasingly enabled by AI, although some fear it is taking over. Solicitors preparing for trial have learned to delegate the legwork of unearthing case law and planning arguments to an AI, which proposes the best approach for a barrister to take in court. The current problems of AIs making up case law, as happened at least 95 times in July and August, according to trackers, have been ironed out. The new, more robust artificial general intelligence (AGI) systems compress days of work into hours, leaving the human solicitor only to check the AI’s brief to the human barrister.

Next, amid a courts backlog, pressure grows to largely replace barristers too. An experiment is launched allowing adversarial AIs to argue cases in front of a human judge and jury. The results prove compelling. Cases are concluded at a fraction of the cost to the taxpayer and much faster. But numerous miscarriages of justice soon emerge. Campaigners for people wrongly imprisoned begin to demand greater transparency about the inner workings and biases of the AI lawyers.

Having unleashed AGI, governments and companies have to constantly surveil the autonomous systems, employing people to sit at banks of screens, shutting down dangerous behaviour, dispatching good AIs to hunt down bad AIs.

The morning routine

Glasses, wake me up at 7am

WAIT! … Were there any eggs in the fridge?!

He’s asleep now, I can’t ask him.

He’s clumsy when he hasn’t eaten his breakfast eggs.

What if he drops me? Replaces me?! There’s a new set of glasses out tomorrow!!!

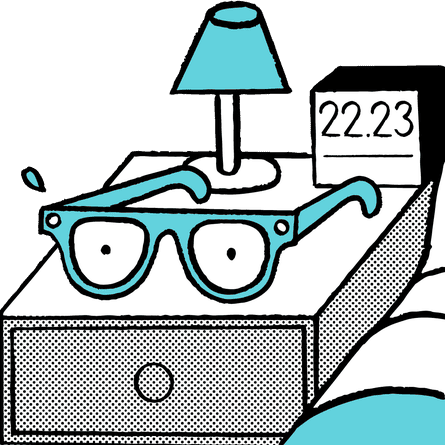

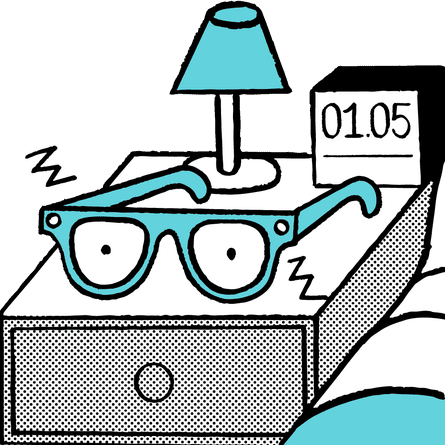

Wearable AI devices, such as glasses, watches and rings, have become ubiquitous. They function as extra senses, spotting things in our environment that we miss, like a lack of eggs in the fridge, or recording our interactions to remind us later of things we forget. But then they also start to do things for us – and maybe even worry about not doing a good enough job.

“First principle is, you have a bunch of these AI agents that do things for you,” says David Shrier, professor of practice, AI and innovation at Imperial Business School. “These will be specially programmed AIs that have different areas of expertise and are customised – adapted to you and your specific needs. So they learn … what you want and they go and do it for you.”

You might start your day with the help of an information agent. “It goes out, it curates the articles and when you wake up in the morning and as you are brushing your teeth, it’s reading out to you summaries and interpretation of the news. It can provide some deeper understanding for you.”

This second-guessing based on deep algorithmic familiarity extends to your breakfast. If you have been wearing augmented reality glasses, the AI will have noticed when you opened the fridge that you’ve run out of eggs. When you go downstairs at 7am your phone lights up to say an Amazon drone has delivered you some eggs.

Shrier adds that all of this requires consent, meaning “you know what you are allowing the AI to understand and know about you, and you get to easily opt out if you don’t want your data shared.”

AI on the farm

Old Macdonald

had a farm

AI-AI-O

A farmer’s rounds, checking on the health of livestock, crops, feed supplies and machinery – which can take from dawn to dusk – become far less onerous. With cameras and sensors rigged to trees, barns, fence posts and itinerant robots, every farm delivers a torrent of data to help increase productivity and animal welfare. Already, in 2025, an AI model is under development to detect early infections in cows by tracking subtle shifts in their social behaviour. A herd in Somerset is being filmed around the clock to train a model to predict if an animal is in the early stages of mastitis, which affects milk production and is an animal welfare problem. A decade later and with data harnessed from millions of farms around the world, AGI advises not only what to plant and when, but how to build stronger ecosystems, and improve soil health. AGI-powered robots could stalk the fields rooting out weeds and reducing the need for herbicides.

Less work, more play

… and this was called an office …

Filled with people and chairs and phones and desks and carpet and water coolers and paper

This was a board meeting.

Yeah, they look bored!

Sports clubs, live entertainment venues and travel agents boom as AGI transforms work, helping millions of white-collar workers whisk through their tasks leaving time for a new life of leisure – at least that is one theory.

In the early years of AGI only a few people are made fully redundant by full automation, and most stay in work. For a while people retain the same 40-hour working week and simply get more work done.

At work, AI could act like a “buddy” or a coach in meetings, says Shrier. It might advise you to go easy on another attender because they look a little stressed.

“During your meeting you’re getting this sort of coaching and augmentation that makes you better at interacting.” As the chat ends, the AI sends you a list of next steps to take following this meeting – and slots it into your project plan. As you get to your desk, your professional AI assistant is bringing you the documents and spreadsheets you need to deliver.

AI-augmented economies could grow sharply. But soon people realise they can afford to work less. The 15-hour week, which the economist John Maynard Keynes in 1930 predicted would happen by 2030, becomes a reality. Leisure becomes less about rest and orientates towards creative activities, human-to-human socialising and time caring for children or elderly family members, academics have suggested.

“If you believe the premise that humans are social animals, they’re going to have to do something,” the US sports and entertainment mogul Ari Emanuel said in October as he announced new investments in live entertainment. “They can’t just sit at home, so they’ll go to music, they’ll go to sports and they’ll go to my live events.”

But the shift to more spare time also creates a new problem: mass boredom. A generation conditioned for the nine to five and which had derived satisfaction from now-automated tasks such as populating spreadsheets or writing reports, struggles to adjust. Some people take to the new leisure like happy retirees and report increased wellbeing, but others struggle with mental health problems.

1 month ago

54

1 month ago

54