During the final months of 1960, in what is now Gombe national park, Tanzania, Jane Goodall, then 26 years old, made two discoveries that established her name and reputation as a field scientist studying wild apes. First, she observed chimpanzees eating red meat. Before that moment, the scientific consensus, based on virtually no direct observation, was that chimpanzees were vegetarians.

Then she witnessed an even more unexpected behaviour: a chimpanzee male, crouched next to a high earthen tower built by termites, studiously modifying a long stalk of grass until it became a useful probe. The chimp then inserted the probe into a narrow tunnel that descended deep into the mound. As Goodall soon came to understand, members of the insect species’ soldier caste inside the mound instinctively lock their powerful mandibles on to any intruding object – and thus they became, once the probe was carefully drawn back out, victims of a crafty ape. The termites, potentially a significant source of nutrition, were tasty enough to serve as food for several species of monkey in that part of east Africa. Only chimpanzees, however, had developed the cultural tradition of “fishing” for them.

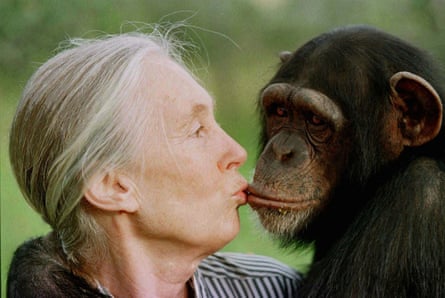

Goodall, who has died aged 91, was not the first person to see wild chimpanzees use objects as tools, but she was certainly the first to observe the behaviour so closely and repeatedly, and to document it thoroughly. That chimpanzees ate meat and used tools were stunning discoveries, and with them Goodall earned her first few paragraphs in the history of primatology.

The project was supposed to end within six months, but Goodall’s discoveries led to renewed support and more research. At a time when animals were usually conceptualised as mindless bundles of reflex and instinct, she came to describe the ones she was studying as deliberative creatures who remembered the past, anticipated the future, planned, had emotional lives and were driven by individual personality and character.

She maintained a regular presence in that forest (personally and then through assistants and associates) for more than 25 years, and even after she retired from active scientific research and moved on to a second career as a conservationist and activist, she kept the research going at the Gombe Stream Research Centre. The Gombe centre today stands as the longest continuously running scientific field station.

Because she did it her way, and because she was determined, courageous, resilient and passionate, Goodall helped to create a new style for the science of animal watching. She showed how to do it. Already the world’s foremost expert on wild chimpanzees, in 1962, without the usual undergraduate degree, she entered Cambridge University as a doctoral candidate in ethology. She gained her PhD in 1966, by which time she was already famous in the US as the author and subject of some astounding National Geographic magazine articles featuring her research. She also wrote a popular book based on that work, In the Shadow of Man (1971), which became an international bestseller.

For a time, her popularity outstripped and even conflicted with her scientific reputation. Wasn’t good science supposed to be boring? The attitude of the time was, how could anyone be so pretty and a first-rate scientist? The zoologist Solly Zuckerman led the charge, publicly chastising her after she had given her first paper at a scientific conference in 1962 as an amateur whose reports on chimpanzee meat-eating were based on “anecdote”. Zuckerman then privately described, in a brief note to the ethologist Desmond Morris, his own “anxiety”, stimulated by Goodall’s conference presentation, “lest a subject which has been usually marked by unscientific treatment should continue in the unscientific shadows because of glamour”.

In spite of such detractors, Goodall’s professional reputation grew. In the early 1970s, she was appointed visiting professor of psychiatry and human biology at Stanford University and of zoology at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. She later held academic appointments at Tufts University, the University of Southern California, and Cornell University in the US. The publication by Harvard University Press of The Chimpanzees of Gombe (1986), summarising the first quarter-century of knowledge about wild chimpanzees gleaned primarily from the Gombe research, prompted an international convention of primatologists at the Chicago Academy of Sciences. The gathering brought with it the sobering consensus that wild chimpanzees were declining and threatened with extinction across Africa, while chimpanzees in cages outside Africa were often being threatened by cruelty and abuse.

In a burst of inspiration, Goodall ended her direct scientific work in order to become an activist. She spent the rest of her life travelling around the world fighting for the future of chimpanzees and other wild species, and ultimately for our own.

Born in London, Jane was the elder daughter of Vanne (Myfanwe, nee Joseph) and Mort (Mortimer) Morris-Goodall. He was heir to funds generated by the family business – manufacturing playing cards – and between the wars was a top driver for the Aston Martin racing team. Vanne was the daughter of a Congregational minister in Bournemouth. She trained as a secretary and worked in London.

Mort and Vanne met in London and married, and when the second world war took him away, she returned with their two young daughters to the family home in Bournemouth. Mort stayed in the army for a few years following the war, rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel, and in 1950 wrote to Vanne asking for a divorce.

Valerie Jane (soon to become “VJ”, then “Jane”) thus grew up with her sister, Judy, in an impoverished but cheerful and nurturing all-female household: grandmother, mother and two unmarried aunts. Her mother believed in the kind of parenting where reason took precedence over rules; and in an era when girls usually faced a narrow path of possibilities, Vanne told her daughter she could do anything she wanted if she tried hard enough. What the young girl wanted more than anything else was to be Tarzan, her hero from the books she read while sitting in the branches of her favourite tree. She wanted to swing through the trees and live among the apes in Africa.

It was a childish dream and yet she was serious. Jane started to study animals. She tamed birds that came to her bedroom window. She learned to ride. She wandered by herself up and down the cliffs, where she became familiar with small mammals. She had from her earliest years an impressive focus.

One day, the opportunity to follow her childhood dream arrived. It came in the form of a letter from an old school friend whose father, in postwar colonial Kenya, had acquired a farm in the hills outside Nairobi. The letter invited her to visit Africa and stay at the farm.

By now she had left Uplands school, Poole, and, following the advice of her mother, acquired work as a secretary: first in Oxford, then London. But after the invitation to Africa arrived, she returned home to Bournemouth and waitressed until she had enough money saved to purchase her one-way passage on a boat. She arrived in Nairobi on 3 April 1957, just in time to celebrate her 23rd birthday. After staying at the farm for a month, she found a room and a secretarial job in town.

But where were the wild animals, and how could she find them? She made the most direct approach possible, which was to introduce herself to the curator of the Coryndon Natural History Museum in Nairobi, Louis Leakey. As a paleoanthropologist, he was determined to follow his conviction that human evolution originated in Africa, and believed that part of knowing the great story required understanding our apeish ancestors’ behaviour, and in studying humankind’s closest living relatives: the African great apes, particularly chimpanzees.

By the mid-1950s, a few astute anthropologists had embraced this idea, but almost no one knew where or how to find the chimpanzees. And far more difficult than finding them would be the problem of getting close enough to study them. They were wild and volatile. And they were many times stronger than the strongest man. They were dangerous, and people were not ordinarily foolish enough to go looking for them without a gun.

Then came Goodall. She made a positive first impression on Leakey and was hired as his secretary at the museum. She was passionate about animals, he recognised, and she showed herself capable of roughing it on safari for extended periods of time.

Leakey decided to organise an expedition into the wilds of western Tanganyika Territory (now part of Tanzania) where Goodall would set up camp within a patch of forest at the edge of Lake Tanganyika that the British had identified as the Gombe Stream chimpanzee reserve. It was a remote location, but chimpanzees could be found in that forest, and perhaps, Leakey imagined, his secretary would discover something useful.

Since the British colonial authorities ruled that no woman was allowed to go into the forest alone, Goodall’s mother agreed to accompany her. They hired a cook in Kigoma, Dominic Charles Bandora. Thus began, in July 1960, the world’s most improbable scientific expedition.

Eventually Goodall received more than 50 honorary degrees, in 2002 was made a United Nations messenger of peace, and the following year a dame. She won the Stott science award from Cambridge University, the Kyoto prize in Japan, and the Kilimanjaro medal from Tanzania.

In 1977 she founded the Jane Goodall Institute, which works to protect chimpanzees and supports youth projects aimed at benefiting animals and the environment. Tireless as an advocate, at the time of her death she was on a speaking tour of the US.

In 1964 Goodall married the wildlife photographer Hugo van Lawick, with whom she had a son, also Hugo. The couple divorced in 1974. Her second marriage, in 1975, to the British-born Tanzanian farmer and politician Derek Bryceson, ended with his death in 1980. She is survived by her son, three grandchildren and her sister.

2 months ago

65

2 months ago

65