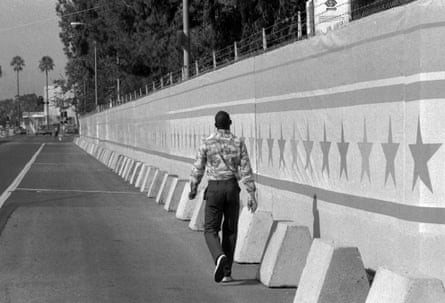

In the lead-up to the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles, the city deployed 30 police officers on horseback to rid downtown of unhoused people and, in the words of a captain, “sanitize the area”.

Some people were arrested and transported to detox centers. Others were forced from public view while their possessions were trashed.

Now, as the city prepares to host the games once more in 2028, civil rights advocates are fearful history will repeat itself, and authorities will again banish unhoused communities in ways that could exacerbate the region’s humanitarian crisis.

Karen Bass, Los Angeles’s Democratic mayor, has vowed not to bus unhoused people out of the city and repeat the tactics of 1984, telling the Los Angeles Times her strategy will “always be housing people first”. But the scale of the problem in LA is larger than it was four decades ago, and the Trump administration’s forceful stance on homelessness could increase pressures on Bass and the unhoused population.

LA county is home to an estimated 72,000 unhoused people, including 24,900 people in shelters and 47,400 people living outside in tents, makeshift structures and vehicles. In the last two years, Bass and county leaders have reported some progress in moving people indoors, which they attributed to their strategy of targeting people in encampments with shelter options and resources.

But the dramatic shortage of affordable housing in the region will make it difficult to get tens of thousands of people stably housed in less than three years and stop new encampments from rising up.

Meanwhile, Trump, who appointed himself White House Olympics taskforce chair, has made it clear he wants to see encampments disappear from American cities, signing an executive order in July to push local governments to clear encampments and making it a point of focus during the federal crackdown in Washington DC.

Combined with a supreme court ruling allowing governments to fine and jail unhoused people when no shelter is available, Trump’s ongoing deployment of troops to Democratic cities, significant support from California residents for tougher policies towards the unhoused, and California governor Gavin Newsom’s push for aggressive sweeps, experts fear the Olympics could force out many of LA’s poorest residents.

“The pressures are going to come from the White House, from the state and from local government as we get closer to the Olympics,” said Pete White, executive director of the Los Angeles Community Action Network, an anti-poverty group that advocates for unhoused people and is based in Skid Row, a downtown area with a high concentration of homelessness. “My fears come from being an Angeleno and seeing our communities attacked and displaced when major events come our way.”

‘I remember the arrests’

There is a long history of Olympics host cities trying to get rid of their most disenfranchised communities.

In Moscow in 1980, organizers pledged to “cleanse” the city of “chronic alcoholics” and dumped people outside city limits. In Atlanta in 1996, officials arrested thousands of unhoused people under anti-loitering and related ordinances. In Rio de Janeiro in 2016, more than 70,000 people were displaced. And last year in Paris, thousands of unhoused people, including asylum seekers, were bussed out.

The 1984 LA games led to the increased militarization of the LA police department (LAPD) and an escalation of racist and aggressive policing that targeted Black and Latino youth, experts say.

“I remember the pre-Olympics arrest of my older cousins,” said White, 56, who grew up within walking distance of the Coliseum, a stadium that served as an Olympics venue then and will be used for the 2028 opening and closing ceremonies. “Young Black and brown men were afraid to be in the streets, because they were sweeping people up under the pretext of addressing gang violence.”

The games helped LAPD acquire flashbang grenades, specialized armor, military-style equipment and an armored vehicle, which it used a year later to ram a home where small children were eating ice cream, Curbed LA reported. The Olympics-fueled law enforcement expansion also paved the way for LAPD’s notorious Operation Hammer, a crackdown that led to mass arrests of Black youth.

In 2018, after LA won the 2028 bid, then-mayor Eric Garcetti said the games would present an opportunity to improve homelessness, which he said could be eliminated from the streets by the games.

“Garcetti kept saying: ‘We’ll end homelessness in LA,’” said Eric Sheehan, a member of NOlympics, a group founded in 2017 to oppose the Olympics in LA. “And we have been warning that the only way they can actually end homelessness is by disappearing people.”

Increasing sweeps

California, LA and LA 2028 officials have not released plans for a homelessness strategy.

But on the streets, there are already fears that sweeps of people living outside are escalating due to the Olympics – and as LA prepares to also host the World Cup next year.

In July, the city shut down a long-running encampment in the Van Nuys neighborhood in the San Fernando valley, north-west of downtown and visible from the 405, a major freeway. The site, which residents called the Compound, was across from the Sepulveda Basin where the Olympics is planning events. The sweep displaced roughly 75 people. The city said it offered 30 motel rooms to the group and other shelter options.

Carla Orendorff, an organizer working with the residents, said she was aware of at least 10 displaced people now back on the streets, including several who had been kicked out of the motels, which have strict rules. Residents were dispersed to eight motels, and in one, staff ran out of food and people were left hungry, she said.

Those still out on the street “are just forced further underground, in places that are harder to reach, which makes it incredibly dangerous for them”, Orendorff said.

Giselle “Gelly” Harrell, a 41-year-old displaced Compound resident, said she lost her motel spot after she was gone for several days. She was temporarily staying in a hostel with help from a friend, but would soon be back in a tent, she said. Before the Compound, she was at another major encampment that was swept.

“They’re strategically cleaning out the area for the Olympics,” Harrell said. “They’re destroying communities. It’s traumatizing … I wish all that money for the Olympics could go toward housing people … but they are not here to help us.”

It was hard to imagine the Olympics taking place in an area where so many people were living outside and in cars, Orendorff added: “The city has all these plans, but our people don’t even have access to showers.”

Bass denied that the Compound closure was Olympics-related, with the mayor telling reporters the site was a hazard. Officials had worked to shelter everyone and keep people together and would aim to transition residents into permanent housing, she said, while acknowledging some “might be in motels for long periods”. “I will not tolerate Angelenos living in dangerous, squalor conditions,” she added.

The mayor’s office continued to defend the Van Nuys operation in an email last week, saying an outreach team had built relationships with encampment residents over several months and offered resources to all of them: “Coming indoors meant access to three meals a day, case management and additional supportive services.”

Zach Seidl, Bass’s spokesperson, did not comment on the city’s Olympics strategy, but said in an email that since the mayor took office, street homelessness had decreased by 17.5% and placements into permanent housing had doubled: “She is laser-focused on addressing homelessness through a proven comprehensive strategy that includes preventing homelessness, urgently bringing Angelenos inside and cutting red tape to make building affordable housing in the city easier and more efficient.”

Inside Safe, Bass’s program addressing encampments like the Compound, has brought thousands of people indoors and “fundamentally changed the way the city addresses homelessness by conducting extensive outreach, working with street medicine providers and offering other supportive case management services while they are in interim housing”, he continued. “This is why she ran for office and this is progress she would’ve made regardless of the Games.”

The White House did not respond to inquiries about the Olympics, and a spokesperson for Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority (Lahsa), the lead public agency responsible for addressing homelessness in the region, declined to comment.

‘Legal restraints are gone’

Advocates’ concerns are partly fueled by a supreme court ruling last year that gave local authorities significantly more leeway to criminalize encampments.

“The legal restraints are gone, to the extent they were meaningful, and there is broad policy-level agreement by liberals and conservatives that sweeps are an acceptable approach,” said John Raphling, associate director of Human Rights Watch, a non-profit.

He authored a report last year on LA’s policing of unhoused people, which found that unhoused Angelenos were routinely subject to aggressive LAPD crackdowns, misdemeanor arrests and sweeps that destroy their belongings.

Homelessness-related arrests and citations, such as anti-camping violations, increased 68% in LA in the six months after the supreme court ruling, a recent CalMatters analysis found. The crackdowns are happening even as LA has vowed to not rely on criminalization and has promised a more restrained approach than other California cities.

Sheehan said he was concerned LAPD would work with federal authorities to target people during the Olympics, especially after officers aggressively attacked protesters and journalists during demonstrations against Trump’s immigration raids in June, in violation of the department’s own protocols.

Newsom, meanwhile, has pushed California cities to ban encampments by adopting ordinances that make it a violation to camp in the same spot for three days, and advocates fear his presidential ambitions could lead him to continue to push punitive strategies as the Olympics approaches.

“We’re already seeing a contest between Trump and Newsom as to who is going to appear tougher on homelessness, with tough being defined as how one responds to visible homelessness,” said Gary Blasi, professor of law emeritus at the University of California at Los Angeles, who co-wrote a report last year on the 2028 Olympics in LA and the unsheltered population. “There aren’t good signs from either of them. Newsom offers the promise of alternatives he doesn’t identify and Trump offers the promise of some equivalent to incarceration.”

In a statement to the Guardian, Newsom said the state has a “strong, comprehensive strategy for fighting the national homelessness and housing crises” and was “outperforming the nation”. “I’ve emphasized that our approach is to humanize, not criminalize – encampment work is paired with shelter, services [and] behavioral health support,” he said, citing his Care court program, which is meant to compel people with severe psychosis into treatment.

“Bottom line: encampments can’t be the status quo. We’re cleaning them up with compassion and urgency, while demanding accountability from every level of government. There is no compassion in allowing people to suffer the indignity of living in an encampment for years and years,” the governor added.

Tara Gallegos, Newsom’s spokesperson, said the governor’s approach was distinct from the president’s, writing in an email: “The Trump administration is haphazardly bulldozing and upending encampments without creating any sort of supportive strategy to go along with it. It is about fear, not support … California’s strategy pairs urgency with dignity and care, creating wrap-around services addressing the root causes of homelessness.”

An LA 2028 spokesperson did not comment on homelessness, but said in an email: “We work closely with our local, state and federal partners on Games planning and operations, and remain committed to working collaboratively with all levels of government to support a successful Games experience.”

Organizers and providers prepare

Homelessness service providers and advocates said they hoped LA officials would pursue bold solutions that quickly get people housing and resources without the threat of criminalization.

A key part of the region’s strategy during the early pandemic was getting people out of tents and into motels, but those programs are costly and not a good fit for all of LA’s unhoused residents; it can also be challenging to transition participants into permanent housing. Blasi noted that that approach would become even harder during the Olympics when hotels face an influx of tourists.

Blasi advocated for direct cash payments to unhoused people, akin to the 2020 stimulus checks, which could help some unhoused people get off the streets at a faster and cheaper rate than the traditional process, he argued: “There are a lot of people who can solve their own homelessness if they just have a little bit more money.”

Alex Visotzky, senior California policy fellow at the National Alliance to End Homelessness, said LA has seen success with rapid rehousing programs that offer people rental subsidies, and that he hopes those efforts can be scaled up: “We know how to move people back into housing and do it quickly. It’s just a matter of whether we can marshal the political will to bring the money to make that happen.”

Funding cuts, including from Trump’s slashing of federal homelessness resources, will be a barrier.

The Union Rescue Mission, a faith-based group that runs the largest private shelter in LA, has recently seen an influx of people needing services as other providers have faced cuts, said CEO Mark Hood. Hood, however, said he has had productive conversations with the Trump administration and remained optimistic the Olympics would provide an “opportunity to collaborate with our city, county, state and federal government in ways that we never have before”.

He said he hoped the Olympics would lead to increased funding for providers, but was so far unaware of any specific plans.

White, the longtime organizer, said he expected grassroots groups to come together to defend unhoused people, especially as mutual-aid networks have grown in response to Trump’s raids: “The kidnappings of immigrants and the attempted clearing of houseless people as we get closer to the Olympics gives us an opportunity to bring various communities together, and that’s when we can build the power necessary to push back.”

2 months ago

66

2 months ago

66