Although he was a major modernist artist whose collaborators ranged from European greats like Pablo Picasso and André Breton to new world giants like Aimé Césaire, Cuban artist Wifredo Lam has not seen a major US retrospective worthy of his stature. That changes with the MoMA’s blockbuster show Wifredo Lam: When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream.

The product of years of work and dozens of collaborations with institutions and collectors around the world, When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream shows the entire sweep of a career that straddled eras. Lam is best-known for agglomerations of elongated and mysterious figures that borrow from cubism and surrealism, although the exhibition also shows different sides of this artist: lushly colored and textured pieces that verge on abstraction, sculptural heads that point toward the artist’s African roots, early figurative works, and the weird cacophonies of forms that the artist made through the 1960s and 70s.

“He knew that what he was doing may not have been understandable to the people of the street of even his peers, but that a true picture has the power of the imagination to work, and it just might take a little time,” said Beverly Adams, a curator with the MoMA who organized When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream alongside MoMA director Christophe Cherix. “He knew what he was going was hard and important and would have relevance long beyond his time.”

Following a major European 2015 retrospective that touched down at the Pompidieu, the Tate, and the Reina Sofía, New York’s MoMA was determined to offer a suitably large retrospective of Lam in the United States. Cherix and Adams knew that this would be a massive undertaking, as well as one that would require a great deal of persistence and ingenuity.

According to Adams, all of this hard work was in service of opening dialogues that could only come from bringing together so much of Lam’s creative output. “There have been smaller scale shows, but never really any institution that’s taken on the complexity, logistically of a show this size,” she said. “We traveled all over to see as many things as we could, and we were able to get loans of things that we dreamed of but weren’t sure we could get, things that have been hidden in private collections for decades and decades and that needed to come back out into the public. It’s important to see these things alongside together. We wanted to have those dialogues between those works.”

The MoMA has a long history with Lam, beginning with his Mother and Child in 1939, the first Lam work to be acquired by any institution in the world. “It’s a very simple, hieratic portrait of a woman holding a child,” said Cherix. “It feels like it’s both grief and tenderness at once. It relates to his personal story of losing a wife and child to tuberculosis in Spain in the early 1930s, but it also has this degree of tenderness that makes it feel like a universal portrait that could include anybody.”

From there, the MoMA would go on to acquire Lam’s unquestioned masterpiece The Jungle in 1945. Measuring over 7ft on each side, the massive oil and charcoal work blends together pieces of human bodies, along with jungle trees, animals, and other aspects of the landscape into a work that feels almost limitless in its complex web of interconnections. It has become known as a major example of the cross-fertilization between the major artistic currents of cubism and surrealism then dominating Europe with the colonial realities that African-Caribbean individuals such as Lam would have been forced to live under.

“You can see the amazing thing he was doing in Marseille, with Breton and the other surrealists,” said Adams, “you can really see all these bits and pieces coming together. You can see Cuba in this neo-colonial state, a country run on sugar and tourism, where issues of race, inequality, and the colonial legacy are still very visible. It gathers his time in Europe with his return to Cuba.”

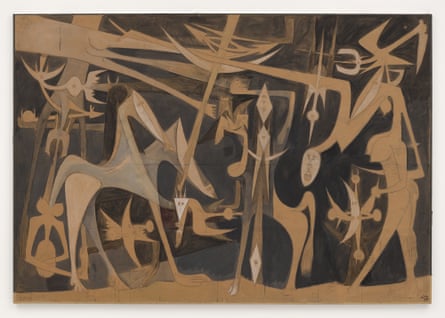

Another major and rarely seen piece included in this show is the aptly titled Grande Composition, Lam’s largest work, which had spent decades residing in a Paris apartment building of all places. The piece had long been in the holdings of a Belgian art collector before finding its way to Paris, which, due to its enormous 14ft-by-9ft size, seemed destined to be its final resting place.

“It was high on our list,” said Cherix. “We were able after a few attempts to see the work, and we found it absolutely essential. That started a long conversation that took a couple of years, we had to convince a collector that we could ship it to NY safely. We knew that the MoMA would be one of the few places that could preserve it for future generations.”

One of the major points of including Grande Composition, made in 1949, is to remind audiences that Lam had a flourishing career after the high watermark of Jungle. In fact, Lam would go on creating right up to his death in 1982, including a series of etchings and poems released in collaboration with Césaire.

“Grande Composition was so important to us to show that there was an after Jungle,” said Cherix. “Lam remained so critical in the decade that came afterwards.”

Although the MoMA was unable to secure any loans from the National Museum of Fine Arts in Havana, a major holder of about 200 works by Lam, there was much cross-fertilization between the institutions, including bringing Cuban scholars to New York to see The Jungle. “It was very moving seeing Cuban scholars who had studied Lam for virtually their whole lives, seeing The Jungle for the first time ever in person,” said Cherix.

And to hear the way that Cherix and Adams talk about Lam, the MoMA sounds almost certain to do another show, possibly one that will eventually include works currently in Cuba. “An exhibition is always one step further, but there’s a lot to be done on Lam,” said Cherix. “There’s so much that remains to be done. We’re really looking forward to people finally having access to a large body of his work.”

“He’s truly a model of the transnational artist,” added Adams. “Maybe we didn’t have the vocabulary to think about that before. He was shoehorned into categories that didn’t really fit, but we are trying to crack open the conversation wider.”

-

Wifredo Lam: When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream is on display at the Museum of Modern Art in New York from 10 November to 11 April

1 month ago

39

1 month ago

39