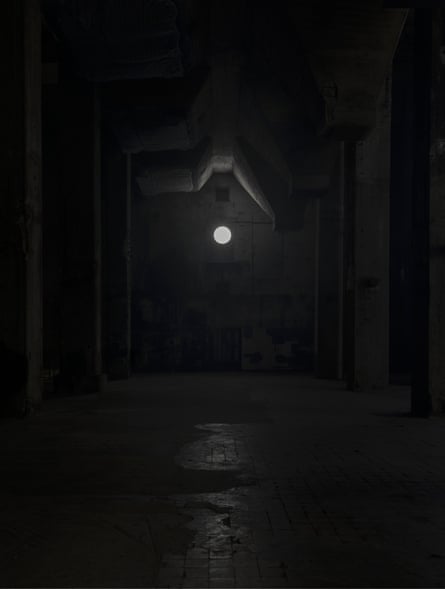

Go up the concrete stairs, cross the concrete floor and mind the concrete pillars. People are groping about in the darkness, waiting for their eyes to adjust, though most give up and start navigating by the light of their smartphones, trying to find Pierre Huyghe’s new work without quite realising they are already in it. Huyghe’s Liminals is more than just a film projected on a towering screen in a gutted power station. It is a quantum experiment, a mythological journey and a terrifying vision, set to a shifting thrum of gut-wobbling vibrations, a sizzling aural rain of dancing particles and sudden ear-splitting crackles which ricochet everywhere. You can’t always tell what’s happening on the screen and what’s happening in the cavernous space around you.

I could feel the vibrations even on the street outside, looking up at the brooding hulk of the defunct 1950s power and heating plant that once serviced the socialist paradise of postwar East Berlin. Now the home of the world’s most famous techno venue, Berghain, it also hosts a queer sex club, dark spaces and bars, while the plant’s former boiler room, the Halle am Berghain, with its columns and suspended coal chutes, has currently been taken over by the LAS Art Foundation to stage a number of exhibitions, including Huyghe’s Liminals.

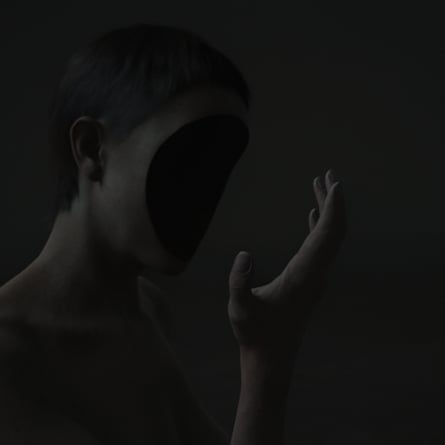

Light comes and goes on the screen, never quite enough to let you sense the volume of the space you have entered. Distances are hard to gauge. A delicate hand emerges on the screen, not quite in colour, not quite in black and white. There’s a body here that’s almost human, in a bleak, desiccated landscape utterly devoid of life. It might as well be Mars. A female face with short cropped hair appears: except there is no face, just a yawning dark cavity scooped out between chin and brow. This is more than disconcerting. Suddenly everything tilts and there’s a roaring, flickering abyss opening up, and we see the same figure tiny and distant on the rim of an even greater, all-consuming void. Globs of light turn in space and are gone again. There is a great deal of aural and visual interference and everything hangs for a moment on the brink of total collapse. These anomalies and glitches in space and time are to do with Huyghe’s engagement with quantum mechanics, and the conversations he has been having, through the LAS Foundation, with physicists and philosophers. Artists often read or misread philosophy or science – whether it is Martin Heidegger or Werner Heisenberg – as if it were poetry, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

Watching Huyghe’s more or less human character navigate an entirely indifferent world is a painful experience. They seem all too human, as the camera homes in on their dirty hands and mottled skin, their cuts and grazes, their breasts and a caesarean scar, their vulnerable nakedness, made somehow more awkward and unsettling by being coded female. Sometimes going on hands and knees, sometimes walking purposefully, sometimes as inert on the ground as a beached fish, sometimes furrowing the ground with their head, or hitting their forehead against the earth, sometimes sitting and contemplating their hands with the eyes they don’t have; the sounds of scurrying and crawling, of granular sifting and the displacement of small stones make the whole thing both believable and extremely abject. Is this a person or an avatar? At one point they approach a gnarly outcrop of rock and penetrate the void in their head with it, moving back and forth, a cyclical, rhythmic motion that is both bizarre and awful to watch. Is this to do with Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle? Search me. At another point the figure’s hands become unnaturally malleable, their fingers curling and twisting the wrong way and becoming peculiarly attenuated.

The camera dwells on shapes in the rocks, on shadows and silhouettes. I see a human profile here, a pair of lips and a whole face there, accidental gargoyles staring back, not unlike Willem de Kooning’s sculptures, or Francis Bacon’s painted heads. Seeking out expressions, we project them on to the inanimate. Something else shimmers in the murk, but it is less likely gold than a turd. I also thought of Samuel Beckett’s How It Is, and of endlessly crawling through mud, and good old-fashioned existential dread. Speaking with Huyghe after spending an hour in Liminals, he said it was good to take one step towards cliche, but never two.

So much of this new work relates to earlier sculptures and films by the French artist. I thought of the macaque monkey, dressed as a waitress and wearing a female, human mask in his 2014 film Untitled (Human Mask), set in an abandoned restaurant near the Fukushima nuclear exclusion zone, and the concrete replica of a 19th-century reclining nude sculpture by Max Weber, with its head encased in a live beehive, as part of Huyghe’s Untilled at Documenta 13 in 2012.

What’s on the screen and what’s happening in the space around me get confused. What is happening in the here-and-now of Liminals relates back to Huyghe’s earlier work, an entire world becoming more rounded with each new work. This is deliberate on Huyghe’s part. For all the talk of quantum mechanics, of the collapse of the wave form, of waves and particles (which is how we’ve always been thinking about light) what seems to me to matter here is a kind of porousness, between past and present, things and images, insides and outsides. One of the reasons the artist wanted to show at Berghain was to echo the activities elsewhere in the building, the bodies dancing, people desiring and craving and losing themselves in music and in sex, in spaces that are both limitless and bounded. Liminals has lodged in my head, and won’t go away. How alive it all is, how unhinging.

3 days ago

18

3 days ago

18