Former firefighter Gina Kothe’s right foot was crushed in an aerial-ladder accident during a 2010 blaze in Kingston, New York.

After months of false hope and a failed surgery, doctors decided her foot would have to be amputated. She fell into depression. “I had a slight addiction to painkillers,” she recalled. “I would shower every three or four days, and wear the same barbecue-stained T-shirt for two or three days in a row.”

Her recovery began the day her husband walked in holding a box she assumed was filled with Dunkin’ Munchkins. Instead, it chirped. “He’s like, ‘I got you some baby chicks – you’re probably gonna want to get up.’”

Besides adopting baby birds, Kothe credits spending time outdoors for pulling her out of despair.

The compact 53-year-old Army veteran in a gray T-shirt that reads: “If you think I’m short, you should see my patience,” lives on a farm where she hauls hay and exercises her mobility dog, Opal. She also participates in adaptive sports, including rock climbing and bobsledding.

And on a recent overcast morning, she tried a more tranquil activity: leaf peeping.

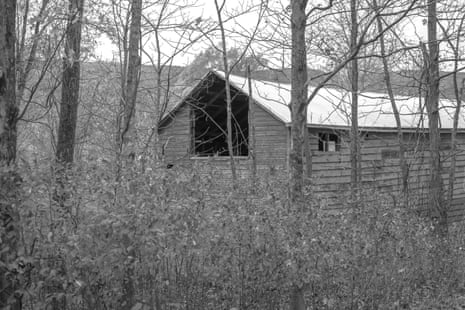

She joined a motorized guided tour of the Mohonk preserve – a 8,000-acre (3,237-hectare) stretch of forest, wetlands and cliffs nested in the Catskills, about 90 miles north of New York City – riding in a Trackchair, a cross between a wheelchair and a tank.

The all-terrain vehicles are slow, set at a top speed of 3mph (5km/h), but steady. They can easily roll over rocks, tree roots, gravel, sand or mud.

The free outing was organized by Soar Experiences, a small non-profit tour operator serving people with limited mobility. (Soar stands for “Specialized Outdoor Adaptive Recreation”). That morning, six guests gathered in Mohonk’s parking lot for a 10-minute primer on operating the joystick-controlled Trackchairs. Guests signed an obligatory liability waiver and listened to a brief safety talk before starting a test course, weaving in and out of orange traffic cones.

Experienced Trackchair user John Vacca, who lost his left leg below the knee because of cancer and now volunteers mentoring fellow veterans and others with amputations, issued a gentle warning about tailgating. “Know your speed,” he cautioned.

While an increasing number of green spaces are investing in improving accessibility, hiking in nature poses natural challenges. “The wood doesn’t care about ADA compliance,” said Peter Gagliardo, adaptive sports coordinator for Helen Hayes hospital, a rehab center in West Haverstraw, New York.

Gagliardo was paralyzed from the waist down when a car struck his motorcycle in 2006. About seven years ago, he and a colleague convinced Scott Trager – who runs an off-road driving school – to install hand controls into one of its Jeeps. The experiment was a hit: off-road enthusiasts with disabilities raved about navigating the school’s 75-acre obstacle course. Soon after, Trackchairs joined the fleet and Trager later launched Soar with his wife and two sons.

A self-described “solutionist”, Trager, 63, once devoted his days to shaving milliseconds off stock trades on Wall Street. His new career as a social entrepreneur, he said with a chuckle, “beats my cubicle” and pays unexpected dividends. “It makes me better understand that life can change in the blink of an eye.”

Now that Soar has secured its non-profit status, Trager hopes to attract more philanthropic support to expand its programmes. In recent months, SOAR held 15 free public hikes primarily at parks in New York and Connecticut; many had waiting lists. “The more we started working with this particular demographic,” said Trager, “the more we realize they are drastically underserved.”

Trager generally avoids asking clients about their disabilities, but many open up anyway. At an event at Green Lakes state park, he met a woman born with stunted limbs who asked if he could take her to the beach in a Trackchair. Once there, she asked him to scoop some sand into her hand.

“She starts crying,” Trager recalled. “I’m like, ‘What’s the matter?’”

She told him she had never felt sand before.

“She got very emotional,” said Trager. “And this is why we’re doing this.”

At Mohonk, the mood among guests was palpably cheerful. The sun burst through, and the oaks and maples exploded in red, orange and yellow. The three-mile loop on the gravel carriage roads wound past babbling streams and verdant fields. Sheer cliffs glistened in the distance.

“I could get used to this,” exclaimed Stephen Fray, 61, who has ALS. The highly reactive battery-powered Trackchairs with motorized tilting seats impressed the former civil engineer (and Boy Scout). But his disease has forced him to prematurely retire and tap his savings so he was skittish about the cost of one: between $13,000 and $27,000.

David Daw, who attended an afternoon session, also seemed ebullient: “I feel free. I don’t feel sick when I’m out here.”

A former stage manager who retired because of muscular dystrophy, Daw now serves as something of a disability rights influencer with a popular Instagram account, Things My Wheelchair Saw. He admitted sometimes struggling with isolation, because “most times you need somebody to drive you somewhere, you need somebody to help you get your chair together”.

“If I had to stay indoors, I’d probably be gone,” said Eddie Slick, 73, who drove two-and-a-half hours to get to Mohonk. The avid hunter and fisher looked the part with his camouflage jacket and a white horseshoe-shaped moustache. The fear of being cooped up pushed him to heavily invest in mobility equipment: he customized his ATV to enable him to continue hunting and installed a crane into his van to lift his motorized wheelchair. But he allowed that if someone facing a significant health struggle lacks resources, “that guy’s really screwed.”

Despite research showing that adaptive sports bolsters mental health – data from the Centers for Disease Control found that people with disabilities experience frequent mental health distress 4.6 times more often than people without disabilities – most insurers refuse to cover adaptive sports equipment.

Insurance companies will not “pay to modify your bathroom”, seethed Gagliardo. “So that means when you’re being discharged from the hospital, you need to put a ramp in yourself. Your bathroom doors aren’t wide enough? That’s your problem. Your $75 grab bar, your shower bench, will not be covered. So, when it comes to sporting equipment, forget about it.”

Complaints about the health insurance industry often come up on the trail. Daw recently battled his insurance company for 16 months to receive reimbursement for his motorized chair. He had a prescription from his doctor, but his insurance company forced him to see various specialists to confirm the diagnosis, which often meant long waits for appointments and hours on the phone.

“You have to play all those games,” said Daw, who called for legislation to stop insurers from procrastination. He argues 90 days should be long enough for insurers to approve or deny medical equipment for customers with disabilities.

“They’re hoping you give up,” Daw fretted. “Because most people give up. Some of them commit suicide. I almost did.”

Kothe, the former firefighter, recently fell at home and reopened the residual limb scar wound below her right knee. Despite the significant bleeding, she refused to go to the nearest emergency room. She assumed doctors at a hospital would close the wound with stitches, which would probably alter the fit of her $23,000 prosthesis. Kothe doubted that her insurance would cover the expense. Instead, she relied on DIY medicine: Dermabond skin glue, a Maxipad with antibiotic cream wrapped by an Ace elastic bandage. Fortunately, her repair worked.

Arguably, insurers have a penny-wise mentality. For instance, lightweight carbon fiber or titanium wheelchairs are routinely deemed not medically necessary. But hi-tech chairs, explained Dr Brooke A Slavens, director of the mobility laboratory at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, “reduce wear-and-tear on the shoulder and may lessen the risk or severity of injury over time”. She estimated that 90% of adult manual wheelchair users ultimately deal with shoulder injuries, such as tendinitis and rotator cuff tears. Shoulder surgeries, however, are typically covered expenses.

Research supports the commonsense premise that time in nature is time well spent. A metanalysis in the journal Healthcare found that “engagement in adaptive sports showed a positive impact on the mental quality of life among adults with physical disabilities”.

An article published by the American Psychiatric Association cited a Japanese study that monitored a group of people walking in a city and a forest. Subjects on country jaunts had “12% lower stress hormone levels, as well as decreased blood pressure and heart rate and boosted immune function”.

Gagliardo does not need to see brain imaging scans to know that the outdoors improves the lives of people coping with profound trauma.

“When you do get into an off-road Jeep or an off-road wheelchair, everybody’s face just absolutely lights up,” he said at Soar’s headquarters. “They’re tackling something that everybody told them was impossible. That they told themselves was impossible. Until they come out here and realize – it’s all possible.”

1 month ago

62

1 month ago

62