Jonny Melton knew that his club night Nag Nag Nag had reached some kind of tipping point when he peered out of the DJ booth and spotted Cilla Black on the dancefloor. “I think that’s the only time I got really excited,” he laughs. “I was playing the Tobi Neumann remix of Khia’s My Neck, My Back, too – ‘my neck, my back, lick my pussy and my crack’ – and there was Cilla, grooving on down. You know, it’s not Bobby Gillespie or Gwen Stefani, it’s fucking Cilla Black. I’ve got no idea how she ended up there, but I’ve heard since that she was apparently a bit of a party animal.”

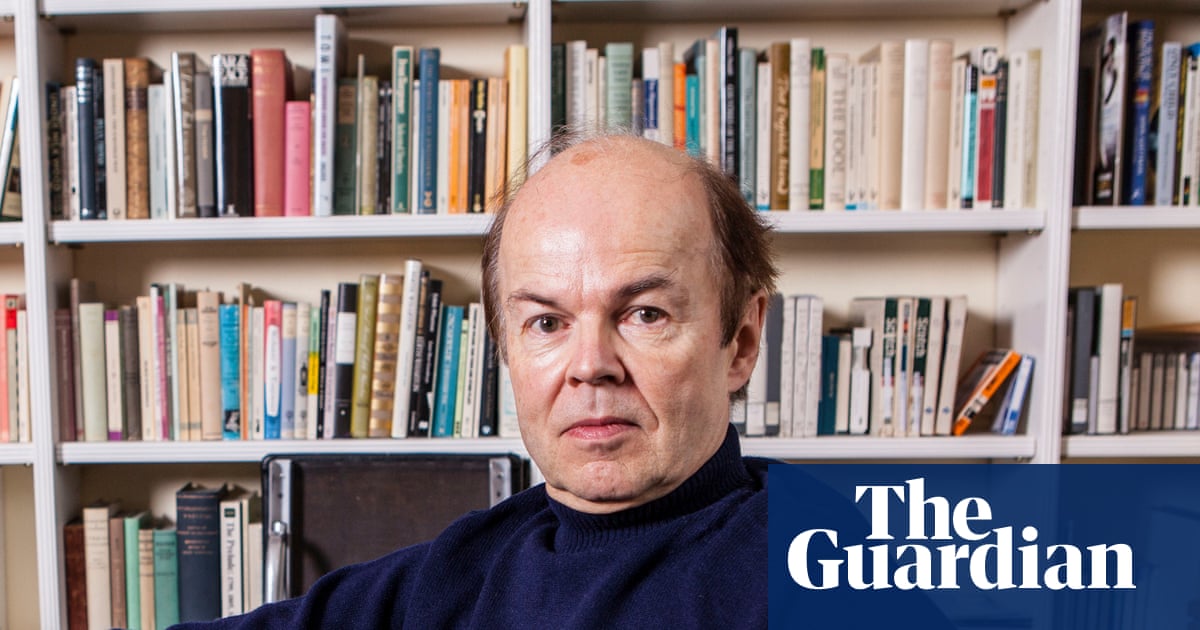

It seems fair to say that a visit from Our Cilla was not what Melton expected when he started Nag Nag Nag in London in 2002. A former member of 80s goth band Specimen who DJed under the name Jonny Slut, he’d been inspired by a fresh wave of electronic music synchronously appearing in different locations around the world. Germany had feminist collective Chicks on Speed and DJ Hell with his groundbreaking label International DeeJay Gigolos. France produced Miss Kittin and The Hacker, Vitalic and Electrosexual. Britain spawned icy electro-pop quartet Ladytron and noisy, sex-obsessed trio Add N To (X). Canada spawned Tiga and Merrill Nisker, who abandoned the alt-rock sound of her debut album Fancypants Hoodlum and, with the aid of a Roland MC-505 “groovebox”, reinvented herself as Peaches. New York had performance art inspired duo Fischerspooner and a collection of artists centred around DJ and producer Larry Tee, who gave the sound a name: electroclash.

The lyrics tended to be witty, occasionally foul-mouthed and very camp. The sound had house music, techno, 80s synth-pop and electro in its DNA, but boasted a rough-hewn, punky edge, the latter partly down to attitude and partly down to the era’s technological advances. “It isn’t like today, where you can take an idea to a playable version in five hours on a laptop,” says Larry Tee, “but you could record something releasable in your bedroom, you could get a Juno 106 [synthesizer] and alter the sounds and fry and burn them. I’m convinced the best electroclash tracks happened because people made mistakes, the levels were too loud or there was something wrong.”

It was audibly a reaction to something. In Britain, it felt a world apart from the increasingly slick dance scene of superclubs and superstar DJs. In New York, Larry Tee suggests it was a shift away from “trance and tribal house”. For Peaches, who had recorded her 2000 album The Teaches of Peaches in her bedroom, “lying in bed, smoking weed, masturbating and making beats”, it was music made by “marginalised, queer people … who were fed up with a system that was telling us ‘rock music has to be by four beautiful boys down the line from the Rolling Stones, electronic music has to be completely serious like you’re doing brain surgery while turning buttons’. Where was the punk? And for me, I can’t think of another time in music history where women were so at the forefront – Chicks on Speed, Miss Kittin, Tracy + the Plastics. It’s always like, ‘This dude did this’, you know?”

Whatever it was an answer to – superclubs or rock’s traditional patriarchy – electroclash seemed to find an audience quickly. It wasn’t the only music Melton and his fellow DJs played at Nag Nag Nag – as underlined by a new 5CD box set, When the 2000s Clashed, they were equally wont to drop old punk singles, early industrial music or the Neptunes’ exploratory R&B – but electroclash was the club’s sonic backbone, and the night was an immediate success. Boosted by approving reviews first in the gay press, then the style magazines, its initial clientele – “a few old goths and some art students in their mum’s old curtains,” according to Melton – were soon joined by a succession of celebrities: Kate Moss, Alexander McQueen, Pet Shop Boys, Boy George, Björk. Perhaps inevitably, it attracted comparisons to celebrated New Romantic hangout the Blitz. “But there was no door policy, no guest list,” demurs Melton. “I didn’t want any of that exclusivity shit. It wasn’t posey at all, there was more a feeling of abandon. It was very hedonistic.”

“It was the epitome of amazingness, this incredible melting pot of every kind of character,” says Concetta Kirschner, better known as rapper Princess Superstar, who turned up at Nag Nag Nag while promoting her 2002 UK hit Bad Babysitter. The club had an immediate impact on her sound. “It gave me a shot of freedom. I felt like there were a lot of tightly defined rules in hip-hop. But after Nag Nag Nag, I felt I could experiment, be whatever I wanted, rap over dance music or crazy new rhythms.”

The newly electroclash-adjacent Princess Superstar had a Top 3 hit with Perfect (Exceeder), a collaboration with Dutch producer Mason, but it was the exception that proved the rule. For all the excitement and press coverage it generated, electroclash noticeably failed to produce a major crossover star, although it wasn’t for want of trying in some quarters. The Ministry of Sound’s record label famously spent vast sums signing New York duo Fischerspooner, but their debut album #1 failed to catch light. “Electroclash didn’t work in hygienic conditions,” offers Mark Wood, a DJ and Nag regular behind the new box set. “It worked in clubs that were dark, hot, grubby, full of smoke, all sorts of things going on.”

Peaches, meanwhile, went out on tour as a support to hard rock artists, including Marilyn Manson and Queens of the Stone Age: their audiences, she says, were “horrified”. “I think a lot of [electroclash artists] were offered these more traditional tours and thought ‘I can’t handle it’. On the Marilyn Manson tour I was spat on every night, but I rapidly developed some prank skills and some great one-liners.”

But in Britain at least, electroclash entered the mainstream regardless, audibly impacting on the way existing pop stars sounded. Sugababes rebooted their career with Freak Like Me, a Richard X-produced reimagining of the old Adina Howard hit backed by the music from Tubeway Army’s Are Friends Electric? Another Richard X mashup, Being Nobody, which melded Rufus and Chaka Khan’s Ain’t Nobody with the Human League’s Being Boiled, was a Top 3 hit for Popstars runners-up Liberty X. You could hear echoes of electroclash in Goldfrapp’s platinum-selling 2003 album Black Cherry, Rachel Stevens’ 2004 hit Some Girls and Madonna’s 2005 album Confessions on a Dance Floor. Even Fischerspooner ended up on Top of the Pops, in the company of Kylie Minogue, performing their remix of Come Into My World.

In America, however, the movement provoked a backlash. “It was unfairly beaten up after three or four years,” says Larry Tee. “Electroclash was girls, gays and theys, the music industry didn’t really invest in those three categories, and I think they were as anxious to kill it as they were disco. I think the reason they wanted to burn electroclash so fast is that it didn’t really include that soccer bro culture, which EDM did.”

Nag Nag Nag eventually closed its doors in 2008 – the club that hosted it, Ghetto, was demolished to make way for the Crossrail development. It seemed symbolic of the end of something bigger than electroclash. “It was Soho’s last stand as a grubby nightclub place – that’s all literally gone, everything moved east,” says Wood. “It was around the same time that smartphones arrived, which changed everything too. All that happened around the same time electroclash was being put to bed. Nothing lasts for ever if it’s worth having in pop music.”

But recently, Jonny Melton noticed something odd. He was being sent new dance tracks that self-described as electroclash, while club nights, including London’s Shackled By Lust and Bloghouse, also use the term to describe what’s on offer. “That would never have happened before,” he laughs. “At the time electroclash was like goth – no one who was in a goth a band would ever admit to being a goth band.”

Meanwhile, in 2023, Peaches embarked on a tour performing her debut album: it was both rapturously received and attracted an audience noticeably big on twentysomethings too young to remember its release. Princess Superstar, whose “career sort of died” in the 2010s, has watched with baffled delight as her electroclash-era hits unexpectedly enjoyed a new lease of life. First, Perfect (Exceeder) belatedly went gold in the US after it was used on the soundtrack of the 2023 movie Saltburn. Then, last year, her 2008 collaboration with Larry Tee, Licky, unexpectedly went viral on TikTok. “I think they thought it was by Britney Spears,” she says. “So I put a video up like, ‘Hey dudes’ and it all went crazy.”

She’s currently making new music, some of it in collaboration with Frost Children, a US duo among a wave of younger artists who bear the influence of electroclash: you can hear its strains in Snow Strippers, Confidence Man and the Dare. Larry Tee, who’s currently planning an electroclash documentary, suggests there’s an influence in the music of both Lady Gaga and Charli xcx’s Brat.

The music on When the 2000s Clashed still sounds remarkably fresh. Perhaps that fact that most of it remained underground, never dominating the singles chart or the radio playlists helped; so too does the fact that it’s informed by a lot of ideas that were subsequently mainstreamed: it was gender fluid before anyone talked about gender fluidity, sex-positive before anyone used that term either. “I think the younger generation get it,” nods Larry Tee, “because it was like the resistance: we’ve had enough of homophobia, enough of misogyny. For a moment, the door was open.”

1 month ago

53

1 month ago

53