At the southern tip of Europe’s largest river island, the ground falls away into a vast and unexpected vista. From a high, rocky ledge on Khortytsia Island, the view opens on to a sea of swaying young willows and mirrored lagoons. Some of the trees are already many metres tall, but this is a young forest. Just a few years ago, all of it was under water.

“This is Velykyi Luh – the Great Meadow,” says Valeriy Babko, a retired history teacher and army veteran, standing on the former reservoir shoreline at Malokaterynivka village. For him, this extraordinary new-old environment represents more than nature alone.

“It is an ancient, mythic terrain, woven through Ukrainian folklore,” he says. “Think of all those Cossacks galloping through its valleys of forests so dense the sun barely pierced them.”

That historic landscape vanished in 1956, when the Soviet Union completed the Kakhovka dam and hydroelectric power plant and flooded the entire region. What had once been an ecological and cultural cradle became a reservoir, and its rich, living systems were entombed beneath the water.

-

Water flows over the collapsed Kakhovka dam on 7 June 2023. Photograph: AP

Then, in 2023, that water was unleashed as weapon: the Nova Kakhovka dam on the Dnipro River, under the control of Russian forces, was blown up (Russia denies bombing it). It sent a vast, destructive flood of water and sediment downstream, destroying villages and killing an unknown number of people; figures for the death toll range from a few dozen into the hundreds. Up to one million people lost access to drinking water. Two years on from the disaster, the reservoir’s future still hangs in the balance. Scientists say it represents both a “return to life” for the ecosystem and wild creatures that inhabit it – and an unpredictable, potentially toxic “timebomb”. It is a case study in the complexity of how nature responds to vast changes wrought by humankind – and what happens to ecosystems in the wake of disaster.

Spontaneous regeneration

In the immediate aftermath of the bombing, Kakhovka reservoir resembled a desert of drying mud and cracked silt. Now, plants grow so thickly you must scythe through the vegetation covering the earth embankment before the basin comes fully into view.

The bone-dry former shoreline is studded with husks and shells of aquatic organisms that once lived here. Beyond it, a vast sea of young trees stretches over the horizon towards the occupied Zaporizhzhia nuclear power station. The size of it is difficult to take in: the reservoir’s surface area was 2,155 sq km (832 sq miles) – bigger than New York City and its five boroughs.

The latest report from the Ukrainian War Environmental Consequences Work Group (UWEC) confirms what satellite images, ecologists and field researchers began to observe over the past two years: the ecosystem of the lower Dnipro is not only recovering, it is evolving. The drained reservoir is now home to dense growths of willow and poplar and enormous wetlands; endangered sturgeon have returned to waterways; wild boar and mammals to the forests; and there are signs of spontaneous regeneration across a huge stretch of floodplain.

“We are witnessing the emergence of a massive natural floodplain forest system,” says Oleksiy Vasyliuk, co-author of a 2025 report on the reservoir for the UWEC and head of the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group. “It is not a managed project. It is the land itself returning to life.”

-

Instead of an artificial lake on their doorsteps, Malokaterynivka residents have a new forest landscape to contend with. Photograph: Vincent Mundy

That return is increasingly measurable for ecologists. “Native fauna are returning to the section of the river freed from the dam and reservoir,” the report confirms. “As well as a rapid expansion of native vegetation, as many as 40bn tree seeds have sprouted, which could lead to the formation of the largest floodplain forest in Ukraine’s steppe zone.”According to Eugene Simonov, international coordinator at Rivers without Boundaries, what is unfolding in Velykyi Luh is not just a local wetland rebound, it is the rare and spontaneous reconstitution of a vast riverine ecosystem, with implications that stretch far beyond Ukraine.

“Prior to the dam, the Dnipro floodplain here hosted huge oak forests and many types of wetlands over thousands of square kilometers, creating a mosaic of biodiversity-rich habitats for hundreds of bird species and gigantic fish such as the Ukrainian sturgeon, which used to come here to spawn,” Simonov says.

-

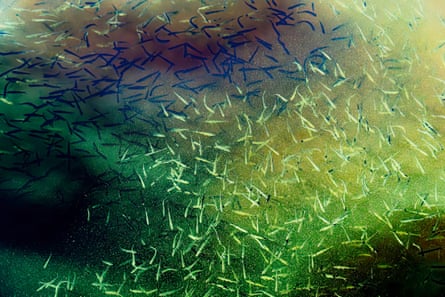

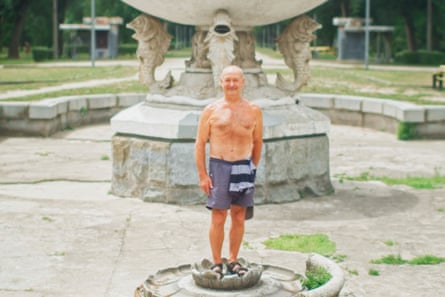

Clockwise from top left: Critically endangered sturgeon are returning to their ancient spawning grounds; billions of freshwater clams died when the reservoir emptied; young sturgeon at a caviar aquaculture facility – a small wild population is now found in the Dnipro; the fountains in Dubovy Gai (Oak Park), which will not work again now the water supply has dried up, says Valeriy Babko, pictured; the floodplain is littered with the remains of aquatic organisms. Photographs: Vincent Mundy

The Great Meadow, he says, also represents an opportunity for Ukraine as it seeks to attract global funds for postwar recovery and join the EU. “Restoring natural freshwater ecosystems along a 250-km stretch of the lower Dnipro could be the largest project of its kind in Europe and has the potential to become Ukraine’s decisive contribution to meeting EU commitments to restore rivers to their natural state by 2030,” he says.

Yet, as scientists are quick to emphasise, this recovery is not guaranteed. Much of the former reservoir remains inaccessible due to active shelling and mined terrain. Comprehensive biological monitoring is difficult. Heavy metals and chemical contamination are a growing concern for researchers. And the future of the area remains politically uncertain.

-

Clockwise from top left: trees sprout from the basin of the former reservoir; Vadym Maniuk, ecologist, surveys the dense growth; white willows and black poplars have grown rapidly, turning the area into forest; some of the trees have already grown many metres tall. Photographs: Vincent Mundy and Alessio Mamo

A ‘toxic timebomb’

While the reservoir forest looks like an oasis, sprung up in the absence of people, it is still marked by the residue of human enterprise. Over time, the banks of the reservoir eroded. Their fine particles of dust sank into a thick layer at the basin’s floor. At the same time, pollutants were entering the water – particularly heavy metals from industrial enterprises along and upstream of the reservoir.

Oleksandra Shumilova, a freshwater ecologist, says: “All these pollutants were absorbed into these fine particles that were deposited on the bottom.” The sediment acted “like an enormous sponge that was accumulated on the bottom of this reservoir. We estimate that it was about 1.5 cubic km of polluted sediments”.

-

The industrial chimneys of Zaporizhzhia tower over the ancient Scythian burial monuments of Khortytsia island. Photograph: Vincent Mundy

When the dam was drained it sent an enormous quantity of polluted, potentially toxic waste flowing into the wider area. Its heavy metals could easily contaminate water sources, soil, and be taken up by plants. Even in small concentrations, they can “have negative effects on virus systems of human organisms, for example, they can cause cancer, endocrine disruptions, problems with lungs, with kidneys,” Shumilova says. She compares their effects to radiation: as those toxins move up the food chain, they can concentrate, causing particular problems for bigger animals and meat eaters.

“As for how these pollutants are also transferred within the food web, it’s not known. It is not possible to investigate at the moment, because it’s dangerous to enter the area. There is no systematic research,” she says.

-

With the Dnipro River’s water table permanently altered, the artificially fed ponds in Dubovy Gai are expected to be fully dried out by the end of the summer. Photograph: Vincent Mundy

A 2025 report co-authored by Shumilova and published in the journal Science concluded that the pollutants represented a “toxic timebomb”, and warned of significant concerns for animal food webs and human populations living in the area. But, as in other environments – such as the site of the Chornobyl nuclear disaster – contamination and natural regeneration can occur side by side. In the same paper, the scientists concluded that within five years, 80% of the ecosystem functions lost to the dam’s presence will be restored and that the floodplain’s biodiversity would recover significantly within two years.

A rare opportunity

The UWEC report frames this moment as a strategic turning point for Ukraine’s environmental and cultural policy. If left to regenerate, the site could become one of Europe’s largest contiguous freshwater ecosystems, rivalling even the Danube delta in ecological importance. But the emerging forest at Kakhovka could disappear as quickly as it emerged.

“If the hydropower dam is rebuilt,” Vasyliuk warns, “this young forest and all the life it now sustains will be lost again.”

The state energy company Ukrhydroenergo has already signalled its intention to reconstruct the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant. For some officials, this represents a return to “normality”: a reinstatement of industrial productivity, energy security and geopolitical control.

“Rebuilding the dam the way it was would not be a recovery,” says Vasyliuk, “it would be an ecocide. It would destroy a young, spontaneous forest before we even have a chance to understand it.”

The decision holds significance beyond Ukraine’s borders. Roughly 80% of the territory affected by the reservoir’s collapse lies within nationally and internationally protected zones, many of them part of Europe’s Emerald Network, placing the fate of Velykyi Luh within a larger continental mandate to safeguard ecological and cultural heritage.

-

People fish in the river, which dropped by several metres after the dam was destroyed. Photograph: Vincent Mundy

From a climate perspective, the newly forming ecosystem offers significant potential for carbon capture and storage, the 2025 UWEC report concludes.

“This is an opportunity we cannot afford to miss,” says Simonov. “If Ukraine chooses to protect Velykyi Luh, it won’t just be saving a landscape, it will be choosing to believe in its own future.”

“This is our biocultural sovereignty at stake and that means our nature, our identity, our independence, and a symbol of the kind of nation we want to become.”

Across the lower Dnipro, warblers nest in reeds where water once lapped against concrete and sturgeon spawn in shallows they haven’t visited in 70 years. The new wetland echoes an ancient rhythm.

“What will happen with this area? We cannot predict at the moment with full confidence, but it’s true that it is reestablishing very rapidly,” says Shumilova.

“From a human point of view it was, of course, a disaster for people living there. But from a scientific point of view, it’s a very rare event: how an ecosystem [can be] re-established. It is a big natural experiment. And it is still ongoing.”

-

Beyond the riprap (rocks placed at the shoreline to control erosion) of the former reservoir the new forest emerges. Photograph: Vincent Mundy

Additional reporting by Tess McClure

Find more age of extinction coverage here, and follow the biodiversity reporters Phoebe Weston and Patrick Greenfield in the Guardian app for more nature coverage

3 months ago

134

3 months ago

134