Dr Paul E Mullen and his family were living near Dunedin, New Zealand when, one evening in November 1990, they heard gunfire. The shots continued into the night, followed by the distant sound of police and ambulances. At 9pm, a hospital colleague told him that a few kilometres away, in Aramoana, someone with a gun had started shooting.

As it turned out, Mullen had heard of the perpetrator before; one of his long-term patients was the man’s nextdoor neighbour, and soon Mullen would learn that many other people he knew had been injured or killed.

“I’d never really thought about these things,” Mullen tells the Guardian. “They had never been on my radar.”

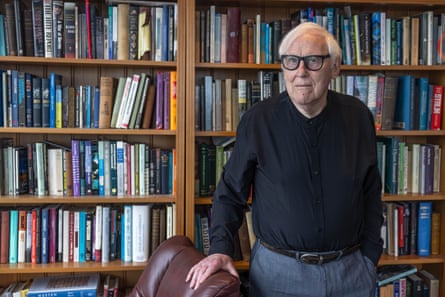

The Bristol-born Mullen had always dabbled in forensic work, but the events at Aramoana piqued his curiosity. He would soon pivot to become a full-time forensic psychiatrist, specialising in some of the gravest acts known to society, from stalking and child sexual abuse to mass killings.

Speaking over the phone from his home in Melbourne, the 81-year-old has the spry, genial air of any ordinary semi-retired professional – but his career trajectory has brought him face-to-face with men whose violent crimes once brought them international notoriety.

Perhaps the most striking encounter came just a few years after Aramoana, when in April 1996 news broke of an even deadlier attack in Port Arthur, Tasmania. By then Mullen was in Australia, working as professor of forensic psychiatry at Monash University. He received a call summoning him to Royal Hobart hospital where this latest perpetrator – whose name Mullen refuses to use – had been taken alive hours earlier after shooting 55 people, killing 35.

“That was my first experience of actually spending time with one of these killers and beginning to find out something about them,” Mullen recalls.

The 28-year-old was being treated for burns, having set fire to a guesthouse in a final confrontation with police. At the hospital, cautious authorities had cleared the floor and strapped him to the bed.

At first, Mullen thought the blond-haired young man seemed frightened, and he saw no reason to be afraid for his own safety. While the television crews and journalists swarming outside were describing him in terms like “evil”, “unholy”, and “monster”, Mullen approached the young man not as a “killer”, but a “person who has killed”. He sought to build a rapport with his subject, even seeking to have his restraints removed.

“I thought it was going very well, until suddenly, blam, he says: ‘I’ve got the record, haven’t I?’”

Mullen was taken aback. “But you’ve just got to carry on,” he recalls, pausing for a moment to gather his thoughts. “You’ve got a job to do.”

While the Port Arthur killer angrily rejected Mullen’s suggestion his actions might have been inspired by another high-profile attack a month earlier in Dunblane, Scotland, Mullen says he soon started to talk about other massacres.

“So he did know quite a lot about these previous killers,” Mullen reflects. “And this is typical.”

The following decades would see Mullen interview many men in a similar position to the perpetrators of Aramoana and Port Arthur, as he became a leading authority in what are often referred to as “lone-actor mass killers”. But despite the implication of solitude, the man in that Hobart hospital ward revealed what would become a common thread in all of Mullen’s dealings with lone mass killers: they are rarely acting in isolation.

Today, Mullen reflects on the complex factors that have fed an alarming rise in such events over the past half-century – Texas university in 1966, Port Arthur, Norway’s Utøya island in 2011, Las Vegas in 2017, and Christchurch in 2019 to name just a few – at a scale and regularity that seemed unimaginable not long ago. One of the strongest, he says, is the emergence of a “cultural script”, a conclusion shaped not only by his own first-hand experience, but the history books.

“The first time it’s ever happened in the western world was in Germany, 1913.”

In September 1913, a schoolteacher killed his wife and four children before travelling to Mühlhausen armed with several guns and hundreds of rounds of ammunition. He began indiscriminately shooting, killing nine people before he was apprehended – but it’s what happened next that Mullen finds telling. “He had no influence – between 1913 and 1966 there were three incidents, one was actually in Melbourne. But there was no cultural script created.”

Things changed, Mullen says, after a shooting in Austin, Texas in August 1966, when a 25-year-old male student climbed to the 28th-floor observation deck of a University of Texas building and opened fire, killing 15 and injuring another 30.

“He was in every major newspaper in America, on the front page the next day with his photograph and his name, and he was covered worldwide over the next few days – they later made a film,” he says, referring to 1975’s The Deadly Tower, starring Kurt Russell as the red bandana-clad gunman.

“It was the Texas university tower massacre that created the script, which has now grown and grown and grown,” Mullen reflects. “And the first imitator of the Texas killer was only five weeks [later].”

Like the Port Arthur killer, these are often friendless men fuelled by a mix of resentment and a sense of weakness, drawn to the promise of infamy, publicity, and a noteworthy death enjoyed by previous mass killers. Some even dress like their predecessors, from Russell’s red bandana to the all-black attire of the teenage Columbine school shooters.

“They gather grievances, grievances, grievances,” Mullen says, echoing the common complaints he has heard across his career. “‘People mistreated me’; ‘I was cheated’; ‘they’re not fair’; ‘no one likes me’. All these things, but they also feel that they should have fought back.

after newsletter promotion

“The resentment builds up and builds up, and it becomes your whole attitude to the world, which is angry, which is full of a sense of grievance. But it’s much worse, because you never did anything. And this, in a sense, is your final reply.”

In his new book, Running Amok: Inside the Mind of the Lone Mass Killer, Mullen unpacks these cases alongside other similar stories.

“What emerges is the big story, what this is about, how it developed, how we can do something – not to stop it completely, but to reduce it,” he says. Along the way Mullen studiously avoids naming any modern perpetrators, instead centring the names and lives of their victims and says refusing to name killers is the “quickest, cheapest and easiest way we can cut down this escalating rate of killings”. He also warns against using terms like “lone wolf”.

“This is exactly what they want to be seen as – the lone wolf, the predator going around the edges,” Mullen says. “They’re not wolves. I mean, they’re sheep.”

Similarly, police and media can thwart their ambitions by trying to capture perpetrators alive, avoiding reporting details of their lives and manifestos, and not allowing them to use a courtroom as a platform.

He acknowledges that public safety needs to be carefully balanced with due process, transparency, and a free press. Today, authorities must also contend with an attention-driven media landscape and the vast, unregulated internet increasingly hooked on sensationalised true crime.

Ironically, Mullen says he initially struggled to find a publisher for his more nuanced approach to the subject. Some agents and publishers said he lacked a “profile”, for which he had a good reason: his proximity to so many mass killers over the years – from Aramoana, to Port Arthur, to Hoddle Street in Melbourne – has drawn suspicion from the conspiracy-minded. One conspiracy theory website dubbed him “Mysterious Mullen from Monash”.

“How did I discover it? Death threats,” he says. “My personal assistant at the time had a little drawer for death threats, filled up. [So] being a little anonymous helped.”

As for his own personal feelings about a career spent coming face to face with those who have committed unthinkable acts?

“I mean, they’re people,” Mullen reflects. “My job is to understand why they’ve done something extraordinary. Understanding doesn’t mean forgiving. Understanding doesn’t mean it’s OK – ‘I understand, now you can toddle off’.”

Mullen’s encounters reveal that, rather than embodying a “shameful, utterly wicked criminality”, these crimes are often the convergence of predictable patterns and cultural scripts that can be interrupted before ending in tragedy.

“These people are uncertain whether they’re going to do it up to the last moments,” he says. “One tossed a coin. The Tasmanian killer stopped at a cafe because his biggest grievance was that no one would ever talk to him. And there were two girls there, and he thought, ‘Well, if, if I go over there and talk to them, if they talk to me back, I won’t do it.’

“I’m curious,” Mullen reflects. “They’re human beings. I want to know the answers to why they did things, and those answers hopefully will be helpful in preventing it in other people – and hopefully, maybe of some use in saving them.”

-

Running Amok: Inside the Mind of the Lone Mass Killer by Paul E Mullen is out now through Extraordinary Books

1 month ago

77

1 month ago

77