For a nightclub that existed for less than 18 months, the Blitz – which opened at 4 Great Queen Street in Covent Garden, London, in February 1979 and closed in October 1980 – had an outside influence on UK culture.

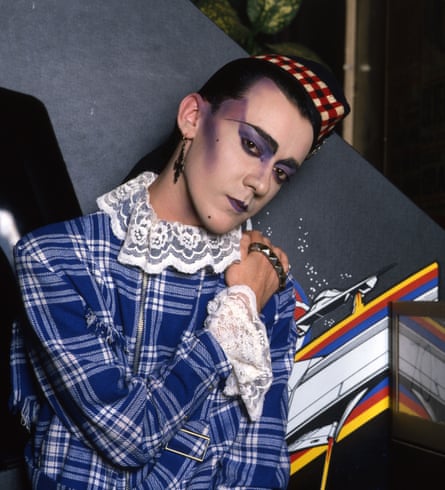

Set up by scenester Rusty Egan and aspiring pop star Steve Strange, who went on to have a Top 10 hit, Fade to Grey, with his band Visage, the Tuesday night party in a 200-person capacity space swiftly became the place to be seen if you were young, cool or creative. Famously, it spawned era-defining pop stars including Spandau Ballet, Sade and Boy George. Equally, though, fashion was central to its success.

A new exhibition at the Design Museum, Blitz: the Club That Shaped the 80s, attempts to unpack its cultural and sartorial history, featuring clothing, photography, magazines and even an Instagram-friendly recreation of the bar complete with beer bottles and a projection of Egan “playing” music.

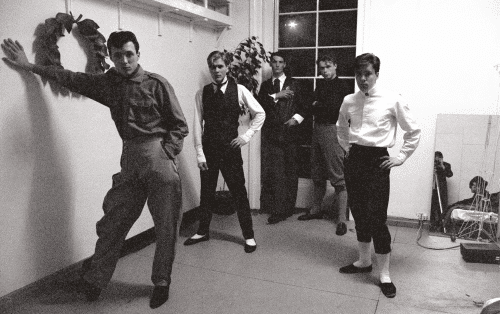

The exhibition includes items made by regulars such as the fashion designer Stephen Linard, who worked with David Bowie and Boy George, milliner Stephen Jones, BodyMap’s David Holah and Stevie Stewart, and Darla Jane Gilroy, who featured in the 1980 video for Bowie’s Ashes to Ashes. It also showcases the sometimes breathtaking creativity of the clubbers’ outfits. The experimentation led to them mixing 1940s tailoring with theatrical costumes, charity shop finds, full faces of makeup and hair that defied gravity. In a video shown in the exhibition, one club-goer describes how it takes three hours for her to get ready to go out.

The objects included here – from club flyers to record covers and early editions of magazines such as i-D and the Face – are worth examining. But it’s the images of the so-called Blitz kids that most convincingly display the moment in time. A wall of photographs features the artist Duggie Fields in a 40s printed suit and quiff; two club-goers with makeup to resemble women in Picasso’s blue period; a woman dressed as Queen Elizabeth I; Linard in a lace ruff and pillbox hat and a man encased in clingfilm smoking a cigarette. Bowie, pictured in a leather shirt pouring a beer, looks relatively pedestrian by contrast.

At a preview of the exhibition, the curator, Danielle Thom, said the time these young people were living in was part of why the looks were so experimental. “Fashion provided an element of escapism,” she said. “It’s the tail end of the winter of discontent, Thatcher has been elected … although, for the most part, they didn’t see themselves as especially political in the sense of being politically active, they were undoubtedly influenced by the political context of the day – rising unemployment, literally bin bags piled high in the streets.”

Punk – although on its way out by 1979 – was essential to how the Blitz kids’ look developed. “In terms of their ethos and their work, the spirit of punk very much carried on – the idea of DIY and a disregard for existing hierarchies of taste,” says Thom. The young people who went to the Blitz often lived in squats, and rejected a 9-5 lifestyle. “[But] the visuals of punk, the predilection for deliberately offensive imagery, the deliberate ugliness as a provocation, that was consciously rejected by embracing elegance and a degree of romance.” Thom argues that, much like the music and graphic design of the time, the fashion was “quite postmodern – picking and choosing from the past to create something new”.

If the scene itself was tiny, Blitz soon loomed large in the media, thanks to Strange. “He was very proactive,” says Thom. “He would ring up journalists and say: ‘I’ve got this club night. You must come and have a look.’” As a lot of the TV footage and newspaper clips included in the exhibition show, the coverage was more likely to show alarm at the outfits than be in favour of them. Even so, Strange’s strategy worked – there were soon queues to get in on Tuesday night.

Fashion, again, was central to policing this new popularity. “A lot has been made of the exclusivity, that you could only come in if you looked right. But that exclusivity was as much a safety strategy as it was about creating mystique,” says Thom. “Blitz wasn’t explicitly a gay club in the sense that Heaven might be, but it was a club in which many of the regular attendees were gay, were queer, were exploring their sexual identities.” Fashion allowed Strange – who stood at the door and decided who was allowed in – to protect his clientele. “This is London in 1980, not exactly a tolerant time or place,” says Thom. “Inside Blitz was a safe space – to use a contemporary term.”

after newsletter promotion

This exhibition is the latest in a series exploring 80s club culture – from the Leigh Bowery retrospective at the Tate Modern to the National Portrait Gallery survey of the Face magazine and Outlaws at the Fashion and Textile Museum, which looked at the fashion designers who were part of this scene. Thom thinks this new interest is partly down to timing. “For people who weren’t there the first time, there’s novelty about just how analog everything was,” she says. “And for people in their 50s and 60s, it’s a hit of nostalgia.”

More poignantly, there is a wistful fascination. “You can argue that many of the conditions that made [80s club culture] possible are being eroded,” says Thom. “Nightclubs are closing at an alarming rate because of rising rents, university is once again the preserve of those who can afford it. Even something as simple as sourcing your secondhand clothing, it’s a highly professionalised vintage marketplace, it’s not nipping to a charity shop and finding an amazing bargain.”

Put in these terms, this exhibition is the latest in a series of shows that are about far more than outlandish outfits, hedonistic club kids and pop stars in their pomp. Says Thom: “I hope this serves as a warning as well as a love letter to the importance of club culture.”

3 months ago

92

3 months ago

92