For one of Victorian literature’s most distinctive voices, who was once hailed as a genius by Oscar Wilde, very little has been known about Amy Levy for more than a century.

But audiences will now have the opportunity to become more deeply acquainted with a writer whose pioneering work explored women’s independence, Jewish identity and same-sex desire.

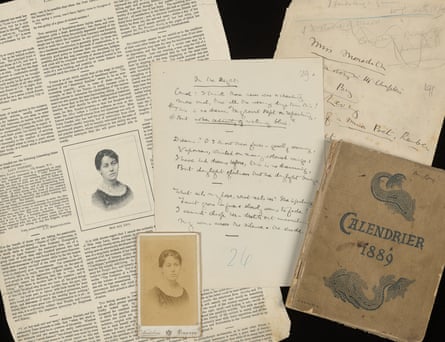

The University of Cambridge has announced it has acquired and for the first time unsealed Levy’s personal archive, including letters, draft manuscripts, photographs and diary entries. It is expected the material will inform a wealth of new scholarship on her life, work and mental health.

“It’s rare nowadays for a coherent corpus of a 19th-century author’s papers to come to light,” said John Wells, senior archivist at the Cambridge University Library. “We were determined to take the opportunity to make her archive available in the place where she studied and where she visited even in the last months of her life.”

Levy was born in 1861 into a middle-class Jewish family in London and entered Newnham College in 1879, becoming only the second Jewish woman among Cambridge’s first generation of female students.

She wrote three poetry collections, three novels – including Reuben Sachs and The Romance of a Shop – numerous essays and a series of articles for the Jewish Chronicle. When she died by suicide in 1889, aged 27, she was recognised by her contemporaries as an exceptional talent, with Wilde writing her obituary and commending the “sincerity, directness, and melancholy” of her work.

The newly available collection – which until now was owned by a private corporation – offers a vivid portrait of the intellectual and social circles that shaped Levy’s writing, from the early feminist New Woman movement to the cultural debates surrounding race science, art and identity in Victorian-era Britain.

Linda K Hughes, professor emerita of English and the Addie Levy professor of literature at Texas Christian University, who is working on a book project about Levy, said she believed the documents would not only transform academic study but also be of interest to a wider public.

“I read Amy’s poetry decades ago and they have haunted me ever since,” Hughes said. “Not only was she a fine and evocative writer, but she was also so complex. She affirmed her Jewish identity, but she was also an atheist. She seemed to get along very well with men, but she was a queer woman.”

Hughes said Levy had built a social network at Newnham and also in her later years, especially through Vernon Lee (the pen name of Violet Paget) “who was well connected to everybody including Wilde. Levy entered Lee’s circle, in fact she fell in love with her, a love that unfortunately was never returned.

“When Wilde received a one-page manuscript from Levy for his magazine the Woman’s World, he was bowled over by the story and called Levy a girl of genius.”

Researchers believe Levy’s work speaks directly to contemporary conversations around feminism, LGBTQ+ literature and Jewish identity and say she foreshadowed debate that would come long after her death.

“She was ahead of her time, which was perhaps one of the reasons she never entirely found her niche,” Hughes said. “She struggled with queer identity and how she fit into a heteronormative society. Marriage was not an option for her, but neither was having a career like a school teacher, which she abandoned to become a writer full-time.

“She has long been interesting to people who study Jewish women and their history. And today, when we have in the wake of the global pandemic so many young people struggling with depression, anxiety, troubled psyches, even suicidality, understanding her might be of interest and solace to a wider public too,” Hughes said.

The collection includes Levy’s 1889 appointment diary, in which increasingly sparse entries trace the last months before her death from inhaling carbon monoxide. A final, moving entry, written the day before she died, said: “Alone at home all day.” But Hughes said Levy in many ways had “a rich, full, exciting existence” too.

“She could be humorous at times, which shows in her writings. She did suffer from a trifecta of challenges, including neuralgia. She was growing increasingly deaf, which leads to social alienation and isolation. And she also suffered from depression.

“Though she never quite found happiness, it was always something she insisted on: the right to be happy, even ecstatic.”

1 month ago

53

1 month ago

53