Over the course of three decades, Sara Banerji, who has died aged 93, wrote 10 novels combining realistic domestic detail with myth and magic, and sudden violence with a quirky humour. In the first, Cobweb Walking (1986), the child Morgan is able to walk on cobwebs: Sara’s storytelling made the surreal real, bringing a fresh voice to fiction by interweaving fantasy with the absurdities of everyday life.

The absence of a father is a theme in several of the novels, her own British army veteran father having died during her teens. In Cobweb Walking, Morgan loses her widowed father to another woman. Fatherless Alice is central in the blackly comic Shining Agnes (1990). In Absolute Hush (1991), the pubescent, unpredictable twins George and Sissy and their beautiful mother live in a grand moated house next to an army camp, their father missing in action, with incest, infidelity and comedy combining in a heady, surprising mix.

The Observer found it to be “a bold, fantastical work … an extraordinary marriage of pyrotechnics and grace”. Other reviewers compared her wit to that of Evelyn Waugh and Muriel Spark.

Sara’s marriage to Ranjit Banerji in 1957 led to India providing the setting and inspiration for several of her books. In The Wedding of Jayanthi Mandel (1987), Police Deputy Babu relates the memorable – and often violent – events of the wedding day in a tone of astonished bemusement. The Tea-Planter’s Daughter (1988), narrated partly by the servants in a post-colonial household, shows repression and desire in the south Indian hills, and Shining Hero (2002) uses Hindu mythology and epic poetry as a template for a contemporary novel of sibling rivalry. Her final novel, Tikkippala (2015), deploys magical realism to tell the story of a 20th-century rajah’s family.

Born in Stoke Poges, in Buckinghamshire, Sara was one of four children of Anita (nee Feilding), a descendant of Henry Fielding who herself wrote novels as Anne Marie Fielding, and Sir Basil Mostyn, a baronet and army officer who had served in the second world war in the North Africa campaign, including the Battle of Alamein.

While he was away as a lieutenant with the Royal Army Service Corps, Sara, her mother and siblings stayed at Beckley Park, a Tudor house near Oxford owned by her uncle, Basil Feilding. Its moat and topiary-filled garden provided the social setting for several novels.

After the war her father took the family to live on a tobacco farm in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), where their home consisted of two mud huts with no water or sanitation. The marriage broke down, and the children returned to Britain with their mother; they saw little of their father before his death in 1956.

The family settled near Oxford, taking in lodgers to pay the bills. Anita had connections in Europe, and set up the Mostyn Bureau, an agency for au pairs. Sara hitch-hiked round Europe and au paired in Paris and Vienna. On her return she met Ranjit, a recent Oxford graduate, in the coffee bar where she was working. She soon proposed to him, but Ranjit refused, claiming his family expected him to marry a Brahmin girl. Sara, whose family wanted her to marry a well-born Englishman, persisted, the two families relented, and they were married in Munnar, Kerala, where Ranjit had a job in the tea industry.

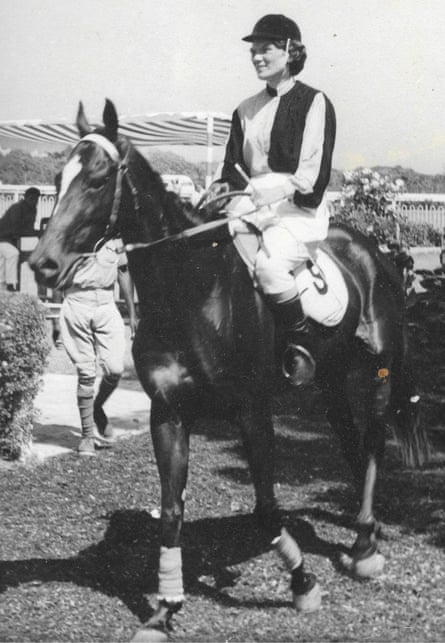

During their 16 years in the country, initially in Munnar, then near Calcutta (now Kolkata), where they had a dairy farm, Sara wrote, painted and taught art, exhibiting her paintings in Madras (now Chennai) and Delhi. She also became a successful amateur jockey – timing the births of their three daughters so that they did not coincide with the Flat racing season.

The radical leftwing Naxalite insurgency, prompted by dissatisfaction over poverty and land ownership, caused their dairy farm to fail, and in 1973 they left India with £10, the maximum amount they were allowed to take out.

Sara and Ranjit found work where they could, first in Bedfordshire and then Sussex, where Sara set up Henfield Lady Gardeners. Among her clients was the bestselling horror writer James Herbert, whose success increased Sara’s determination to become a published novelist. I was fortunate to be her editor at Victor Gollancz for her first six books.

In 1996, the family moved to Oxford to look after Sara’s ageing mother, and she taught creative writing at a continuing education college until 2014. She also set up a creative writing group, which she ran until early 2025.

Sara never stopped creating: she painted, sculpted and wrote to the end, including a memoir of her childhood for the family.

Her brother Jeremy died in 1988 and Ranjit in 2022. She is survived by their three daughters, Bijoya, Sabita and Juthika, five grandchildren, Anna, Rory, Maia, Chandi and Sumi, four great-grandchildren and her siblings, Trevor and Joanna.

1 month ago

108

1 month ago

108