The seaside city of Southend-on-Sea, on England’s east coast, looks grey on a winter afternoon in term-time. Its cobbled high street, bordering the university campus, is sparsely populated with market stalls, vape shops and discount retailers, and feels unusually quiet.

“There used to be lots of shops, restaurants and youth clubs around here,” says 23-year-old Nathan Doucette-Chiddicks. Now, the city is about to lose something else that it can scarcely do without.

Just before Christmas, Essex University announced that it would close its Southend campus this summer due to a big fall in international students, who pay much higher fees. The move will affect 800 students, as well as staff, but it will also have a huge impact on a city that has come to depend on the university in many ways.

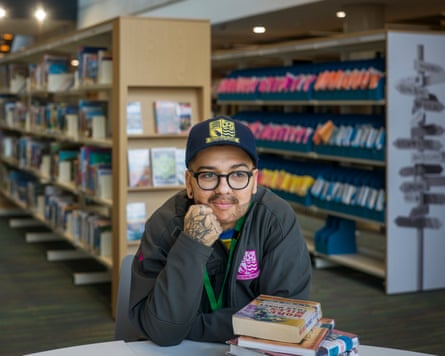

Doucette-Chiddicks, a student on the adult nursing course, describes himself as Southend “through and through”. He wears Southend United merchandise from head to toe and has lived in the town all his life.

His mother was one of the university’s first students when it opened in 2008. “She used to sneak me into the computer labs so she could study,” he recalls.

The campus is just a few doors from his home and, for him, has long symbolised possibility for the people who live here. His mother is now an A&E nurse and he wants to follow in her footsteps.

“It’s a big loss,” he says. “Not just for students – for the city as a whole.”

What is the Against the tide series?

ShowOver the next year, the Against the Tide project from the Guardian’s Seascape team will be reporting on the lives of young people in coastal communities across England and Wales.

Young people in many of England's coastal towns are disproportionately likely to face poverty, poor housing, lower educational attainment and employment opportunities than their peers in equivalent inland areas. In the most deprived coastal towns they can be left to struggle with crumbling and stripped-back public services and transport that limit their life choices.

For the next 12 months, accompanied by the documentary photographer Polly Braden, we will travel up and down the country to port towns, seaside resorts and former fishing villages to ask 16- to 25-year-olds to tell us about their lives and how they feel about the places they live.

By putting their voices at the front and centre of our reporting, we want to examine what kind of changes they need to build the futures they want for themselves.

Across Essex University, which also has a campus in Loughton, 18% of students are local, but in Southend, for students training to work in health or social care, that figure leaps to 52%. Doucette-Chiddicks describes a sense of community rarely found in larger universities. “My lecturers know my mum and they know me,” he says. “A lot of them studied here before becoming lecturers.”

Seventeen years ago, the arrival of a university in the centre of what was seen as a “left behind” seaside resort was positioned as a clear message of hope. Its £26m glass building, with striking views of the Thames estuary on one side and a derelict office block on the other, was there to kickstart the town’s flagging economy.

It was a sign that young people growing up here could have bigger aspirations – that Southend was a town on the up.

Colin Riordan, who was vice-chancellor of the Essex University at the time, recalls the optimism when they set up the Southend campus. “We wanted the university to be a place people felt part of,” he says. “We wanted to create a campus feel but one that was there for local people.”

When it opened, the campus housed a GP surgery and a new dental clinic offering free treatment to local people. This was followed later by the forum – a library and art gallery shared by the university and local people.

Riordan recalls watching a performance of Frankenstein in the church that Southend’s acclaimed acting school, East 15, took over as a theatre and performance space.

“I remember sitting on the edge of my seat because it was an amazing performance,” he says. “And it was extra exciting because this was a town that didn’t have much access to culture before.”

Over a few years, Riordan watched Southend changing: “It really did go from a place that felt like it needed attention to somewhere much more vibrant.” Suddenly it felt like there were “young people everywhere” – and independent shops and cafes were opening up to cater for them, he says.

Riordan, who went on to run Cardiff University, which has also been in the headlines over dramatic job cuts, is pragmatic about Essex making tough decisions to keep its head above water. He observes that the Southend campus was established at a time when the New Labour government was intent on making sure as many people as possible could go to university, with Southend one of the first of a grand (and never fully realised) vision for 20 new university towns in higher education “cold spots”.

“Back then there was a clear national vision for universities, and they were mostly publicly funded,” he says. “Now you stand or fall on your student demand.”

Yet the end of the Southend university dream still upsets him. “It is a great pity. It was a wonderful project,” he says.

In Southend today, alongside the more concrete impact on students, the job losses (which will hit catering staff and cleaners as well as academics) and the threat to local businesses, many people are also depressed about the symbolism of what it will mean to be a city that used to have a university.

George Bejko-Cowlbeck, director of Caddies crazy golf, where students come to drink and play in the giant disco ball pit as well as putting balls, says he has spoken to students who love Southend and do not want to leave. He moved here when he was 17 and remembers that the seaside town “felt fun, like running away to join the circus”.

Students are big customers for Caddies, and the drama school is an especially good source of effervescent part-time staff. But he senses Southend will be losing more than just cash. “Having the university here was a big part of the city’s feeling of youthfulness, and the idea that you can be here and learn and grow.”

Lauren Ekins, a Southend primary school teacher who grew up here in the days before there was a university, says: “If I think about what this means for the children who are at school here now, I want to cry. So many children have lost access to their potential futures.”

During a stay in hospital for surgery recently, Ekins met a former pupil. “She was studying to be a nurse and that was so lovely,” she says. “She was from a deprived background and university wasn’t necessarily in her future – but it was here.”

Southend, which is only 60 miles outside London, has some pockets of wealth, but Ekins says lots of families are living on the breadline. She is angry that the government bailed out banks but will not step in to save universities in deprived cities such as Southend. “I feel like they are leaving us behind,” she says.

Bayo Alaba, the Labour MP for Southend East and Rochford, sees the university as a “clear ladder to social mobility”, noting that students of subjects such as midwifery, social care and nursing are “disproportionately poor members of the local community who often have caring responsibilities”.

The university is worth more than £100m a year to Southend’s economy, Alaba estimates. Small local businesses including cafes, bars, taxi firms and shops are braced for the loss of student customers. But he adds: “This sends the subliminal message to people who want to invest in the city or expand their business that they should be looking elsewhere.”

Alaba feels the “harsh decision” was sprung on the community without warning. The university informed Alaba and his fellow Southend MP, David Burton-Sampson, out of the blue a fortnight before Christmas, he says. “It wasn’t even a sit-down meeting. It was a quick 20-minute zoom call and the decision had already been made.”

“They have seen these challenges for a while,” he adds. “They should have been putting contingency plans in place and priming the council.”

Prof Frances Bowen, Essex University’s vice-chancellor, says: “Closing the Southend campus was an incredibly difficult decision, which we only took after reviewing all reasonable alternatives and was a decision we could never previously have imagined.”

The university has said all Southend students can finish their courses at its Colchester campus, which is 45 miles away. But Alaba says a two-hour commute each way on public transport is not feasible for many students; many cannot afford the travel costs or cannot fit it in alongside caring for their family or holding down a job.

“Some students have already dropped out,” the MP says. “They have taken on debt for something they thought would change their life.”

Radek Hanus, a mature student in his second year of a nursing course, has lived in Southend for four years. He only found out that the university was closing when he saw an article in the local paper during a shift on his nursing work placement.

“It’s a joke,” Hanus says. “I’ve lost two years of time and money and education. People are devastated.”

Hanus is registered disabled due to his Crohn’s disease. “Commuting to Colchester will cost me something like £800 a month in petrol. How can I possibly afford that?”

Doucette-Chiddicks already works long hours to pay his rent alongside studying. However, he is resolute: “There are some people who have decided to quit, or they’ve just not been turning up to lessons. But I’m going to finish my degree.”

By late afternoon, a fine drizzle begins to fall, deepening the gloom along the high street. The owner of a nearby business, who asked not to be named, describes the closure as “catastrophic” and part of a wider decline of many coastal places that is affecting Britain’s young people.

“How can you have a city without a university?” he asks. “It’s shocking.”

-

The Against the tide series is a collaboration between the Guardian and the documentary photographer Polly Braden and reports on the lives of young people in coastal communities across England and Wales

3 hours ago

3

3 hours ago

3