If a TV programme sets about sequencing the genome of Adolf Hitler – the person in modern history who comes closest to a universally agreed-upon personification of evil – there are at the very least two questions you want the producers to ask themselves. First: is it possible? And second, the Jurassic Park question: just because scientists can, should they?

Channel 4’s two-part documentary Hitler’s DNA: Blueprint of a Dictator is not the first time the self-consciously edgy British broadcaster has gone there. In 2014’s Dead Famous DNA, it inadvertently answered both these questions in the negative. Having first cast aside ethical integrity by paying Holocaust denier David Irving £3,000 for a lock of hair purporting to belong to Adolf Hitler, the programme’s makers then discovered it not to be Hitler’s and thus useless for DNA sequencing.

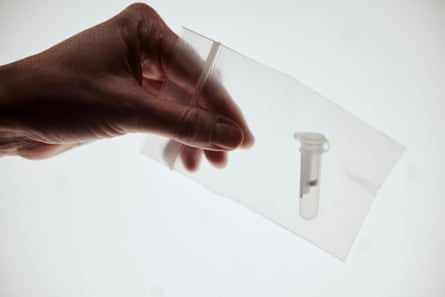

Airing just over 10 years later, the producers of this new programme at least made sure to answer the “is it possible” bit. Inside an obscure military history museum in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, they managed to track down a blood-drenched swatch of fabric cut by a US soldier from the sofa on which Hitler killed himself. In their attempt to authenticate the blood, they failed to get a fresh DNA sample from any of Hitler’s surviving relatives in Austria and the US, who are all understandably reluctant about media exposure.

But a Hitler male-line relative’s swab collected 10 years earlier (by a Belgian journalist investigating a rumour that the German dictator had fathered an illegitimate son during the first world war) yielded a perfect Y-chromosome match. Whether they got the relative’s permission to use his DNA for this purpose is unclear. Still, they knew they had Hitler’s blood, and could squeeze it for genetic information.

In Professor Turi King, they managed to sign up the scientist whose DNA verification of the Leicester car park remains of Richard III set the gold standard for doing genetics on TV in a way that is both accessible and responsible. Teamed up with Dr Alex Kay, a credible historian of the Nazi era at the University of Potsdam, they extracted a raft of insights about Hitler’s ancestry, biology and mental health. Should they have?

Some of the insights are scientifically sound and will contribute to historical debate. For one, the programme finally puts to bed an old rumour that Hitler had Jewish ancestry. Its source is the fact that Hitler’s father Alois was an illegitimate child and the identity of his paternal grandfather was unknown. It was only ever speculation, but the fact that it was repeated by Russia’s foreign minister Sergei Lavrov as recently as 2022 shows how persistent such rumours can be.

The researchers also found robust evidence – the deletion of a letter from a gene called PROK2 – that Hitler had some form of a well-known but rare genetic disorder known as Kallmann syndrome, which prevents a person from starting or fully completing puberty. This chimes with medical records from Landsberg prison, where Hitler was held after the failed Munich beer hall putsch in 1923, unearthed by German researchers in 2010. In them, an examining doctor certified Hitler with a “right-side cryptorchidism” – not quite the missing ball of the British second world war song, but an undescended right testicle. Up to 10% of people with Kallmann syndrome also have a “micropenis”; more prevalent symptoms are low or fluctuating testosterone levels.

The programme insinuates that what justifies it peeking into Hitler’s pants is that he “was so keen to hide” something, such as by asking for his body to be burned after his death. This is an odd argument: historians mostly agree that this came upon hearing news of Mussolini’s dead body being paraded in public – rather than a fear that Channel 4 will one day measure his member.

But there is a better argument to be made: that these medical conditions can help our understanding of Hitler’s psychology. Did he transform a sense of personal deficit, perhaps influenced by fluctuating testosterone levels, into an ideological cause? Did the Nazi führer have an inability to establish sexual connections that he compensated by marrying himself to the Fatherland?

If Hitler’s DNA: Blueprint of a Dictator had stopped here, it may have made a solid programme: sensational but also credible. Instead, the makers also set out to “assess [Hitler’s] genetic propensity for psychiatric and neurodevelopmental conditions”, by carrying out polygenic risk score (PRS) tests. From the results, they assert that Hitler had “higher-than-likely average likelihood of ADHD”, a “high probability” of some autistic behaviours, a “propensity for antisocial behaviour” and “a high probability of developing schizophrenia”.

PRS tests are part of a booming industry that promise to estimate individuals’ risks for developing not just diseases but also behaviours: popular websites such as ancestry.co.uk, where people can submit swabs to trace their heritage, now also automatically suggest to subscribers whether they are likely to have certain “traits”, such as “trying new things”.

Many scientists fear this to be part of an insidious creep towards genetic determinism that is not backed by evidence. “Polygenic risk scores tell you something about population at large, not about individuals,” says David Curtis, an honorary professor at the UCL Genetics Institute. “If a test shows you to be in the upper percentile of polygenic risk, the actual risk of acquiring a condition may still be very low, even for conditions that are strongly influenced by genetic factors”. A psychological test may determine whether you have a “propensity” for schizophrenia – a PRS test, many scientists say, cannot indicate a propensity in the same sense of the word.

When it comes to autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, the risks of stigmatising these conditions by attaching them to a universally reviled figure are especially glaring. If the takeaway from watching Hitler’s DNA for some is that “Hitler had autism”, will those with these neurodiversities be branded Little Hitlers? Or, conversely, does it garner sympathy for the prime architect of the Holocaust and the second world war?

The programme does acknowledge these risks. “Going from biology to behaviour is a big jump,” says British psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen in the first episode. “There’s a big risk of stigma.” But voicing caveats is undermined if you just go on speculating anyway.

“One of the things that we as geneticists are really, really trying to get across is that genetic determinism is wrong,” Turi King tells me in an interview. “We cannot say for certain that Hitler had any of these conditions, only that he was in the highest percentile in terms of genetic load for some conditions.”

It’s a word of warning that the film’s editors have not fully taken to heart. When a psychiatric geneticist from Aarhus University presents Hitler’s polygenic risk score for ADHD in the programme, it is shown to be merely “higher than average”, yet in the voiceover a few seconds later, this becomes a “propensity for ADHD”. Within two minutes talking head Michael Fitzgerald, who specialises in diagnosing historical figures with autism, says: “People with ADHD, like Hitler”. When I raise the ADHD claims with King, she seems to express surprise that so much has been made of the findings for the condition in the final cut, since they were only “moderately elevated”.

King’s findings have been submitted as a scientific paper to a reputable medical journal. Production company Blink Films say they couldn’t have held back airing the film until the paper has passed peer review as the pace of such academic procedures can be glacial. Given that the programme has been seven years in the making, and that the claims made in the documentary are nothing short of history-shaping, that decision is still surprising.

At the very heart of the Nazis’ so-called “race science” was the idea that our blood is where our destiny lies. In Mein Kampf, Hitler claims that purity of the blood is what enables individuals to make “correct” decisions and bonds a nation together, and its contamination through racial mixing is what causes individuals to act “incoherently” and leads civilisations to their doom. The most troubling thing about Hitler’s DNA: Blueprint of a Dictator is that those involved in making it may have read these passages carefully then continued to make the programme in the way they did anyway.

1 month ago

45

1 month ago

45