Nestled between the US state of Washington and Vancouver Island, the San Juan Islands are a vibrant haven for North American wildlife. Here, all of the world’s remaining 74 southern resident sub-species of orcas find sanctuary, surfacing daily from the depths of the Salish Sea.

Out at sea watching the whales is Dr Deborah Giles, an orca scientist, with her colleague, Eba. Eba is a brown and white rescue dog with a remarkable nose. Found as a cold, wet, five-month-old puppy on the streets of Sacramento, she has been detecting whale scat – or faeces – since the age of four.

Dressed in a bright orange lifejacket – and sometimes goggles – Eba perches atop Giles’s research boat, scanning the wind. When she catches a whiff of orca faeces, she raises her nose, sometimes whimpering or wagging her tail to point Giles in the right direction. Orca-detecting dogs have become an unlikely ally in the fight to save the whales.

“We wanted to use Eba because it allows us to stay really far away from the whales and not stress them out,” says Giles, a member of the marine conservation organisation SeaDoc Society.

Through the study of whale faeces, researchers can uncover a wealth of biological insights from a single sample, including diet, hormone levels, exposure to toxins, pregnancy, gut microbiome composition and the amount of microplastics in their system, as well as the presence of parasites, bacteria and fungi.

Eba wears a collar adorned with a small strip of lime green and black neoprene to work. It was once part of a toy belonging to Tokitae, or Toki, a southern resident orca taken in a mass capture in 1970. She spent 53 years in captivity at the Miami Seaquarium before dying in 2023, just months before a planned return to her native waters.

Also known as Lolita, and named Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut by the Lummi Nation tribe, her story became a rallying cry for orca conservation. When she died, her longtime trainer gifted the strip of wetsuit to Giles – a quiet tribute to a whale who should have come home.

Once Eba locks on to a scent trail, Giles scoops the floating faeces and processes it in a small wet lab at the boat’s stern. A centrifuge separates faecal matter from seawater and the sample is sent for lab analysis.

Data from these samples has revealed key insights into the challenges facing the southern resident orcas.

Where there was once a thriving population of the whales in these waters, the group now faces mounting threats. A sharp decline in Chinook salmon – their primary food source – combined with increasing toxicants and disruptive vessel noise, have pushed them to the brink of extinction.

Unlike the mammal-eating sub-species Bigg’s killer whale, which number about 350, and the northern residents, with more than 300, southern residents are the smallest orca ecotype in the eastern Pacific Ocean.

They are genetically and culturally distinct from other populations, and like the northern residents feed exclusively on fish. Once plentiful, their population has declined nearly 20% since the late 1990s.

This is particularly concerning to those who treasure them the most. Across the islands, the whales are celebrated. Images of their black and white bodies grace shop windows, T-shirts and cafe walls. But their presence runs deeper. For many Indigenous communities, including the Swinomish tribe, the whales are considered kin.

“We consider the orcas, or blackfish, part of the whole web that connects us as a tribe to all living things,” says Steve Edwards, chair of Washington state’s Swinomish Indian Tribal Community.

Alex Ramel, a Washington state representative and whale advocate, agrees. “They are just part of the culture and the community. Every time we read about one of the southern residents being washed up or a baby being born and not making it, it’s a topic of conversation in our community.”

In January, one grieving mother made headlines when seen carrying her dead newborn. It was her second loss since 2018, when she famously pushed her deceased calf for more than 1,000 miles. Earlier this month, another southern resident was spotted pushing her dead calf around with its umbilical cord still attached.

For Giles, who has studied the whales for two decades, their plight is symptomatic of deeper ecological damage. “They’re an ecosystem indicator,” she says. “Everything that’s causing their decline is our fault so it’s our responsibility to help them recover.”

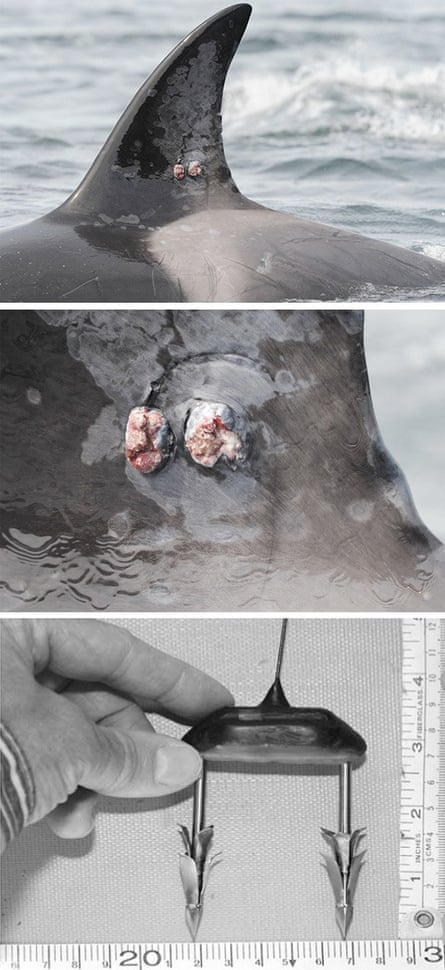

Whale monitoring used to involve invasive techniques such as firing barbed biopsy darts and satellite tags into the animals’ dorsal fins. In 2016, one such effort ended in tragedy when a whale died five weeks after tagging, probably due to a fungal infection introduced at the wound site.

Even less harmful methods, like using telescoping poles to collect breath samples, can be disruptive. “Having a boat at 30ft is very close. That would most likely elicit a stress response,” says Giles. “If it’s constant, they have this elevated stress level.”

Now, scent-detection dogs like Eba, coupled with new technologies, are expanding the toolkit for non-invasive conservation practices.

Out on the boat with Giles are James Sheppard, a scientist at the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, and Charlie Welch, an SDZWA volunteer and head of Proper Voltage, a company focused on sustainable battery technology. Together, they have spent a decade developing conservation drones that can capture samples of the cloud-like plumes of breath from orcas’ blowholes with mounts holding petri dishes.

Sheppard says: “We need to get data that is robust and as close to real-time as possible, so that we can find out if there’s a real problem. Then the animal-care staff can go in and stage an intervention if it’s needed.”

Out on the Salish Sea, a pod of seven Bigg’s killer whales soon appear – the southern residents are elsewhere. The team seizes the opportunity. With practised ease, the drone glides several feet above the whales.

Once a whale surfaces, the drone’s petri dishes collect mist from its blowhole, capturing genetic material, reproductive hormones and signs of disease.

“We get a snapshot of what’s happening inside the animal,” Sheppard says, adding they are also finessing radiometric thermal sensors that use infrared radiation to measure internal body temperature.

The duo’s drone operations have maintained a perfect flight record with no collisions, and operate under strict federal guidelines to minimise disturbance.

“Most of the time the whales ignore [the drone] and if they do look at it, they’ll just turn and then just keep moving,” Sheppard says.

With a target area no larger than two basketballs, the pilot sometimes has to go from a more than 100 metres above the whales down to little more than a metre really quickly so that they don’t miss the breath. “You only get seconds,” says Welch.

Despite the technical challenges of flying drones so precisely, the team is on a mission to succeed. “What we do has to have tangible, real-world benefits for the species that we’re studying,” says Sheppard, “Otherwise we’re just stamp collecting.

“We have to be advocates and we have to push for change. And that’s what the science does – it backs it up.”

2 months ago

60

2 months ago

60