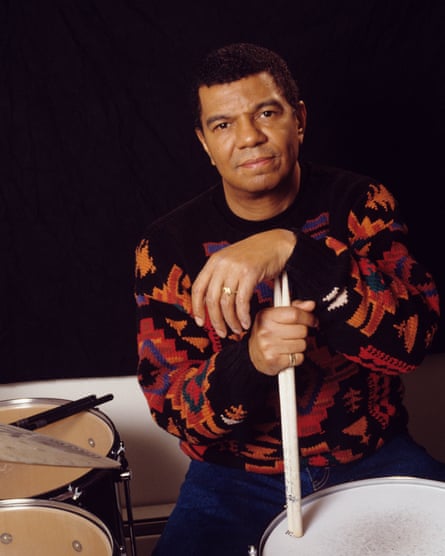

My interview with Jack DeJohnette didn’t start well. It was the summer of 2000 and DeJohnette was in London to play with Keith Jarrett’s Standards Trio. Referring to him in my first question as a “drummer” felt reasonable enough, but DeJohnette didn’t appreciate being pigeonholed and shot back instantly: “I’m a complete musician.” A few days later, sitting in the Royal Festival Hall watching the Standards Trio, a moment of transcendent magic thrilled me as Jarrett sustained a long sequence of repeated notes high up on the piano and DeJohnette powered the music forwards with a labyrinthian drum solo as harmonically searching as anything Jarrett had played. Complete musician indeed.

“The idea of improvisation,” DeJohnette told me, “is tied up in the very nature of our existence. We don’t expect our life to evolve without changing and we never know what’s round the corner – why should music be any different?” He further explained that each part of his drum kit he considered to be a musical being “in its own right”. He designed and tuned his cymbals to his own specification. Mix the sound of cymbals with the drums and then “you think harmonically on the kit,” he added. The sounds inside DeJohnette’s head could never be contained by the conventions of drum technique. He was also a pianist of considerable merit – who released a solo piano album, Return, in 2016 – and every facet of his musicianship seemed to be on display all of the time, until his death this week aged 83.

Many drummers tune their kit to a bespoke design, but DeJohnette’s playing exhibited a life-force that was entirely his own. To hear him play on What I Say from Miles Davis’s album Live-Evil is to marvel at apparently superhuman drive as he maintained an impactful funk/rock beat for 20 minutes. DeJohnette, who also played on Davis’s epoch-defining Bitches Brew, had by 1970 become the trumpeter’s drummer of choice in a meeting of mighty musical minds. His drums rooted What I Say deep in the Earth and allowed Davis, and subsequently saxophonist Wayne Shorter, all the space they needed to explore, while DeJohnette packed his playing with rattling rhythmic asides – keeping a continual discussion with the other musicians.

His own 1968 debut album, The DeJohnette Complex, immediately proposed that his was a voice intimately connected with a jazz scene exploding in a thousand directions around him, while he remained doggedly independent. The compositions DeJohnette wrote for his album were harmonically ornate and asserted jazz/rock energy while also occasionally leaning towards free-form improvisation. He featured himself playing melodica, and his folky melodic inventions soared.

The DeJohnette Complex demonstrated that DeJohnette’s aesthetic was indeed delightfully complex and, after leaving Davis, he was signed to ECM Records. In 1976 he released Untitled, a hectic quintet album, but also Pictures in which he played piano, drums and organ, and duetted on some tracks with guitarist John Abercrombie, an album that was sparse and bare-bones in contrast to Untitled.

His 1981 ECM album with saxophonist John Surman, The Amazing Adventures of Simon Simon, became a landmark moment for both musicians, and a much-loved classic too. Surman and DeJohnette played their usual instruments while also doubling on keyboards and synthesisers, subsuming their own identities inside lavishly orchestrated soundscapes of pastoral tones. Another essential album was Oneness, recorded in 1997, which dealt up large-scale structures with pieces such as Free Above Sea and Priestesses of the Mist, their titles mirroring the elemental force unleashed by the music. Listening to that album around the time of its release, I was reminded of an earlier encounter with DeJohnette, when I heard his group Special Edition play in Leeds during the late 1980s. This performance was in no hurry to stake out its terrain, as ambient, slow-burn forms gradually telescoped towards rhythmic blows.

Talking to DeJohnette all those years later, these ideas of stress-testing form and scale made more sense. He told me how he loved playing those funk figurations with Davis because “I could sit in grooves and let them saturate me”, but also spoke of his desire to generate more wide-angled musical soundscapes, always open-ended and therefore healthy for the brain. He complained about the “safe confines” of pop music with its repetitive patterns. “With improvisation, though,” he said, “you’re open to a full range of possibilities. People are capable of being very creative but only seem to tap into their potential when there is a major earthquake or something. But if people were more conscious of our place within nature, stopped abusing the Earth and put things back into it, we would have a healthier environment and society.”

No question that DeJohnette heard his music as modelling those idealist aspirations. “Art is the spiritual equivalent of that purification, which is passed to us as energy – and all artists have to draw on that.”

2 months ago

58

2 months ago

58